SCHUTZHUND

THEORY AND TRAINING METHODS

What Is Schutzhund?

“Joy in work, devotion to duty and to master… docility and obedience, teachableness and quickness to understand.”–Max von Stephanitz

The ideal dog possesses certain inherent qualities of character. It is a friendly, good‑natured family member; an alert, courageous protector and an obedient, reliable companion. These qualities are not only the products of its upbringing and how it was taught to behave. They are also the result of its genetic endowment–the quality of its parents, its grandparents and their parents, too.

Schutzhund is a sport whose purpose is to evaluate a dog’s character by giving it work to do, and then comparing its performance with that of other working dogs. In German, the word Schutzhund means literally protection dog , for that is what a Schutzhund is meant to be. The sport evolved in Germany around the turn of the twentieth century as a means of testing and preserving the character and the utility of working dogs.

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Western Europe was well populated with many types of rural shepherd dogs. These animals herded sheep, cattle and other livestock for their masters. They also guarded livestock at night and gave warning of the approach of strangers to innumerable small farms and hamlets. Shepherd dogs were an indispensable part of the farm economy.

These dogs did not belong to breeds per se. Rather, their size, build, coat and color conformed to types that were traditional in various regions, and blended smoothly from one region to the next. At this time, ownership of actual breeds of pedigreed dogs was primarily a privilege of the noble and the wealthy, who devoted themselves mainly to sight hounds, trail hounds and other dogs of the chase. In contrast, rural shepherd dogs were kept and bred by generation after generation of peasants and farmers. People of means and wealth had as little regard for peasant dogs as they did for peasants, and in comparison to a noble hound of St. Hubert, a shepherd dog was little more than a cur.

It was not until some time later, near the end of the nineteenth century, that some members of the leisure class who had both the time and money to keep and breed dogs simply for pleasure took an interest in the common farm dogs of the countryside. For perhaps the first time these animals were viewed as altogether more valuable than the livestock they guarded, and in various areas of Europe certain unusual men began to take steps to preserve and develop them.

One of these was an aristocratic young German cavalry officer named Max von Stephanitz who in 1899 founded the German Shepherd Dog Club of Germany (called the SV). The importance of von Stephanitz in the establishment and development of the German Shepherd cannot be overestimated. Almost single‑handedly he built the breed. He presided over the club, began the stud book, wrote the standard of the breed and appointed the judges who would select the most worthy specimens. He also organized training contests for the SV. Well before von Stephanitz’s time, numerous informal contests were conducted in small villages all over Europe, but it was he who formalized these competitions under the auspices of the SV and structured them to include tests of performance in tracking, obedience and protection. These training contests became the sport we know today as Schutzhund.

Von Stephanitz was totally committed to the idea that the German Shepherd is, and must stay, a working animal whose worth is derived from its utility. He strongly encouraged the use of dogs by the German police and military. There was a great need, he felt, for an animal that possessed a “highly developed sense of smell, enormous courage, intrepidness, agility and, despite its aggressiveness, great obedience.” Von Stephanitz was a man of vision. From its founding in 1899, the SV prospered for thirty‑six years under his absolute control. In addition to building a prosperous and effective organization, he also put in place a system of strict controls that guided the breeding of the German Shepherd in Germany during the first half of the twentieth century.

Today the SV is the largest and most influential breed organization in the world, and it continues much in the tradition of von Stephanitz. The system he put into effect decades ago still serves to preserve and develop the best physical and temperamental attributes of the breed, and Schutzhund is an integral part of this system. Among the SV’s regulations for controlled breeding, the most basic requirement for breed worthiness is the Schutzhund examination.

A German Shepherd Dog in Germany cannot receive official registration papers unless both of its parents have passed a Schutzhund trial. Furthermore, unless the dog itself also passes a Schutzhund examination, it cannot be exhibited in conformation shows; it is not eligible for the coveted V rating (for Vorzüglich , excellent) in beauty and structure; it may not compete for the title of Sieger (Champion) of Germany; it will not be recommended for breeding by a Körmeister (breed master).

By ensuring that a dog will only be used for breeding if it has the necessary character and working attributes to pass a performance test, the Germans have guaranteed a long legacy for the German Shepherd as a working animal.

Nineteenth‑century German farm and herding dogs. Top, two smooth‑coated shepherds photographed circa 1880. Right, a rough‑coated shepherd from Württemberg.(Fromvon Stephanitz, The German Shepherd Dog, 1923.)

An early SV‑registered German Shepherd: Hussan v. Mecklenburg, a son of the 1906‑1907 German Sieger Roland v. Starkenburg. (From von Stephanitz, The German Shepherd Dog, 1923.)

The Schutzhund trial is a day‑long test of character and trainability; it is an evaluation of the dog’s stability, drive and willingness. The animal must be a multitalented generalist that can, in the space of one day, compete successfully in three entirely different phases of performance: tracking, obedience and protection. Schutzhund I is the most elementary title awarded, while Schutzhund III demands the most challenging level of ability.

The tracking test assesses the dog’s perseverance and concentration, its scenting ability and its willingness to work for its handler. The animal must follow the footsteps of a tracklayer, finding and indicating to its handler objects, called articles , that the tracklayer has left on the track. With each category (Schutzhund I, II or III), the length and age of the track are increased.

Obedience evaluates the dog’s responsiveness to its handler. The obedience test involves a number of different situations in which the dog must eagerly and precisely carry out its handler’s orders. It must be proficient at heeling at its handler’s side, retrieving, jumping and performing a variety of skills.

The protection phase gauges the dog’s courage, desire for combat, self‑reliance and obedience to its handler under very exciting and difficult circumstances. This phase involves searching for and warning its handler of a hidden “villain,” aggressively stopping an assault on its handler and preventing the escape of the villain, among other skills.

The trial is presided over by a recognized judge. It is understood that the judge will be a fellow trainer, a person who has years of experience with working dogs. He must have “feeling” for the animals and be able to look at the whole picture of what a working dog represents. The judge is expected to have the ability to watch a dog work for a little while and then know what is in its heart–what it has inside.

The judge’s job is ostensibly to determine a winner. But possibly more important, his job is to promote those animals that display outstanding quality of character so that they will be used for breeding (providing they also meet a number of other requirements for beauty and physical soundness), and to weed out those animals that are deficient or unsound in character. Accordingly he can, and will, disqualify a dog at any point during a trial if the animal shows a severe temperamental flaw.

The Schutzhund trial is sanctioned and organized by a local Schutzhund club, which is part of a large Schutzhund organization. Although there are some professionals who make their living through the sport, Schutzhund breeding and training are meant to be amateur pursuits, and a reputable club is strictly a nonprofit group.

In Germany, the two largest Schutzhund organizations are the SV (the German Shepherd Dog Club) and the DVG (the German Alliance for Utility Dog Sports). The trial rules and regulations of both organizations are essentially identical. However, the emphasis is slightly different in each. While the SV is a breed club dedicated to the promotion of the German Shepherd Dog, the DVG is a training club that accepts a number of other breeds besides the German Shepherd in competition. The SV emphasizes the character test and breed worthiness aspects of Schutzhund, and the SV judge looks not only at the training of a dog in trial but also at its quality, asking himself if that dog should be used to produce other German Shepherd Dogs. The DVG emphasizes the sport and competition aspects of Schutzhund, and the DVG judge looks primarily at the dog’s training and how well its handler presents the animal in trial.

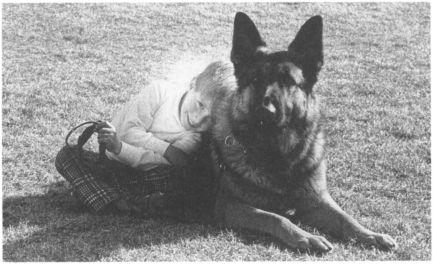

The ideal dog is a friendly, good‑natured family member, an alert, courageous protector and an obedient, reliable companion. (Andy Barwig and Susan Barwig’s “Uri” Schutzhund III, UDT.)

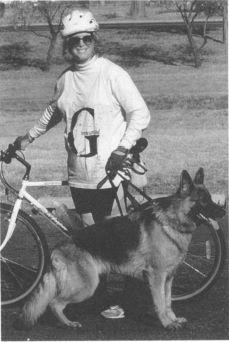

The German Shepherd Dog Club of Germany’s system of regulating breeding. In addition to fulfilling a hip X‑ray requirement and passing a Schutzhund trial and a breed survey examination, the dog must also complete without difficulty a twelve‑mile endurance test before being eligible for breeding. (V Jasmine v. Forellenbach, Schutzhund II, with Dr. Nancy Cole.)

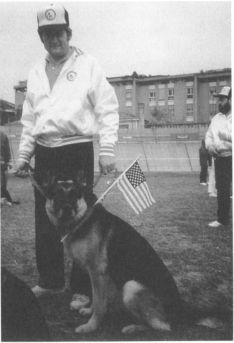

America in international Schutzhund competition–Leo Muller and “Argo” representing the United States at the World Championships in Italy.

Normally small and friendly, each local club is part of the larger Schutzhund community. A Schutzhund enthusiast from just about anywhere can expect a nice reception at a club in another province, or even in another country.

The club serves a social function as well, especially in Europe. Families and friends get together on training days to eat, drink, laugh and tell tales in the clubhouse and around the field as the dogs run through their routines. The closeness and team spirit of a good club are in evidence. Because everyone is nervous, all the competitors and club members support and encourage one another.

Through its commitment to Schutzhund and its uncompromising insistence on strictly controlled breeding practices, the SV has succeeded in producing the best German Shepherd Dogs in the world. As a result, German‑bred German Shepherds are exported by the thousands to places as far away as Japan and Hong Kong. Along with their dogs, Germans have also exported their dog sport. Schutzhund trials have spread to countries throughout the world, including Africa, Australia, South America, North America and even Soviet bloc countries. In many countries stadiums fill with people and brim with excited anticipation when Schutzhund contests take place. In Europe, for example, approximately 40,000 German Shepherds participate in 10,000 trials each year. Besides German Shepherds, many other breeds of dog now compete, including Boxers, Doberman Pinschers, Giant Schnauzers, Bouviers des Flandres, Rottweilers and Belgian shepherds (Groenandael, Malinois and Tervuren).

Despite its longtime popularity in Europe, Schutzhund has only recently come to the United States. The first Schutzhund‑type trial on American soil was organized in June 1963 by the Peninsula Canine Corps of Santa Clara, California. The Peninsula Canine Corps was formed in 1957, and boasted as its prime mover Gernot Riedel, a German emigrant who has been an important figure in the American dog sport ever since. The trial was not officially sanctioned, and did not even include tracking, but it was a beginning.

As we seem to do with many newly introduced competitive sports, Americans grew to prominence in Schutzhund with a speed that astounded the skeptics. In 1969, six years after the initial competition in California, the first SV‑sanctioned trial on American soil took place in Los Angeles under the leadership of Henry Friehs, another German emigrant. In the same year Alfons Erfelt (of American Temperament Test Society fame) and Drs. Preiser and Lindsey formed the North American Schutzhund Association (NASA).

In 1975, a large group of American Schutzhund pioneers, including Phil Hoelcher, Gernot Riedel, Bud Robinson and Mike McKown, convened in Dallas to try to reconcile the ambitions of the dozen or more local Schutzhund clubs that existed at the time. The result was the founding of the United Schutzhund Clubs of America (USA) under the chairmanship of Luke MacFarland. Scarcely two years later the USA fielded its first team at the World Union of German Shepherd Clubs’ European Schutzhund III Championship (consisting of Phil Hoelcher with Cliff vom Endbacher Forst, Wayne Hammer with Nikko von der Ruine Engelhaus and Gernot Riedel as team captain).

Around 1978, an early American branch of the DVG called Working Dogs of America (WDA) dissolved in some dispute. DVG America was obliged to limp along only until the next year, when a sharp and acrimonious conflict of policies and personalities resulted in the expulsion from the USA of seven influential trainers, including Phil Hoelcher, Tom Rose, Laddy Nethercutt, Pat Patterson and Mary Coppage. They immediately went over to the DVG, and with their help DVG America quickly burgeoned, becoming especially important in Florida, one of the hot spots for the dog sport in the United States.

In 1983, the German Shepherd Dog Club of America (GSDCA) allowed some of its members to form an adjunct to the club, which they called the German Shepherd Dog Club of America Working Dog Association (GSDCA/ WDA) and which was somewhat nebulously associated with its parent organization. It had to be done this way because of the GSDCA’s fear of displeasing the American Kennel Club, which has frowned upon Schutzhund since the beginning. (Earlier, in 1973 and 1974, the GSDCA had conducted a brief flirtation with Schutzhund, sponsoring trials and scheduling judges provided by the SV, but the GSDCA disavowed the sport in 1975 primarily because of AKC objections.)

Today, Schutzhund is firmly established on American shores. Although DVG America is thriving, and the GSDCA/WDA is still on the scene, the USA is the largest and most important organization in the States, boasting approximately two hundred clubs. Recently, the USA has even taken steps to adopt a regulated breeding system for German Shepherd Dogs much like the SV’s, issuing its own pedigrees and so forth. However, while the USA’s primary emphasis is upon promoting the German Shepherd, the organization welcomes all breeds in its competitions.

American Schutzhund enthusiasts have traveled a rocky road. Organizations and personalities have come and gone, and there have been a lot of fireworks on the way, but today American teams have become a powerful force in the international Schutzhund community. For the last several years teams fielded by the GSDCA/WDA and the USA have consistently placed high in the World Schutzhund III Championships, and in both 1988 and 1989 Jackie Reinhart of Florida won the German DVG Schutzhund III Championships outright.

There are a variety of reasons that account for the rapid growth of Schutzhund in this country. Many dogs trained in Schutzhund are now used by police forces and the military, as search and rescue dogs, as personal protection dogs and as companions in private homes. Growing fear of personal assault and the need to protect property, as well as the desire for a trustworthy, outgoing family pet, have all contributed to the popularity of the Schutzhund concept.

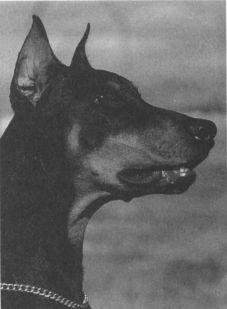

Doberman Pinscher. (Linda Tobiasz’s “Kristoff,” Giant Schnauzer. Schutzhund I.)

Giant Schnauzer.

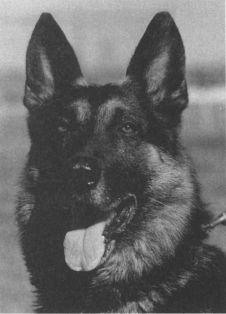

German Shepherd. (Susan Barwig’s V “Ajax,” Schutzhund III, FH.)

Belgian Malinois. (Charley Bartholomew’s “Utha.”)

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1955;