WOMEN IN THE CITIES

Throughout the 1930s, urban life was difficult. Food, housing, and public services had long been in short supply; now, with millions coming to the cities seeking work, the shortages worsened. No government could have met the needs of all these newcomers, but Stalin’s could have done more than it did, particularly during the First Five‑Year Plan when it concentrated on building up heavy industry. So people crowded into already overcrowded apartments and dormitories, made do with limited running water, and ate plain food. Wendy Goldman has written that in 1932, “workers lived on dry rye bread and potatoes, a few seasonable vegetables (cabbage, onions, and carrots), and canned fish.” Legal peasant markets and a black market in scarce goods filled some of the gaps, but at prices higher than many people could afford. Wages fell during the First Five‑Year Plan; in 1937, they were still only 66 percent of the 1928 level. The standard of living improved somewhat in the mid‑’30s, then worsened again in the late 1930s, when the government increased military spending.15

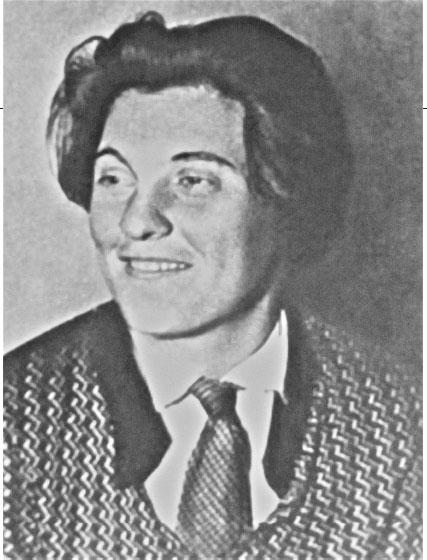

A photograph of Praskovia Angelina taken in the 1930s or 1940s.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pasha_angelina.gif. Accessed June 27, 2011.

PRASKOVIA ANGELINA

In 1948, Angelina described a babi bunt against her brigade of female tractor drivers.

“Suddenly something terrifying occurred. At the entrance to the village we were met by a crowd of agitated women. They were standing in the middle of the road and shouting all together: ‘Get out of here. We’re not going to allow women’s machines on our field! You’ll ruin our crops!’

We Komsomol [Communist youth organization] members were used to kulak hatred and resistance, but these were our own women, our fellow collective farmers! Later we became friends, of course, but that first encounter was terrible.

You can imagine what a state we were in: we had been expecting a triumphant entry and now this…. My girls were on the brink of tears, and even I, normally quite feisty, didn’t know what to do. The women surrounded us in a tight circle, yelling, ‘One inch more, and we’ll tear your hair out by the braids and kick you out of here!’

[After they fetched a local communist official, the crowd dispersed and they began plowing.]

The festive mood was gone, of course. The girls’ faces were sweaty and angry. We felt like we were on a battlefield: one mistake and you’re dead.”

SOURCE: SHEILA FITZPATRICK AND YURI SLEZKINE, EDS., IN THE SHADOW OF REVOLUTION: LIFE STORIES OF RUSSIAN WOMEN FROM 1917 TO THE SECOND WORLD WAR (PRINCETON: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2000), 313–14.

In the cities, as in the countryside, there were women who benefited from the Soviet system. Pasha Angelina had an urban counterpart in Valentina Bogdan, the daughter of a working‑class family who traveled with friends to the city of Krasnodar in 1929 to take entrance examinations for the Institute of the Food Industry. Years later she remembered her feelings: “More than anything in the world, we wanted to enter [the institute] and join the elect. I said half‑jokingly: ‘Girls, let’s pray to the institute, asking it to admit us.’ We waited until nobody was around and then raised our arms and said loudly, in unison, ‘Admit us within your walls. Admit us! Admit us!’”16

Bogdan was one of the millions of young, poor women who were admitted. By 1939, 56 percent of the students enrolled in secondary schools in the Russian republic of the Soviet Union were girls, as were 50 percent of the students in higher education.17 These remarkable statistics would have delighted the pre‑revolutionary feminists. Furthermore, the government constantly declared that workers and peasants were the favored classes in the Soviet Union, and backed up those declarations by giving preferential treatment to such people. It also proclaimed that Soviet women were men’s equals and that they should improve themselves for their own sakes as well as for the public good. Lower‑class women such as Bogdan and Angelina had reason to hope, therefore, that they could, through personal effort, earn better lives for themselves among the “elect.”

The “elect” they sought to join was composed of families, most of them from the middling and lower ranks of pre‑revolutionary society, whose adult members worked in the leadership of the party, government, industry, and the military. These people were allocated comfortable apartments, had access to better‑staffed and equipped medical clinics, sent their children to the best schools, and rode around in government‑issued cars. They could afford to hire servants and buy the consumer goods that were available. Galina Shtange, the wife of an engineering professor, recorded in her diary in 1936 a glowing report on beautiful new stores in Moscow and concluded, “When you recall the first years after the revolution and the way things were back then, it’s just exhilarating to think that all this has been achieved in just 20 years.” Fruma Treivas, the wife of an editor at the party newspaper Pravda, wrote her memoirs years later, by which time she was more aware than Shtange of the differences between the elite and the rest of Soviet society in the 1930s. “We were so far removed from the lives of ordinary people that we thought this was the way it should be,” she remembered. “The way I looked at it, Vasilkovsky [her husband] was killing himself working long hours at an important job, all for the glory of the motherland and Stalin.”18 Among the Stalinist elite, hard work and dedication legitimated privilege.

Дата добавления: 2016-01-29; просмотров: 1222;