THE WAGES OF U.S. OVERCOMMITMENT

The demands placed by Allied Force on U.S. equipment and personnel underscored the extent to which the U.S. defense posture has been stretched dangerously thin by the post–cold war force drawdown and concurrent quadrupling of deployment commitments worldwide. During the initial post–cold war decade of the 1990s, the U.S. active‑duty force in all services shrank by 800,000 personnel to 1.4 million, a reduction of more than one‑third. The Army was cut from 18 to 10 active divisions, the Navy diminished in size from 567 ships to just over 230, and the Air Force lost half of its 24 fighter wings. Yet during that same period, the U.S. armed forces were tasked with 48 major deployment missions overseas, in contrast with only 15 between the time of the U.S. exit from Vietnam and the collapse of the Soviet Union nearly two decades later.[374]

The first practical effect of this drawdown manifested during Allied Force was the unexpectedly high rate at which scarce and expensive consumables were being expended to meet the air war’s demands. After only the first week, the Air Force found itself running low on CALCMs, with the initial stock of 150 down to fewer than 100.[375]The Air Force had had preexisting plans in hand to convert 92 additional nuclear‑configured ALCMs to CALCMs, but that process was expected to take more than a year. JDAM was still being tested at the time it was committed to combat. As of April 20, less than a month into Allied Force, there were only 609 JDAM kits remaining in stock.[376]The burdens placed by the air war’s demands on materiel of all kinds prompted a rising groundswell of military complaints that the results of seven years of underfunding were finally making their impact fully felt.[377]

On that point, a memorandum from Air Combat Command (ACC) to the Air Staff in late March frankly admitted that “our operational units are suffering, with few serviceable engines [and] depleted wartime spare kits.”[378]ACC’s commander, General Hawley, reported a month later that five weeks of bombing had left U.S. munitions stocks, notably CALCM and JDAM, in critically short supply, adding that “it’s going to be really touch‑and‑go as to whether we’ll go Winchester [the pilot’s term for running out of ammunition] on JDAMs.” Hawley warned that should a more serious crisis erupt elsewhere, ACC would be “hard‑pressed to give them everything that they would probably ask for. There would be some compromises made.”[379]The later resort to an increased use of dumb bombs in Allied Force was driven in part by the steady depletion of stocks of precision munitions of all kinds.

Seeking an explanation for this increased stress on the U.S. defense establishment across the board, General Hawley laid the blame squarely on the nation’s military overcommitment: “I would argue that we cannot continue to accumulate contingencies. At some point you’ve got to figure out how to get out of something.” Hawley added that because of a fourfold spike in the number of deployments in the 1990s at the same time the force was undergoing a reduction by half, “we are going to be in desperate need, in my command, of a significant retrenchment in commitments for a significant period of time. I think we have a real problem facing us three, four, five months down the road in the readiness of the stateside units.”[380]Earlier during Allied Force, even before SACEUR’s twofold force increase request was approved, Hawley cautioned that because of the existing strain on the system, “if we deploy the additional forces that are under consideration, those strains will become more evident,” causing a “significant decline in the mission‑capable rates” of the remaining forces to as low as 50 percent or less for some aircraft types.[381]

A second indication of the extent to which the U.S. military had come to find itself strapped as a result of the force drawdown was the sharply increased personnel tempo that was set in motion by the air effort. In all, some 40 percent of the active‑duty U.S. Air Force was committed to Operation Allied Force and to the concurrent Operations Northern and Southern Watch over Iraq. That was roughly the same percentage of Air Force personnel that had been committed during Operation Desert Storm, when the total force was much larger. Among other things, as noted earlier in Chapter Three, the heightened personnel tempo obliged President Clinton to approve a Presidential Selected Reserve Call‑Up authorizing a summons of up to 33,102 selected reservists to active duty.[382]It further prompted the Air Force chief of staff, General Michael Ryan, to insist that the USAF needed a recovery time no less than that routinely granted to the Navy every time one of its carriers returns from a deployment. Ryan flatly declared that “we are not a two‑MTW [major theater war] Air Force in a lot of areas, and one of them is airlift.” That shortfall made for one of many reasons why the Air Force later insisted that it needs 90 days to reconstitute its forces between MTWs.[383]

Earlier, as Allied Force entered its second month, Ryan told reporters that “the U.S. Air Force is in a major theater war.” (He later amended that remark to indicate that he had meant to say that the Air Force’s commitment level included Operations Northern and Southern Watch over Iraq.)[384]In the eight years since Desert Storm, deployment demands on Air Force assets had never before exceeded the level of two AEFs of around 175 aircraft each. NATO’s air war for Kosovo, however, demanded four AEF‑equivalents’ worth of USAF assets. Then‑acting Secretary of the Air Force F. Whitten Peters declared that as a result, the AEF concept would need to be reexamined.[385]

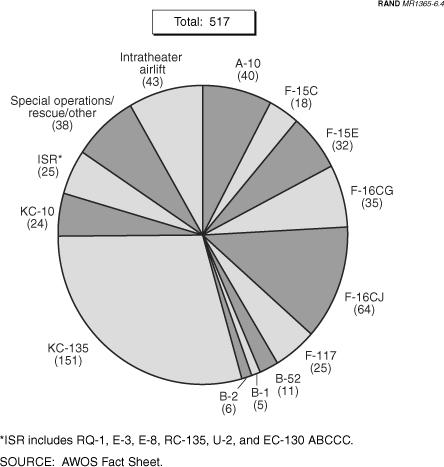

Third, the demands of Allied Force placed a severe strain on such low density/high demand (LD/HD) aircraft as Joint STARS, AWACS, the U‑2, the B‑2, the F‑16CJ, and the EA‑6B.[386]So many of these scarce assets were committed to the air effort that day‑to‑day training in home units suffered major shortfalls as a result. The most acute strains were felt in the areas of surveillance, SEAD, and combat search and rescue. Almost every Block 50 F‑16CJ in line service was committed to support SEAD operations, necessitating a virtual halt to mission employment training in the United States. (Figure 6.4 shows the overall USAF commitment to Allied Force, broken down by aircraft type.)

Similarly, Vice Admiral Daniel Murphy, the commander of the 6th Fleet, which provided the U.S. naval forces that were operating in the Adriatic, reported that there was an insufficiency of EA‑6B jammers and they, along with their aircrews, were being worn out by the air war’s demands.[387]Almost half of the initial batch of 11 EA‑6Bs used to spearhead the air operation had been drawn from assets previously committed to Operation Northern Watch at Incirlik Air Base, Turkey. Navy and Marine spokesmen declined to admit that their EA‑6Bs were being stressed to the danger point, but they did concede that they were being run ragged trying to marshal enough aircraft out of the total inventory of 124 to support the launching of Allied Force.[388]

Figure 6.4–USAF Aircraft Types Employed

An even greater demand was imposed on the Air Force’s various ISR platforms, which left none available for day‑to‑day continuation training once the needs of Allied Force were superimposed on preexisting commitments. During the time in question, the Air Force had only four operational E‑8 Joint STARS aircraft, two of which were committed to Allied Force (it has since acquired a fifth). As a result, the Joint STARS community found itself so stripped of its most skilled personnel that there was no instructor cadre left to work with new crewmembers who were undergoing conversion training. The low Joint STARS availability rate made for a typical Allied Force E‑8 mission length of more than 17 hours, with the longest missions lasting 21 hours. It took two or more inflight refuelings and backup pilots and crews to sustain each mission.[389]Some Joint STARS aircraft were flown at more than three times their normal use rates, creating a major maintenance and depot backlog that would take months to clear up. In all, U.S. LD/HD assets were stretched to their limit with tasking demands whose reverberations will continue to be felt for years in the areas of platforms, systems, reliability, parts, personnel, retention, and replacement costs. On this point, Admiral Ellis cautioned that the trend line is working in precisely the wrong direction–the demand for these assets in the future will only grow and they should be viewed as national assets requiring joint funding, irrespective of service, as the highest priority.[390]

Finally, Operation Allied Force exposed the extent to which U.S. forces are being stretched to the limit to support real‑world peacekeeping and peacemaking commitments on a routine basis, while also meeting the demands of engaging successfully in two simultaneous or near‑successive major theater wars. In the prevailing defense lexicon, Kosovo was supposed to be only a “smaller‑scale contingency.” Yet the number of U.S. aircraft committed to Allied Force quickly approached the level of a major theater war and exposed shortcomings in the availability of needed assets in all services. For example, the diversion of the USS Theodore Roosevelt from the Mediterranean to the Adriatic to support the air effort deprived U.S. Central Command of a vital operational asset. Likewise, the later redeployment of the USS Kitty Hawk from the Pacific to the Persian Gulf deprived U.S. Pacific Command of a carrier in the western Pacific for the first time since the end of World War II.

The Air Force was similarly forced to juggle scarce assets to handle the overlapping demands imposed by Kosovo, Iraq, and Korea. It positively scrambled to find enough tankers to support NATO mission needs in Allied Force. Ironically, both Kosovo and Iraq, in and of themselves, represented lesser contingencies whose accommodation was not supposed to impede the U.S. military’s ability to handle two major theater wars. Yet the burdens of both began to raise serious doubts as to whether the two‑MTW construct, at least at its current funding level, was realistic for U.S. needs. For example, when USEUCOM redeployed 10 F‑15s and 3 EA‑6Bs from Incirlik to support Clark’s requirements for Allied Force, it was forced to suspend its air patrols over northern Iraq immediately. Air patrols to enforce the no‑fly zone over southern Iraq were continued, but at a slower operational tempo. The net result was U.S. aircraft being flown two to three times more often than in normal peacetime operations.[391]

One example of the negative effects on combat readiness that surfaced during Allied Force was the frequent and widespread complaint by unit personnel in all services that their combat performance suffered because their lack of prior training opportunities with live weapons adversely affected their precision‑weapons employment techniques and procedures in actual combat. Indeed, the majority of American bomb‑droppers had never dropped a live LGB in training. That shortfall in combat proficiency was partly a reflection of limited range space, but it was also the result of under‑resourcing of combat units in the training‑munitions category. Numerous misses in Allied Force occurred because aircrews did not understand target‑area effects such as thermal bloom, smoke, and dust, which cannot be duplicated in peacetime training without live weapon drops. By one informed account, civilians were injured in Pristina and Surdulica as a direct result of smoke and IR bloom effects. Targets were also missed when aircrews discovered several surprising effects in the LANTIRN system when using the combat laser in the presence of clouds. The training laser (which is eye‑safe) fires at a much lower power and rate, with the result that the noted effects were not discovered until they were actually seen in combat–usually in the middle of a drop.[392]Bowing to the inevitable, General Shelton finally acknowledged the cumulative impact of these multiple untoward trends when he admitted to Congress at the beginning of May 1999 that there was “anecdotal and now measurable evidence… that our current readiness is fraying and that the long‑term health of the total force is in jeopardy.”[393]

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1054;