Unification of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms waged a constant struggle against one another for predominance over the country. From time to time some stronger state seized the land of the neighbouring kingdoms and made them pay tribute, or even ruled them directly. The number of kingdoms was always changing; so were their boundaries.

The greatest and most important kingdoms were Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex. For a time Northumbria gained supremacy. Mercia was the next kingdom to take the lead. The struggle for predominance continued and at last at the beginning of the 9th century Wessex became the strongest state. In 829 Egbert[5], King of Wessex, was acknowledged by Kent, Mercia and Northumbria. This was really the beginning of the united kingdom of England, for Wessex never again lost its supremacy and King Egbert became the first king of England. Under his rule all the small Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were united to form one kingdom which was called England from that time on[6].

The clergy, royal warriors and officials supported the king's power. It was the king who granted them land and the right to collect dues from the peasants and to hold judgement over them. In this way the royal power helped them to deprive the peasants of their land and to turn them into serfs.

The political unification of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms was sped up by the urgent task of defending the country against the dangerous raids of the new enemies. From the end of the 8th century and during the 9th and the 10th centuries Western Europe was troubled by a new wave of barbarian attacks. These barbarians came from the North – from Norway, Sweden and Denmark, and were called Northmen. In different countries the Northmen were known by many other names, as the Vikings, the Normans, the Danes. They came to Britain from Norway and Denmark.

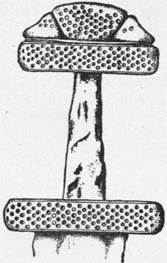

A viking sword handle of the 9th century

But more often the British Isles were raided from Denmark, and the invaders came to be known in English history as the Danes.

TERROR OF THE NORSEMEN

The first Viking raids, from around 790, were no more than that, hit-and-run attacks by seaborne pirates finding rich and undefended targets close to shore, such as the monastery of Lindisfarne. Their paganism added a sinister aspect to what even by the standards of the time was appalling brutality. With little space in their ships to take slaves, they killed males indiscriminately but carried off girls and women. Within a very few years it was obvious that a profoundly unsettling new element had entered into the world of Anglo-Saxons, Britons, Picts and Scots. Perceived at first as nothing more than a harassment, the Norsemen became a very serious threat to all the established kingdoms of the British Isles. Early in the ninth century they were ceasing to be sporadic external raiders, and forming a new, strong and enduring element in the regional power-structure. There is a hard historical irony in their resemblance to the Angles and Saxons themselves of a few generations back. Like these, the Vikings were pagan. They came from the same part of northern Europe. Their language and their customs were in many ways similar to those of the Anglo-Saxons. But the Vikings were harsher, more extreme in their idolisa-tion of violence and their warrior cult. There is ample evidence that they were found to be utterly terrifying.

The Danish raids were successful because the kingdom of England had neither a regular army nor a fleet in the North Sea to meet them. There were no coastguards to watch the coast of the island and this made it possible for the raiders to appear quite unexpectedly. Besides, there were

very few roads, and large parts of the country were covered with pathless forests or swamps. It took several weeks sometimes before anyone could reach a settlement from where a messenger could be sent to the king, or to the nearest great and powerful noble, to ask for help. Help was a long time in coming. It would take the king or the noble another few weeks to get his fighting men together and go and fight against the enemy.

Northumbria and East Anglia suffered most from the Danish raids. The Danes seized the ancient city of York and then all of Yorkshire. Here is what a chronicler wrote about the conquest of Northumbria: "The army raided here and there and filled every place with bloodshed and sorrow. Far and wide it destroyed the churches and monasteries with the fire and sword. When it departed from a place, it left nothing standing but roofless walls. So great was the destruction that at the present day one can hardly see anything left of those places, nor any sign of their former greatness." Soon after, the Danes conquered East Anglia and slew King Edmund. (The Christians considered him a martyr, and a monastery was built where he was buried and the town still bears his name – Bury St. Edmunds.) Then large organized bands of Danes swept right over to the midlands. At last all England north of the Thames, that is, Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia, was in their hands.

Only Wessex was left to face the enemy. Before the Danes conquered the North, they had made an attack on Wessex, but in 835 King Egbert defeated them. In the reign of Egbert's son the Danes sailed up the Thames and captured London. Thus the Danes came into conflict with the strongest of all the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Wessex.

The West Saxons found the lately conquered Cornish allying with Norsemen to reclaim their territory, and Egbert defeated them at Hingston Down, near Plymouth, in 838. Other Norse groups raided into Mercia and Northumbria. Nowhere in England was very far from the sea, or from a navigable river, and nowhere could feel safe from a sudden devastating raid. Local resistance was often strong, including a naval battle, the first to be recorded in English history, off Sandwich in Kent, when a fleet of raiders was beaten back in 851. Larger-scale resistance was rare or non-existent, and the overlordship of the Wessex kings was a meaningless dignity when Wessex could not even defend itself against the marauders. In 864 they stormed and burned down its capital, Winchester. So far, the Viking raids had been opportunistic, led by many war-chiefs who owed allegiance to no one. Around 865, their campaigning took a different turn, and it became clear that they were fighting to gain and hold the land. Under two leaders of high rank, Ivar 'the Boneless' and his brother, Halfdan, an army landed in East Anglia. Over the next ten years, a vast extent of eastern England was brought under Norse rule. Northumbria was first to be subjugated, and its old Roman-British-Saxon capital became the Viking town of Jorvik. Eastern Mercia was overrun, and in 869 East Anglia and Essex were added. The pious Anglian king, Edmund, killed by the victors, was buried by his people where Bury St Edmunds now stands. The Norsemen now turned inland and forced their way up the line of the Thames and along the Downs. The conquest of Mercia was completed.

ALFRED THE GREAT

In 871, the fourth and youngest son of Aethelwulf, Alfred, had become King of Wessex, a much-assailed and reduced kingdom. He bribed the Norsemen to stop their further advance westward; instead they swept north. By 876, they returned. Under Alfred, the West Saxons put up a fierce resistance but they were gradually driven back until, at the lowest point of his fortunes, Alfred took refuge at Athelney in the Somerset marshes in the spring of 878. From here he rallied his forces to defeat the Danish leader, Guthrum, at the battle of Edington in May of that year. This was followed up by Guthrum's surrender and promise to adopt Christianity, set out in the Treaty of Wedmore.

Only one English king has ever been dubbed 'the Great'. Though he never ruled more than Wessex, Kent and part of Mercia, Alfred earned this description not only through his prowess and steadfastness as a military leader but also by his statesmanship, scholarship and care for his nation. Unlike previous kings such as Offa, he was a man of culture who thought deeply about moral issues. The national tradition of England stems from his success, for otherwise, whatever country ultimately emerged from Viking conquest, it would have had another name and perhaps its destiny set on other paths. His arrest of the Norsemen's progress made it possible for his successors to regain for the Anglo-Saxons what had been lost to the invaders. Although it is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the history of national events founded by Alfred himself, that says so, there is no reason to doubt its comment that: 'all the English people submitted to Alfred except those who were under the power of the Danes.' To those who feared conquest, and to those already conquered, the King of Wessex offered the only real hope.

While he had peace, Alfred prepared for war, renewing his army and creating a fleet to guard the coasts, and building fortifications round his main towns. War duly recurred in 886 and 892, with new Danish invasions, and the Danish kingdoms of eastern England coming to their support. Between 892 and 896, there was again open warfare as a further effort was made to make England a wholly Viking country; it was a bitter campaign and in the end the raiders turned away to find easier pickings in northern Europe. England was left a divided country. North of a line from London to Chester were kingdoms of the Norsemen, East Anglia, the land of the 'Five Boroughs' of Lincoln, Nottingham, Derby, Leicester and Stamford, ruled by independent earls, and the kingdom of Jorvik – more than half of the country in overall extent. This was the Danelaw, a great swathe of the country where the Norse imprint would remain for centuries to come, long after the establishment of a unified state. Place names, local dialect words, even regional accents, reveal the long period of occupation and colonization and the slow commingling of the Norse and Anglo-Saxon populations.

ALFRED'S SUCCESSORS

The frontier was not a natural one and was inevitably transgressed. The Anglo-Saxons did not remain united. When Alfred's son, Edward, succeeded him in 899, a disaffected cousin joined the Danes and invaded Wessex, causing three years of warfare. Inheritance was always likely to cause trouble in cases like this, where the grown sons of Alfred's elder brother had at least as much claim to the kingship as the son of Alfred. The right of a king's eldest son to inherit was still far from being accepted practice. Western Mercia had been under a sub-king, whose widow was Edward's sister, Aethelflaed, ‘Lady of Mercia’; and brother and sister operated a co-ordinated policy, responding to incursions from the Danelaw by attacking and annexing territory. The last Danish King of East Anglia was killed in battle in 921. By Edward's death in 924, the realm he had inherited had been greatly enlarged to encompass all thе country south of the Humber. His son, Athelstan, first secured York as a sub-kingdom and then took it over. This was empire-building on a scale not seen before. The princes and chiefs of Wales also acknowledged his power by the payment of a large annual tribute. Cornwall, whose British population was again restive under English rule, was invaded and forcibly pacified. For the first time since Britannia was a single Roman province, one man could claim to be master of all England, and Athelstan s prestige was such that his numerous sisters were sought as brides by great European potentates, even Emperor Otto I. It was in support of one of his European alliances that Athelstan sent the first English force to intervene in continental power politics, in 939. Within Great Britain, Athelstan had made the Kings of Strathclyde and of the Scots acknowledge his supremacy in 927. Ten years later, they combined with Irish Vikings to attack him. But at the unidentified site of Brunanburh, Athelstan soundly defeated them. His assemblage of kingdoms and statelets barely lasted for his lifetime, however. By 939 the Vikings under Olaf Guthfrithson had retaken York and in the following year re-established a Viking kingdom around it. Though Athelstan's successors, Edmund and Eadred, fought to regain the English hold, a further Viking revival took place in 947 under Erik Bloodaxe, expelled as the King of Norway, but accepted as king at York. It was not a straightforward business. The Dublin and York Viking kingdoms fought one another, and there was much changing of sides.

THE POWER OF THE CHURCH

By the mid-tenth century, the church was a formidable power in the land, the wealthiest single institution, though its riches were divided among many abbeys and the bishoprics. Kings and magnates continued to make endowments. It was not as yet organized into parishes but its activities were centred on large churches or minsters, their name preserved in many place names, from where a small corps of itinerant priests served a wide area. In many places, an open-air cross served as the meeting place for religious observance.

ROUGH JUSTICE

Strongly religious as the Anglo-Saxons were by now, theirs was not a society which brought Christianity far into the practices of daily life. Violence was endemic. Free men carried weapons and were prepared to use them. Although fines and compensation payments were the most common judgements, many crimes were punishable by violent means. Floggings, branding, the slitting of noses and cropping of ears were routine minor punishments. Moneyers whose coins were of adulterated metal had a hand cut off. Hangings were frequent, drownings and beheadings were also resorted to. Imprisonment was rare and probably only employed in the case of high-ranking persons. Where a defendant's guilt was disputable, the judgement of God' was resorted to, in one of three forms. In the ordeal by water, if he floated, he was guilty (swimming was an unusual skill). Inside the church, he might be required to carry a pound weight of glowing iron for nine feet, or to take a stone out of boiling water. If the resultant injuries had not healed within three days, he was guilty. There are some signs of a more humanitarian attitude. Archbishop Wulfstan of York, drawing up laws in the time of King Cnut, wrote: 'Christian men shall not be condemned to death for all too little; but one shall determine lenient punishment for the benefit of the people, and not destroy for a little matter God's own handiwork.' King Athelstan raised the age at which a young thief might be hanged from twelve to fifteen. One social institution which the church long struggled to control was that of marriage. In the earlier centuries of the Anglo-Saxons, divorce and remarriage were easy to arrange. An early Kentish law states: 'If a freeman lie with the wife of a freeman, he shall pay ... wergild, and get another wife with his own money and bring her to the other man's home.' Such a law does not appear to set a high or independent status on the woman, but in Anglo-Saxon society a woman had greater freedom than was to be the case after the Norman Conquest. She could hold land in her own right and dispose of it as she pleased. She could appear as a compurgator (oath-taker) in court, and an eleventh-century law states that: 'No woman or maiden shall ever be forced to marry one whom she dislikes, nor be sold for money' (This of course relates only to free-born women). In fact the practice of arranged marriages, at least in property-owning families, would continue for several hundred years,

PAYING OFF THE DANE

From the early tenth century the Norsemen had established an independent state in the north of France, with its capital at Rouen. Still conscious of their Nordic origins, the Normans allowed their ports to be used by the raiders into England. This caused deep resentment and hostility in England, and in 990-91, the Pope felt compelled to mediate. The diplomatic settlement did not affect the raids, which became heavier, and Aethelred's treasury was depleted by vast sums paid to buy them off. In 1009 a new onslaught came, of Danes and Norsemen from the great war-camp at Jomsburg at the mouth of the Vistula. In 1011 they took Canterbury and Archbishop Aelfheah (St Alphege), refusing to sanction a separate ransom for himself, was killed by their troops in 1012. The Council found £48,000 from a country sliding fast towards economic ruin to pay off the invaders once more. Nine hundred years later Rudyard Kipling made the point in 'What Dane-geld Means':

... we've proved it again and again,

That if once you have paid him the Dane-geld,

You never get rid of the Dane.

Norman England

THE IMPOSITION OF NORMAN RULE

The closest parallel in history to William's invasion was that of the Romans a thousand years before: a small group imposing government on a much larger one. But much had changed in that time. His army was smaller, but he was familiar with the people, the southern part of the country, and its methods of government. His aims and his methods were quite different. The Romans needed no justification or sanction for their assumption of control; William had already secured the support of the Pope and hastened to have himself formally crowned and consecrated with the Anglo-Saxon ceremonial. Edward the Confessor's promise and Harold's oath-breaking were vital elements in Norman propaganda. The new king had no ancestral claim, and was not of any royal descent himself. His rule might have been a transient thing, lasting only his own lifetime, or less. Anglo-Saxon England became, irreversibly, Norman England.

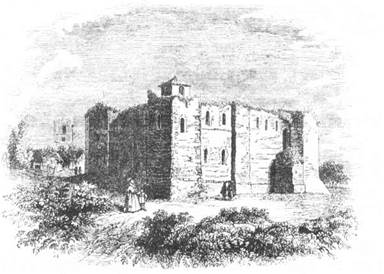

This was made possible by a combination of policy, advanced military skill, and the social system evolved by the Normans. The policy was for the king to establish his own men at all strategic places in the country. Land and wealth was what they had supported him for, and they seized their chance readily. Without delay they built castles for themselves, at first only timber structures on artificial or natural mounds, with a wooden outer fence. In time, stone castles, such as Colchester above, would replace them on an ever-more substantial scale.

The remains of Colchester Castle as they appeared in the nineteenth century. The largest Norman castle in Europe, Colchester Castle was constructed over the massive vaults of the ruined Roman Temple of Claudius.

The castle was scarcely known in England until the advent of the Normans, and such as already existed were probably built by Normans invited in by Edward the Confessor. English magnates had lived in relatively unprotected halls. From the castle, the new lord could dominate his tract of land, with his own detachment of mounted soldiers and archers to ensure his security. Like the Romans before him, William, finding the north a restive and dangerous province, carried out a campaign of devastation and terror in 1069. Even the Danelaw, always ready to acknowledge a Scandinavian overlord, did not welcome the Normans, whose speech was now Old French rather than Old Norse. The form of social organization which underlay Norman government was what later generations called the 'feudal system'. Already the structure of English society had been moving towards the concentrated power of landowners and regional magnates at the expense of the free ceorls and the lower ranks of thegns.

THE FEUDAL SYSTEM

The introduction of feudalism nevertheless made fundamental changes to English life. Up till now ownership, service, legal rights and duties had formed a confused, varied and widely overlapping pattern, reflecting local and regional traditions, obligations and arrangements that went back to the first Anglo-Saxon settlements. One writer refers to the Norman aristocracy as a 'kleptocracy', a ruling class of thieves: twenty years on from the Conquest they had emerged as owners of virtually all the land. The principles of land tenure were made clear and universal. All land was held of the king. Thus from William 1 on, the king was always the King of England, rather than (as the Anglo-Saxon monarchs had in effect been) King of the English. Under him were some six hundred tenants-in-chief. They owed the king specific military service; even if they were bishops or abbots, their own vassals would include a specified number of knights. Under them was a broadening structure of tenants and subtenants, bound in a structure of mutual obligation.

It was never a fixed and definitive system, but like all human arrangements, was adapted to individual circumstances and tended through time towards a greater complexity which ultimately began to break up through its own rigidity and the problems caused by rivals claiming the kingship. Although it worked as an economic system, with the manor and the market as the sources of production and exchange, its origin was as a military hierarchy, with a moral element firmly cemented into it.

MAINTAINING THE GRIP ON POWER

A further consequence of Norman rule was the beginning of the long involvement of England with the dynastic disputes and territorial wars fought out in France, Burgundy and the Low Countries. Later in his reign William I set the pattern of an absentee king, struggling to maintain or extend his holdings in France. After two hundred years of engagement with the Nordic powers, the crucial relationships of the Anglo-Norman state and its successors were now with the shifting power-bases and rich fiefdoms in the lands across the Channel.

The insecurity of a self-imposed monarchy, the distractions of possessions outside England, and the extreme energy and rapacity of some of his barons, like William's own half-brother Odo of Bayeux, were among the pressures that began a centralization of royal power and a series of measures that increased the king's control over events which an Anglo-Saxon king might have left to the shire-reeve or the ealdorman. Only on the outer fringes, to north and west, where they acted as defenders against Welsh and Scots, were the Norman barons set no boundaries for expansion and freed to an extent from royal control, creating the 'Marcher earldoms' and leading to the 'March law' of later centuries. Overruling all other considerations of feudal loyalty was fealty to the king. Through the royally appointed sheriffs, a solemn oath of loyalty to the king was made by the entire adult male population, twice a year.

The Great Seal of William the Conqueror William the Conqueror

HEROES AND HISTORIANS

The twelfth and thirteenth centuries were a golden age for the 'chroniclers' – part historians, part story-tellers, part propagandists – who, with access to many ancient documents now lost, and drawing on spoken accounts passed on in the oral tradition, wrote a wide range of histories, biographies, genealogies and accounts of great deeds. Ignoring the scholarly example of Bede, they were often credulous and inventive. But their concept of history was as something to show the reader a moral, or to glorify the present state by linking it to past greatness – or the opposite: to show how things had sunk down. The medieval English looked backwards with a remarkably inclusive view. The Normans had no history; but there were the great Anglo-Saxon exemplars like Athelstan and Alfred the Great. And before the Anglo-Saxons? Geoffrey of Monmouth (c.1100-55), a churchman, based for a considerable part of his life in Oxford, has been described as 'the inventor of British history. He wrote the Historia Regum Britanniae, 'History of the Kings of Britain'; claiming to have taken information from a 'very ancient book written in the British [Welsh] language'. Geoffrey gave a major role to a figure who would otherwise scarcely rate a footnote in history, King Arthur, the great hero of Britain, with his wizard-counsellor Merlin. His book marks the start of a torrent of Arthurian literature, and gives European literature (and pre-Raphaelite English painting) one of its greatest themes. He also enlarged on the myth that Britain was founded by one Brutus, a Trojan hero, escaping from the sack of Troy. Thus the English could look back with satisfaction on a splendidly heroic past going right back to the Greek epics, even though the precise connections with these early phases and figures might be shrouded in mystery.

Despite some scepticism even at the time the first copies were circulated, it was not until the sixteenth century that the facts of Geoffrey's account were seriously questioned. Polydore Vergil, an Italian humanist commissioned by Henry VII to write a history of England, which was published in 1534, caused outrage by dismissing the Brutus legend. But even two hundred years later the historical existence of Brutus and Arthur still influenced wishful thinkers.

Дата добавления: 2018-09-24; просмотров: 2008;