The Length of Your Gangly

Every 17 years, cicadas emerge in droves out of the ground in Virginia, where I grew up. They climb the nearest tree, molt, and emerge looking a bit like a winged tank, big enough to fill your palm. Since they’re barely able to fly, we used to set them on our shoulders on the way to school, and they’d often not bother to fly away before we got there. And if they did fly, it wasn’t really flying at all. More of an extended hop, with an exoskeleton‑shaking, tumble‑prone landing. With only a few days to live, and with billions of others of their kind having emerged at the same time, all of them screeching mind‑numbingly away, they didn’t need to go far to find a mate, and graceful flight did not seem to be something the females rewarded.

Cicadas have, then, a distinctively cicada‑like sound when they move: a leap, a clunky clatter of wings, and a heavy landing (often with further hits and skids afterward). The closest thing to a footstep in this kind of movement is the landing thud, and thus the cicada manages to fit dozens of banging ganglies–its wings flapping–in between its landings. If cicadas were someday to develop culture and invent music that tapped into their auditory movement‑recognition mechanisms, then their music might have dozens of notes between each beat. With Boooom as their beat and da as their wing‑flap inter‑beat note, their music might be something like “Boooom‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑Boooom‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da‑da,” and so on. Perhaps their ear‑shattering, incessant mating call is this sound!

Whereas cicadas liberally dole out notes in between the beats, Frankenstein’s monster in the movies is a miser with his banging ganglies, walking so stiffly that his only gait sounds are his footsteps. Zombies, too, tend to be low on the scale of banging‑gangly complexity (although high on their intake of basal ganglia).

When we walk, our ganglies are more complex than those of Frankenstein and his zombie dance buddies, but ours are doled out much more sparingly than the cicadas’. During a step, your leg swings forward just once, and so it can typically only get one really good bang on something. More complex behaviors can lead to more bangs per step, but most commonly, our movements have just one between‑the‑footsteps bang–or none. Our movements tend to sound more like the following, where “Boooom ” is the regularly repeating footstep sound and “da” is the between‑the‑steps sound: “Boooom‑Boooom‑Boooom‑da‑Boooom‑Boooom‑da‑Boooom‑da‑Boooom‑da‑da‑Boooom‑da‑Boooom‑da‑Boooom .” (Remember to do the “Boooom ” on the beat, and cram the “da ”s in between the beats.)

Given our human tendency to make roughly zero to one gangly bang between our steps, our human music should tend to pack notes similarly lightly between the beats. Music is thus predicted to tend to have around zero to one between‑the‑beats note. To test for this, we can look at the distribution of time gaps between musical notes. If music most commonly has about zero to one note between the beats–along with notes usually on the beat–then the most common note‑to‑note time gap should be in the range of a half beat to a beat.

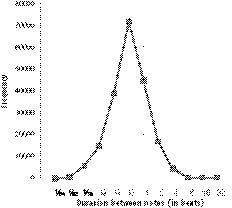

To test this, as an RPI graduate student, Sean Barnett analyzed an electronic database of Barlow and Morgenstern’s 10,000 classical themes, the ones we mentioned at the start of this chapter. For every adjacent pair of notes in the database, Sean recorded the duration between their onsets (i.e., the time from the start of the first note to the start of the second note). Figure 19 shows the distribution of note‑to‑note time gaps in this database–which time intervals occur most commonly, and which are more rare. The peak occurs at ½ on the x ‑axis, meaning that the most common time gap is a half beat in length (an eighth note). In other words, there is one note between the beats on average, which is broadly consistent with expectation.

Figure 19 . The distribution of durations between notes (measured in beats), for the roughly 10,000 classical themes. One can see that the most common time gap between notes is a half beat long, meaning on average about one between‑the‑beat note. This is similar to human gait, typically having around zero to one between‑the‑step “gangly” body hit.

We see, then, that music tends to have the number of notes per beat one would expect if notes are the sounds of the ganglies of a human–not a cicada, not a Frankenzombie–mover. Musical notes are gangly hits. And the beat is that special gangly hit called the footstep. In the next section we will discuss some of what makes the beat special, and see if footsteps are similarly special (relative to other kinds of gangly hits).

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1185;