The Long and Short of Hit

The mysterious approaching monster from the section titled “Backbone” in Chapter 4 was mysterious because you mistakenly perceived a hit sound rapidly following the footstep; that is, you perceived the between‑the‑steps interval to be split into a short interval (from step to rapidly following hit) and a long interval (from that quick post‑step hit to the next footstep). The true gait of the approaching lilting lady had its between‑the‑steps interval broken, instead, into a long interval followed by a short interval. My attribution of mystery to the “short‑long” gait, not the “long‑short,” was not arbitrary. “Short‑long” is a strange human gait pattern, whereas “long‑short” is commonplace.

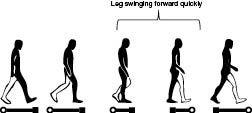

Your legs are a pair of 25‑pound pendulums that swing forward as you move, and are the principal sources of your between‑the‑steps hit sounds. A close look at how your legs move when walking (see Figure 41) will reveal why between‑the‑step hits are more likely to occur just before a footstep than just after. Get up and take a few steps. Now try it in slow motion. Let your leading foot hit the ground in front of you for its step. Stop there for a moment. This is the start of a step‑to‑step interval, the end of which will occur when your now‑trailing foot makes its step out in front of you. Before continuing your stride, ask yourself what your trailing foot is doing. It isn’t doing anything. It is on the ground. That is, at the start of a step‑to‑step interval, both your feet are planted on the ground. Very slowly continue your walk, and pay attention to your trailing foot. As you move forward, notice that your trailing foot stays planted on the ground for a while before it eventually lifts up. In fact, your trailing foot is still touching the ground for about the first 30 percent of a step‑to‑step interval. And when it finally does leave the ground, it initially has a very low speed, because it is only just beginning to accelerate. Therefore, for about the first third of a step, your trailing foot is either not moving or moving so slowly that any hit it does take part in will not be audible. Between‑the‑footsteps hit sounds are thus relatively rare immediately after a step. After this slow‑moving trailing‑foot period, your foot accelerates to more than twice your body speed (because it must catch up and pass your body). It is during this central portion of a step cycle that your swinging leg has the energy to really bang into something. In the final stage of the step cycle, your forward‑swinging leg is decelerating, but it still possesses considerable speed, and thus is capable of an audible hit.

Figure 41 . Human gait. Notice that once the black foot touches the ground (on the left in this figure), it is not until the next manikin that the trailing (white) foot lifts. And notice how even by the middle figure, the trailing foot has just begun to move. During the right half of the depicted time period, the white leg is moving quickly, ready for an energetic between‑the‑steps hit on something.

We see, then, that there is a fundamental temporal asymmetry to the human step cycle. Between‑the‑steps hits by our forward‑swinging leg are most probable at the middle of the step cycle, but there is a bias toward times nearer to the later stages of the cycle. In Figure 41, this asymmetry can be seen by observing how the distance between the feet changes from one little human figure to the next. From the first to the second figure there is no change in the distance between the feet. But for the final pair, the distance between the feet changes considerably. For human gait, then, we expect between‑the‑steps gangly hits as shown in Figure 42a: more common in mid‑step than the early or late stages, and more common in the late than the early stage.

Figure 42 . (a) Because of the nature of human gait, our forward‑swinging leg is most likely to create an audible between‑the‑steps bang near the middle of the gait cycle, but with a bias toward the late portions of the gait cycle, as illustrated qualitatively in the plot. (b) The relative commonness of between‑the‑beat notes occurring in the first half (“early”), middle, or second half (“late”) portions of a beat cycle. One can see the qualitative similarity between the two plots.

Does music show the same timing of when between‑the‑beat notes occur? In particular, are between‑the‑beat notes most likely to occur at about the temporal center of the interval, with notes occurring relatively rarely at the starts and ends of the beat cycle? And, additionally, do we find the asymmetry that off‑beat notes are more likely to occur late than early (i.e., are long‑shorts more common than short‑longs)? This is, indeed, a common tendency in music. One can see this in the classical themes as well, where I measured intervals from the first 550 themes in Barlow and Morgenstern’s dictionary, using only themes in 4/4 time. There were 1078 cases where the beat interval had a single note directly in the center, far more than the number of beat intervals where only the first or second half had a note in it. And the gaitlike asymmetry was also found: there were 33 cases of “short‑longs” (beat intervals having an off‑beat note in the first half of the interval but not the second half, such as a sixteenth note followed by a dotted eighth note), and 131 cases of “long‑shorts” (beat intervals having a note in the second half of the interval but not the first half, like a dotted eighth note followed by a sixteenth note). That is, beat intervals were four times more likely to be long‑short than short‑long, but both were rare compared to the cases where the beat interval was evenly divided. Figure 42b shows these data.

Long‑shorts are more common in music because they perceptually feel more natural for movement–because they are more natural for movement. And, more generally, the time between beats in music seems to get filled in a manner similar to the way ganglies fill the time between steps. In the Chapter 4 section titled “The Length of Your Gangly,” we saw that beat intervals are filled with a human‑gait‑like number of notes, and now we see that those between‑the‑beat notes are positioned inside the beat in a human‑gait‑like fashion.

Thus far in our discussion of rhythm and beat, we have concentrated on the temporal pattern of notes. But notes also vary in their emphasis. As we mentioned earlier, on‑beat notes typically have greater emphasis than between‑the‑beat notes, consistent with human movers typically having footsteps more energetic than their other gangly bangs. But even notes on the beat vary in their emphasis, and we take this up next.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 988;