Nature’s Other Phoneme

I have been treating hits and slides as two different kinds of physical interaction. But slides are more complex than hits. This is because slides consist of very large numbers of very low‑energy hits. For example, if you rub your fingernail on this piece of paper, it will be making countless tiny collisions at the microscopic level. Or, if you close this book and run your fingernail over the edges of the pages of the book, the result will be a slide with one little hit for each page of the book. But it would not be sensible to conclude, on this basis, that there are just two fundamental natural building blocks for events–hits and rings–because describing a slide in terms of hits could require a million hits! We still want to recognize slides as one of nature’s phonemes, because slides are a kind of supersequence of little hits that is qualitatively unlike the hits produced when objects simply collide.

But there are implications to the fact that slides are built from very many hits, but not vice versa: that fact opens up the possibility of a fundamental event type that is not quite a hit, and not quite a slide. To understand this new event type, let’s look at a slide at the level of its million underlying hits. Imagine that the first of these million hits is appreciably more energetic than the others. If this were the case, then the start of the slide would acquire a crispness normally found in hits. But this hit would be just the first of a long sequence of hits, and would thus be part of the slide itself. Such a hit‑slide would, if it existed, be neither a hit nor a slide.

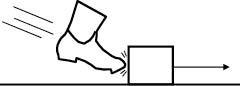

And they do exist, for several converging reasons. First, slides have a tendency to be initiated by hits. Try sliding this book on a desk. The first time you tried, you may have bumped your hand into the book in the process of attempting to make it slide. That is, you may have hit the book prior to the slide (see Figure 5). It requires careful attention to gently touch the book without hitting it first. Now grab hold of the book and try to slide it without an initial hit. Even in this case there can often be an initial hitlike event. This is because in order to slide an object, you must overcome static friction, the “sticky” friction preventing the initiation of a slide. This initial push is hitlike because the sudden overcoming of static friction creates a sudden burst of many frequencies, as in Figure 4a. Slides, then, often begin with a hit. Second, hits often have slides following them. If you hit a wall with a straight jab, you will get a lone hit, with no follow‑up slide. But if you move your arm horizontally next to the wall as you are hitting it–in order to give it a more glancing blow–there will sometimes be a small skid, or slide, after the initial hit.

Figure 5 . A hit‑slide is a fourth fundamental constituent of physical events. It sounds like a kind of phoneme in language called the affricate, which is like a plosive followed by a fricative.

Although a hit followed by a slide is a natural regularity in the world, a slide followed by a hit is not a natural physical regularity. First, it is common to have a hit not preceded by a slide. To see this, just hit something. Odds are you managed to make a hit without a slide first. Second, when there is a slide, there is no physical regularity tending to lead to a hit. Slides followed by hits are possible, of course–in shuffleboard, for example (and note the fricatives in “shuffle”)–but they really are two separate events in succession. A hit‑slide, on the other hand, can effectively be a single event, as we discussed a moment ago.

If language sounds like nature, then we should expect linguistic hit‑slide sounds to be more common than slide‑hit sounds. Later in this chapter–in the section titled “Nature’s Words”–I will provide evidence that this is true of the way phonemes combine into words across human languages. But in this section I want to focus on the single‑phoneme level. The question is, since hit‑slides are a special kind of fundamental event atom, but slide‑hits are not, do we find that languages have phonemes that sound like hit‑slides, but not phonemes that sound like slide‑hits?

Languages, like nature, are asymmetrical in this way. There is a kind of phoneme found in many languages called an affricate , which is a fricative that begins as a plosive. One example in English is “ch,” which is a single phoneme that possesses a “t” sound followed by a “sh” sound. In addition to words like “chair,” it also occurs in words like “congratulate” (spoken like “congratchulate”), and often in words like “trash” (spoken like “chrash”). Another example is “j,” which begins with “d” sound followed by a voiced version of the “sh” phoneme. Although we can describe “ch” as a “sh” initiated by a “t,” it is not the same sound that occurs when we say “t” and quickly follow it up with “sh.” The “ch” phoneme has the “t” and “sh” sounds bound up so closely to one another that they sound like a single atomic event. The “tsh” sound in “hotshot,” on the other hand, will typically sound different from “ch”; that is, we do not pronounce the word “ha‑chot.”

Whereas language has incorporated nature’s hit‑slide phoneme as one of its phoneme types, slide‑hits, on the other hand, are not one of nature’s phonemes, and a harnessing language is not expected to have phonemes that sound like slide‑hits. Indeed, that is the case. Languages do not have the symmetric counterpart to affricates–phonemes that sound like a plosive initiated by a fricative. It is not that we can’t make such sounds–“st” is a standard sound combination in English of this slide‑hit form, but it is not a single phoneme. Other cases would be the sounds “fk” and “shp,” which occur as pairs of phonemes in words in some languages, but not as phonemes themselves.

By examining physics in greater detail, in this section we have realized that there is a fourth fundamental building block of events: hit‑slides. And just as languages have honored the other three fundamental event atoms as their principal phoneme types, this fourth natural event atom is also so honored. Furthermore, the symmetrical fifth case, slide‑hits, is not a fundamental event type in nature, and we thus expect–if harnessing has occurred–not to find fricative‑plosives as language phonemes. And indeed, we don’t find them.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1218;