Backbone

My family and I just moved into a new house. Knowing that my wife was unhappy with the carpet in the family room, and knowing how much she fancies tiled floor, I took the day off and prepared a surprise for her. I cut tile‑size squares from the carpet, so that what remained was a checkerboard pattern, with hardwood floors as the black squares and carpet as the white squares.

I couldn’t sleep very well that night on the couch, and so I headed into the kitchen for a bite. As I pondered how my plan had gone so horribly wrong, I began to notice the sounds of my gait. Walking on my newly checkered floor, my heels occasionally banged loudly on hard wood, and other times landed silently on soft carpet. Although some of my between‑step intervals were silent, between many of my steps was a strong bump or shuffle sound when my foot banged into the edge of the two‑inch‑raised carpet. The overall pattern of my sounds made it clear when my footsteps must be occurring, even when they weren’t audible.

Luckily for my wife–and even more so for me–I never actually checkered my living room carpet. But our world is itself checkered: it is filled with terrain of varying hardness, so that footstep loudness can vary considerably as a mover moves. In addition to soft terrain, another potential source of a silent step is the modulation of a mover’s step, perhaps purposely stepping lightly in order to not sprain an ankle on a crooked spot of ground, or perhaps adapting to the demands of a particular behavioral movement. Given the importance of human footstep sounds, we should expect that our auditory systems were selected to possess mechanisms capable of recognizing human gait sounds even when some footsteps are missing, and to “fill in” where the missing footsteps are, so that the footsteps are perceptually “felt” even if they are not heard.

If our auditory system can handle missed footsteps, then we should expect music–if it is “about” human movement–to tap into this ability with some frequency. Music should be able to “tell stories” of human movement in which some footsteps are inaudible, and be confident that the brain can handle it. Does music ever skip a beat? That is, does music ever not put a note on a beat?

Of course. The simplest cases occur when a sequence of notes on the beat suddenly fails to continue at the next beat. This happens, for example, in “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” when each “row” is on the beat, and then the beat just after “stream” does not get a note. But music is happy to skip beats in more complex ways. For example, in a rhythm like that shown in Figure 20, the first beat gets a note, but all the subsequent beats do not. In spite of the fact that only the first beat gets a note, you feel the beat occurring on all the subsequent skipped beats. Or the subsequent notes may be perceived to be off‑beat notes, not notes on the beat. Music skips beats and humans miss footsteps–and in each case our auditory system is able to perceptually insert the missing beat or footstep where it belongs. That’s what we expect from music if beats are footsteps.

Figure 20 . The first note is on the beat, but because it is an eighth note (lasting only half a beat), all the subsequent quarter notes (which are a beat in length) are struck on the off beat. You feel the beat occurring between each subsequent note, despite there being no note on the beat.

The beat is the solid backbone of music, so strong it makes itself felt even when not heard. And the beat is special in other ways. To illustrate this, let’s suppose you hear something strange approaching in the park. What you find unusual about the sound of the thing approaching is that each step is quickly followed by some other sound, with a long gap before the next step. Step‑bang . . . . . . Step‑bang . . . . . . “What on Earth is that?” you wonder. Maybe someone limping? Someone walking with a stick? Is it human at all?! The strange mover is about to emerge on the path from behind the bushes, and you look up to see. To your surprise, it is simply a lady out for a stroll. How could you not have recognized that?

You then notice that she has a lilting gait in which her forward‑swinging foot strikes the ground before rising briefly once again for its proper footstep landing. She makes a hit sound immediately before her footstep, not immediately after as you had incorrectly interpreted. Step . . . . . . bang‑Step . . . . . . bang‑Step . . . . . . Her gait does indeed, then, have a pair of hit sounds occurring close together in time, but your brain had mistakenly judged the first of the pair of sounds to be the footstep, when in reality the second in the pair was the footstep. The first was a mere shuffle‑like floor‑strike during a leg stride. Once your brain got its interpretation off‑kilter, the perceptual result was utterly different: lilting lady became mysterious monster.

The moral of this lilting‑lady story is that to make sense of the gait sounds from a human mover, it is not enough to know the temporal pattern of gait‑related hit sounds. The lilting lady and mysterious monster have the same temporal pattern, and yet they sound very different. What differs is which hits within the pattern are deemed to be the footstep sounds. Footsteps are the backbone of the gait pattern; they are the pillars holding up and giving structure to the other banging gangly sounds. If you keep the temporal pattern of body hits but shift the backbone, it means something very different about the mover’s gait (and possibly about the mover’s identity). And this meaning is reflected in our perception.

If musical rhythm is like gait, then the feel of a song’s rhythm should depend not merely on the temporal pattern of notes, but also on where the beat is within the pattern. This is, in fact, a well‑known feature of music. For example, consider the pattern of notes in Figure 21.

Figure 21 . An endlessly repeating rhythm of long, short, long, short, etc., but with neither “long” nor “short” indicated as being on the beat. One might have thought that such a pattern should have a unique perceptual feel. But as we will see in the following figure, the pattern’s feel depends on where the beat‑backbone is placed onto it. Human gait is also like this.

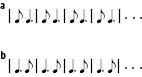

One might think that such a never‑ending sequence of long‑short note pairs should have a single perceptual feel to it. But that same pattern sounds very different in the two cases shown in Figure 22, which differ only in whether the short or the long note marks the beat. The first of these sounds jarring and inelegant compared to the second. The first of these is, in fact, like the mysterious monster we imagined approaching a moment ago, and the second is like the lilting lady the mover turned out to be.

Figure 22 . (a) A short‑long rhythm, which sounds very different from (and less natural than) the long‑short rhythm in (b) .

Music, like human gait‑related sounds, cannot have its beat shifted willy‑nilly. The identity of a gait depends on which hits are the footsteps, and, accordingly, the identity of a song depends on which notes are on the beat. And when a beat is not heard, the brain infers its presence, something the brain also does when a mover’s footstep is inaudible.

There are, then, a variety of suspicious similarities between human gait and the properties of musical rhythm. In the upcoming section, we begin to move beyond rhythm toward melody and pitch. We’ll get there by way of discussing how chords may fit within this movement framework, and how choreography depends on more than just the rhythm.

Although we’re moving on from rhythm now, there are further lines of evidence that I have included in the Encore, which I will only provide teasers for here:

Encore 1: “The Long and Short of Hit” Earlier in this section I mentioned that the short‑long rhythm of the mysterious monster sounds less natural than the long‑short rhythm of the lilting lady. In this part of the Encore, I will explain why this might be the case.

Encore 2: “Measure of What?” I will discuss why changing the measure, or time signature, in music modulates our perception of music.

Encore 3: “Fancy Footwork” When people change direction while on the move, their gait often can become more complex. I show that the same thing occurs in music: when pitch changes (indicative, as we will see, of a turning mover), rhythmic complexity rises.

Encore 4: “Distant Beat” The nearer movers are, the more of their gait sounds are audible. I will discuss how this is also found in music: louder portions of music tend to have more notes per beat.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1046;