Century and further...

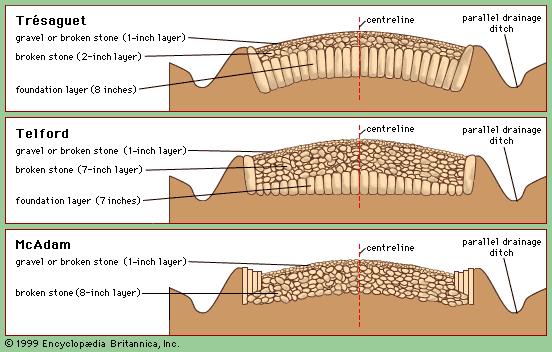

Back across the Atlantic, but later, in 18th century England, the technology of highway construction was getting a long overdue boost from two British engineers, Thomas Telford and John Loudon McAdam. Telford, originally a stonemason, built over 1,000 roads, 1,200 bridges, and numerous other structures.

|

| http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/media/19288/Cross-sections-of-three-18th-century-European-roads-as-designed |

Although his system was faster and less expensive than the Romans’ method, it was still costly and required frequent resurfacing with gravel.

On the other hand, the greatest advantages to McAdam’s system were its speed and low cost, and it was generally adopted throughout Europe.

On the other hand, the greatest advantages to McAdam’s system were its speed and low cost, and it was generally adopted throughout Europe.

During this same time period, the growth of turnpikes was resulting in much improved road conditions across England. Private individuals built roads themselves and then charged for their use, usually blocking passage by setting a long pole (pike) across the road. Once the toll had been paid, the pole would be swung (turned) out of the way, allowing the travellers access to the road (turnpike).

| http://www.polyline.ru/publications/istoriya-rossijskih-dorog |

| http://nevsepic.com.ua/art-i-risovanaya-grafika/12735-starinnye-avto-107-rabot.html |

As European settlers migrated across the Atlantic to the U.S., they found themselves faced with an almost total lack of roads – in Europe they at least had the Roman roads to use as a foundation for rebuilding. In America there were only Indian trails, and while they were long and quite extensive, they were also very narrow, allowing only for single file passage of foot traffic. Like England, went through a period of turnpike development, and for many years, turnpikes were the best roads in the U.S.

As European settlers migrated across the Atlantic to the U.S., they found themselves faced with an almost total lack of roads – in Europe they at least had the Roman roads to use as a foundation for rebuilding. In America there were only Indian trails, and while they were long and quite extensive, they were also very narrow, allowing only for single file passage of foot traffic. Like England, went through a period of turnpike development, and for many years, turnpikes were the best roads in the U.S.

Not surprisingly, the overall development of transportation in the U.S. continued in the same way as in England and interest in building and maintaining long distance roads waned during the last half of the 19th century. But the invention of the motorcar changed all that for everyone. Obviously, motorized vehicles made it possible for both people and goods to travel both more quickly and more comfortably – so long as there were adequate roads upon which they could travel. Thus the Good Roads Movement was born.

Conclusion

As they say, the rest is history – a history that most of us have experienced and just about any drive we take today provides concrete evidence of the outcome. Ironically, even at its height, American modern interstate highway system totals only about 42,500 miles (as of 1991). Granted, this figure does not include surface streets or other roads.

But 2,000 years ago the Romans, without the help of all our engineering technology or road-building machinery, constructed 53,000 miles of roads, much of which is still in use today.

I can’t help but wonder if our roads will be as impressive to historians 2,000 years from now.

Right-of-Way.

|

| http://stroitelstvo-new.ru/1/dorogi |

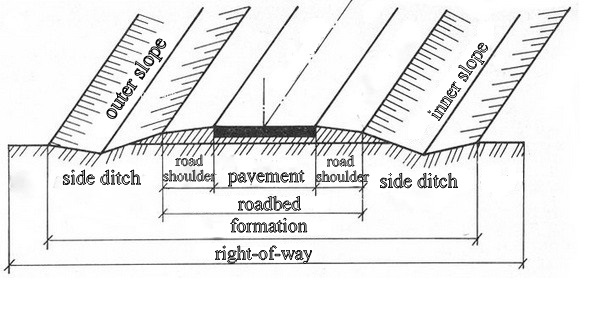

The zone which is marked to lay the road is called the road zone or right-of-way. The higher is the technical classification of the road, the wider is the right-of-way for its construction. The road zone includes such parts of a road as a carriageway, road shoulders, inner and outer slopes, and other parts.

The road surface strip within the limits of which motor vehicles run is called a carriageway. Usually it is reinforced by means of natural or artificial stone aggregates. These stone aggregates form the pavement.

The strips of the ground which adjoin the carriageway are called the road shoulders. The shoulders render lateral support to the pavement. In future the pavement will always be made of solid materials within the limits of the carriageway.

To lay the carriageway at the required level above the ground surface a formation or roadbed is constructed. It is constructed in the form of embankments or cuttings with side ditches for drainage and the diversion of water.

The formation includes borrow pits – shallow excavations from which the soil was used for filling the embankments. It also includes spoil banks. Spoil banks are heaps of excessive soil remaining after the excavation of cuttings.

The carriageway and shoulders are separated from the neighbouring land by slopes. The cuttings and side ditches have inner and outer slopes. The junction of the surface of the shoulders and the embankment slope is called the edge of the roadbed. The distance between the edges is called the width of the roadbed.

Дата добавления: 2016-03-22; просмотров: 2996;