The dog is not frightened.

2. It is very sensitive and reacts aggressively.

3. It is timid and backs away.

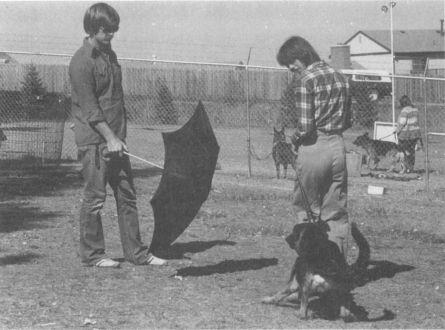

The dog’s reaction to visual stimuli can be noted as well. An umbrella is opened abruptly at a distance of approximately five feet from the dog. Possible reactions are the same as those for noise, above.

In all the auditory and visual tests, it is extremely important to evaluate how the dog recovers from stress. If it reacts strongly and adversely to a stimulus but then adjusts quickly to the situation, this is a very positive indication. It is unrealistic to expect either a puppy or an adult to be completely brave. At one point or another in their lives, all dogs will experience fear. Our main concern is how they deal with it.

The final test of confidence involves the approach of two strangers. The first is friendly to the handler and the dog. From this encounter we can draw certain conclusions. If the dog is friendly to the stranger, it indicates self‑confidence. On the other hand, if it retreats from a harmless stranger, we can conclude that it lacks boldness. Next, the second stranger approaches the dog in a threatening manner, appearing as suspicious and ominous as possible. If the dog becomes alert and threatens the stranger, the stranger retreats. This test is only performed on older puppies of at least twelve months. It is important to note that a hysterically aggressive reaction is as undesirable as dullness or outright fear. We prefer the dog that surges forward into the leash, possibly barking, and shows a strong desire to make physical contact with the hostile stranger.

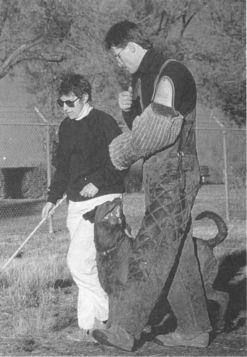

One of the most commonly used tests of a dog’s fighting spirit is the Henze courage test, modified by the Menzels, which proceeds as follows: “The agitator runs away quickly. As soon as he has run some fifty paces the dog is set loose and encouraged to ‘get’ the fleeing man. Right before the dog reaches him, the agitator turns and threatens the dog with a stick and by yelling at it.” Fighting spirit is seen in the dog that flies into the agitator without slowing down and bites as hard and as full as it can (the agitator wears a sleeve).

This test is one of the integral parts of the Schutzhund examination. Although very revealing in many cases, the Henze courage test must be interpreted in light of the dog’s past experience. A dog that performs a creditable courage test without any previous experience in bite‑work training would rate as extraordinarily powerful in nearly anyone’s book, an example of an exceptionally good genetic endowment. However, we must look differently at another dog that has its Schutzhund III and that has already received a great deal of training in bite work. When this animal bites well during the courage test, its performance is not so much a demonstration of good character as of good training. To put it another way, its character is masked by its training and will only be more fully revealed in a situation that is more unusual for it.

The umbrella test. The tester opens an umbrella suddenly at an approaching dog. This animal is frightened and recoils violently.

The umbrella test. This puppy exhibits a touch of apprehensiveness in response to the pop of the umbrella, but does not recoil and shows willingness to approach it.

The final part of the courage test, which is called the “double stimulus” test, serves to unmask those dogs that bite because they have been trained to bite the sleeve rather than because they desire to protect their handler. After the dog is engaged in a fight with an agitator wearing a sleeve, the agitator then stands motionless. An unprotected assailant (no sleeve and no protective clothing to “key” the dog) then attacks the dog’s handler. It is fascinating to observe whether the dog will continue to guard the agitator with the sleeve, or if it will defend its handler from attack. (The dog is on leash and wears a leather muzzle during this test.) Interestingly enough, normally the more formal bite‑work training the animal has undergone, the more preoccupied it will be with the sleeve and thus the less likely it will be to defend its handler. On the other hand, few untrained dogs will have the nerve to try to bite either person when muzzled like this.

Many of these evaluative tools have now become part of police dog tests in Germany and elsewhere.

To summarize, the very promising Schutzhund dog will:

1. show both interest in searching for its handler and also a tendency to immediately use its nose in order to do so

2. be very interested in playing with and retrieving objects thrown for it

3. be either undisturbed by the approach of a friendly stranger or overtly friendly toward him

4. show both an eagerness to follow its handler and stay near him as well as a tendency to go off exploring on its own

5. be frightened by very little, and when it is frightened by something it will soon lose its fear and forget the incident

6. immediately and vigorously bite any object like a burlap sack that is moved rapidly past it and be oblivious of any attempt to frighten it

7. move very strongly toward a menacing stranger (when the dog is at least one year old), trying to make physical contact with him, but not exhibiting any signs of hysterical or fear‑motivated aggressiveness.

In protection, it is not only the handler who trains the dog–the decoy plays a vital role. While it is often possible to successfully train a dog using a good decoy and a bad handler, it is usually impossible to train a dog using a good handler and a bad decoy. Accordingly, in addition to all of the special skills and abilities peculiar to a skilled decoy, the person who agitates the dog must have integrity, intelligence and self‑discipline. (Janet Birk and Chesapeake Bay Retriever “Jason,” Schutzhund III, working on Stewart Hilliard.)

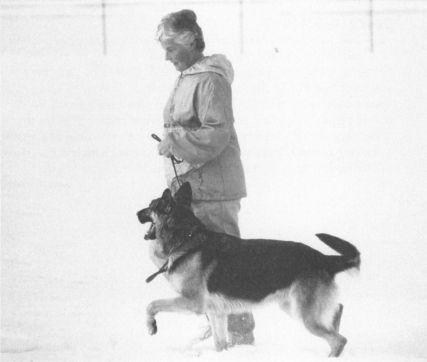

“Mucke” works happily for handler Barbara Valente because Barbara has taught the dog a perfect understanding of all skills and a lively pleasure in accomplishing them.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1129;