Extraordinary Women in Troubled Times

The history of Muscovy is pockmarked by upheavals. The worst of these was the Time of Troubles (1598–1613), a period of political and economic instability that climaxed in a vicious civil war. A much shorter and less catastrophic uprising occurred in the 1670s when a former slave, Stenka Razin, led an army of Cossacks, peasants, and urban poor up the Volga in an attempt to overthrow the government. Even as Razin’s army surged along the river, moreover, a religious dispute was producing fiery confrontations between tsarist officials and defiant members of a new sect called the Old Believers. In all these conflicts, a few women played leading parts.

It had long been common across Europe for women to join in riots, rebellions, and wars. Muscovy was no exception to this rule. In Pskov in 1581, townswomen defended the city against Polish troops by firing artillery at the attackers, pelting them with rocks, and finally, in the words of a chronicler, “hurl[ing] themselves against the remaining enemy troops in the tower, fighting with all the arms given them by God.” Women also joined Stenka Razin’s revolt. Most did the chores usually assigned to women by armies: they cooked and nursed the sick and injured. A few also fought. The most famous of the female warriors was Alena Arzamasskaia, a nun from the town of Arzamas east of Moscow, who ran away from her convent in 1669 and, dressed like a man, led a unit in Razin’s army. Her fate echoes that of a more famous female soldier, Joan of Arc: she was captured, tortured, convicted of being a bandit and impersonating a man, and burned on a pyre. Practicing witchcraft did not condemn one to death by fire in Muscovy, but participating in a major uprising against the tsar did.35

In the politics of the elite during Muscovy’s warring times, women took the traditional parts of advisers, promoters of the fortunes of their menfolk, and pawns. Of the handful of women prominent enough to make it into the accounts of observers and participants, two deserve special mention, one because she was a pawn of unusual resourcefulness and the other because she was a founder of the largest schismatic movement in Russian history.

MARFA NAGAIA (c. 1560–1610)

Deeply involved in politics during the Time of Troubles were three tsaritsy: Irina Godunova, wife of the Tsar Fedor and sister of Boris Godunov, the regent from 1584 to 1598 and tsar from 1598 to 1605; Maria Godunova, Boris’s wife; and Marfa, the last wife of Ivan IV. Of the three, Marfa had to be the most adroit, because her situation was the most perilous. She relied on the rooted reverence for royal women and also on her own political skills to navigate the troubled waters she first entered when, as a girl named Maria, she married Ivan the Terrible.

That marriage went better than she might have expected, given Ivan’s predilection for disposing of his wives. Maria was his seventh; he had exiled two of her predecessors and was rumored to have poisoned three. His first wife may have been poisoned by others. Maria managed to outlive her murderous husband, but when he died in 1584, he left her in an uncertain situation. Their marriage violated church law, which permitted only three marriages in a lifetime, so Maria was not legally tsaritsa in the eyes of the church, and her son Dmitri had a questionable claim to the throne. Godunov, the regent, decided to exile the problematic mother and son to Uglich, a town far from Moscow and its court politics. In 1591, Dmitri suddenly died. Godunov sent investigators to determine the cause of death; they reported back the unlikely tale that the boy had accidentally cut his own throat. When Tsaritsa Maria protested that her son had been poisoned on Godunov’s orders, the regent commanded her to become a nun. Upon taking her vows, Maria became the nun Marfa. Seven years later, Tsar Fedor died without heirs and Godunov became tsar.

Marfa was living in a remote convent when, in 1603, a Muscovite soldier named Grigori Otrepev popped up in Poland claiming to be her dead son. He gathered an army, and in 1605, shortly after Godunov died, seized Moscow and was crowned Tsar Dmitri. To validate his claim, the new tsar sent for Marfa. She came to Moscow and publicly swore that Otrepev was her long‑lost son. Isaac Massa, a Dutchman then living in Moscow, understood her reasons for lying. “It was not surprising that she recognized Dmitri as her son, even though she knew full well that he was not. She lost nothing thereby; on the contrary, she was thereafter considered a tsarina, treated magnificently, and led to the Kremlin, where she was given the convent of the Ascension as her residence. There she lived as a sovereign.”36

When a boyar group led by Vasili Shuiskii overthrew Otrepev in 1606, Marfa had to change her story. Now she announced that her son had actually died years before and that she had been forced to swear that the pretender was Dmitri. “She said she had merely acted out of fear,” Massa reported, “and in her joy at her deliverance from her sad prison [the remote convent to which Godunov had banished her], she had not known what she was doing.” Shuiskii soon had the corpse of the real Dmitri brought to Moscow so that he could hold a public viewing to establish once and for all that the boy was dead. Again Marfa took her place onstage. In front of a crowd presided over by church and government officials, she looked into the coffin and declared, in awed and prayerful tones, that her son’s body lay there, as fresh as it had been on that sorrowful day fifteen years before when she had laid him to rest. Christians believed that holy people did not decay after they died. So Marfa was testifying that Dmitri had graduated into sainthood. Massa, who attended this ceremony, was no more taken in by it than he had been by Marfa’s certification of Otrepev. He noted that only Marfa and a very few of the highest‑ranking clergy were permitted to view the blessed remains.37

Marfa’s career as Dmitri‑checker was not yet over. A few years later another False Dmitri knocked at her door. She again agreed to testify that her boy was back. Marfa was spared another staged renunciation, because she died in 1610, before the Second False Dmitri was overthrown and a new dynasty, the Romanovs, came to power.

Years later, another Marfa, this one the mother of Tsar Michael Romanov, donated money for the perpetual saying of prayers for Marfa’s soul. It was not unusual for the mother of a tsar to so honor another, but Romanova may also have been motivated by sympathy for Marfa. Romanova had also been forced to become a nun by Boris Godunov, because her husband Fedor had lost a round in the power struggles of the Time of Troubles. She too had lived in remote monasteries, under orders never to return home and from time to time in fear for her life and that of her son Michael, who lived with her. She could understand why Marfa had told so many lies, and perhaps she thought a few extra prayers would help her soul avoid damnation.38

FEODOSIA MOROZOVA (1632–75)

Fifty years after Marfa’s death, Feodosia Morozova became a leader of a schism that permanently split the Russian Orthodox Church and created a new sect, the Old Believers, that continues to this day. The dispute that gave rise to this rupture began in the 1650s when church leaders ordered revisions in the liturgy. The proposed changes, which included using a different number of fingers when making the sign of the cross, introducing a new spelling of Jesus’ name, and some editing of church interpretations of Christian doctrine, seem innocuous today. Seventeenth‑century Muscovites, however, considered them to violate the correct practice of Christianity. The church leaders who ordered the changes believed that they were removing errors that had crept in because the Turkish conquest of Byzantium had diminished contact between Muscovy and the centers of the Orthodox faith in Greece. Unfortunately, many Muscovites, lay and clerical, disagreed. They believed in the sanctity of the uncorrected practices and became convinced that the Devil was behind the revisions. Soon a charismatic priest, Avvakum, began to speak against the reforms, and long‑standing discontent with the religious leadership in Moscow began to coalesce into rebellion.

Georg Michels has found that “women formed a strong numerical majority among early Old Believers” and that the work of its first female converts was “absolutely crucial to the formation and survival of early Old Belief.” His words remind us of the equally important role played by women in Christianity’s establishment among the Rus. In both eras, the Kievan and the Muscovite, the earliest and most influential female converts, in the first case to a new faith, in the second to a sect within that faith, came from the wealthier households.

To join the new sect was to rebel not only against the church, but against the tsar. Alexis reacted by demanding recantation. Some women returned to the fold; others defied him. Two abbesses, Elena Khrushcheva and another whose name has survived only as Marfa, made the Moscow convents they headed into bastions of the new sect. After the authorities fired Khrushcheva from her position, she traveled around Muscovy proselytizing. She found shelter with wealthy widows who were promoting Old Belief among their peasants. One of the most rebellious of these widows was Evdokia Naryshkina, the aunt of the Tsar Alexis’s second wife. When, in the 1670s, the tsar sent guards to confine her in her house, Naryshkina rushed at the commander of the detachment and grabbed hold of his beard, thereby gravely insulting his honor. Later she escaped captivity by leading her family across a swamp. The group remained at large in a forest encampment until the tsar’s soldiers tracked them down in 1681.39

The best known of the early Old Believer women was Feodosia Morozova. She became one of the heroines of Russian history, praised in pamphlets written shortly after her death, hailed as a rebel by nineteenth‑century revolutionaries, and honored as a holy martyr by Old Believers to this day. There was little in her early life that foreshadowed such a heroic biography. Morozova was born into one boyar family, the Sokovnins, and married into another, the very rich, very prominent Morozovs. She enjoyed a happy, albeit short, marriage with her husband Gleb, with whom she had one son, Ivan. In 1662, Gleb died and Morozova took charge of their extensive properties. “She may have owned eight thousand serfs and had three hundred slaves in her household in Moscow alone,” Margaret Ziolkowski writes. Morozova supervised all these people from luxurious rooms overlooking gardens where peacocks roosted in the trees. She took particular interest in the piety of the peasants on her estates, ordering priests to make sure their parishioners attended church regularly.40

In the early 1660s, Morozova began to criticize the reforms in Orthodoxy. When the Old Believer priest Avvakum returned from exile to Moscow in the mid‑1660s, she invited him and his family to stay with her. Soon Morozova was taking in other schismatics and speaking out in opposition to the tsar. Alexis confiscated some of her estates in punishment, but he also attempted to conciliate her, perhaps because Morozova was lady‑in‑waiting to his wife, Tsaritsa Maria. At first Morozova appears to have wavered in her support for the schismatic movement, but as the years passed she grew more determined. She converted her sister Evdokia to the cause and enlisted the covert support of her brothers. In 1670 she secretly became an Old Believer nun.

Convinced that she was doing God’s will by defending the old practices, Morozova was willing to martyr herself and her loved ones. When her uncle urged her to consider the welfare of her son, who was at mortal risk because of her behavior, she replied, “If you wish, take my son, Ivan, to Red Square and give him over to be torn to pieces by dogs and try to frighten me. Even then I will not do it [accept the reforms]…. Know for certain that if I remain in the faith of Christ to the end and am fit to taste death for the sake of this, then no one can steal him from my hands.”41 Ivan subsequently died, perhaps murdered, and Morozova grieved for him, but she did not regret her decision, for she believed she had chosen the righteous path. God would restore her son to her in heaven.

Nor was Morozova intimidated by the powers arrayed against her. Contemporary accounts detail her self‑righteous and insulting behavior toward top churchmen. She is reported to have told a group of interrogators, “It is fitting, there where your liturgy is proclaimed [during church services], to engage in a necessary function and to vacate the bowel–that’s what I think of your ritual.” She was only slightly more polite to the tsar, to whom she wrote in 1670, “It does not befit the sovereign to harass me, poor servant that I am, because it is impossible for me ever to renounce our Orthodox faith that has been confirmed by seven ecumenical councils. I have often told him about this before.”42

By this point, Morozova was courting martyrdom. In 1671 she finally exhausted Alexis’s patience by refusing to attend his wedding to his second wife, Natalia Naryshkina. (Morozova’s protector, Tsaritsa Maria, had died.) Tired of Morozova’s obstreperousness and wanting to send a message to her fellow schismatics, Alexis ordered her arrested, along with her sister Evdokia and another female supporter, Maria Danilova. The three women were held in the Novodevichy convent in Moscow, where many boyar women visited them to express support.43 The tsar then exiled the three to more distant convents, even while continuing to offer them clemency on the condition that they accept the reforms. They refused. Finally, in the fall of 1675, incarcerated in a deep pit far outside Moscow, Morozova, her sister, and their friend died of starvation.

Morozova was not the only Old Believer martyr. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of members of the sect emulated the fate of their hero, Avvakum, who was burned at the stake in 1682. When threatened with arrest, they gathered in groups and set themselves on fire. After decades of intermittent, violent confrontation between the authorities and the schismatics, the conflict subsided. The Old Believers became a permanent sect within Russian Orthodoxy, officially outlawed but persisting. The faith endures to this day inside and outside Russia, women’s contributions to its survival continue, and Morozova remains a revered figure in its pantheon.

She was a most remarkable woman. Not only did she refuse to submit to the formidable powers arrayed against her, but she also worked to develop the theology of Old Belief. “Feodosia was assiduous in the reading of books,” Avvakum wrote, “and derived a depth of understanding from the source of evangelical and apostolic discourses.” She argued matters of faith forcefully with the church leaders sent to question her and also with other Old Believers, including the egotistical Avvakum. Even more remarkably for a Muscovite woman, she wrote religious tracts. After her death, Avvakum praised her intellectual fortitude: “When the time came, Feodosia put aside feminine weakness and took up masculine wisdom.”44 She was manly in her intellect, he wrote, and in her resistance to the authorities. That Morozova had transcended the supposed limitations of her gender was the highest praise Avvakum could bestow on her.

The history of Christianity is full of women rebelling against state and church authorities in defense of their understanding of the faith. Perhaps one explanation of this phenomenon is that religion was virtually the only source of power and authority through which women could hope to stand on an equal footing with men. Most female saints were women who had resisted the pressure of evil officials and unsympathetic families, willingly gone to horrible deaths, and then reportedly ascended to heaven to live with God. Some of these martyrs, for example the Muscovite favorite St. Paraskeva, patron saint of married women and housework, were as defiant and assertive as Morozova. The tales of all these female religious rebels inspired women across Europe to join heretical movements in the medieval period and to break with Catholicism altogether during the Reformation. Some of the new Protestant sects of Central and Western Europe were as dependent on the support of prosperous women as were the Old Believers in Russia. Morozova was probably ignorant of the Anabaptists and the Quakers, among whom women figured as founders, but she undoubtedly was versed in the hagiography of the early Christian female martyrs.

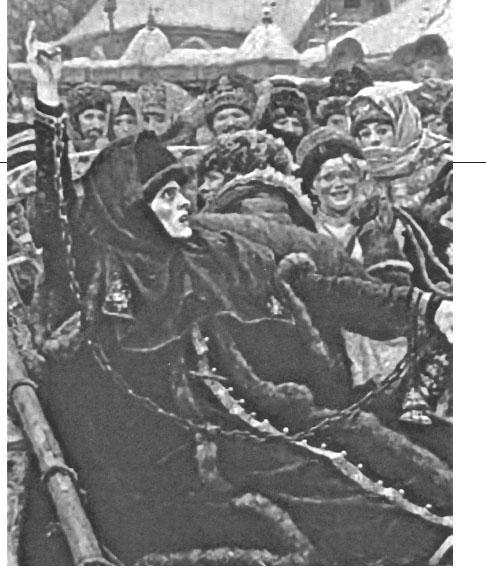

Feodosia Morozova as imagined by the nineteenth‑century painter Vasili Surikov.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Boyarynja_Morozova.jpg. Accessed June 27, 2011.

FEODOSIA MOROZOVA

In 1669, Morozova was at odds with Avvakum’s sons, Ivan and Prokofii. Warned by Avvakum that “it will go badly for you [unless you]… make peace with my children,” Morozova wrote to Avvakum’s wife, Anastasia. After repeating her charges against the sons, she concluded:

“Little mother, I have sent you fifteen roubles for whatever need you may have, and I sent eight roubles to the little father [Avvakum]: two for the little father alone and six for him to share with Christ’s fraternity. Write to me whether it gets to them. And from now on don’t allow your children to read others’ letters, make them swear that from now on they won’t read my letters and the little father’s. Christ knows that I am as happy with you as with my own birth mother. I remember your spiritual love, how you visited me and nourished my soul with spiritual food. Formerly you really were happy with me and I with you, and truly I am as happy as before. But your children have turned out to be real spiritual enemies of mine….

Forgive me, a sinner, little mother, you and Ivan and Prokofii, in word, deed, and thought, for however I have grieved you. Ivan and Prokofii, you have greatly grieved and vexed me, because you wrote against me and others to your father…. Forgive me, my beloved mother, pray for me, a sinner, and for my son. I beseech your blessing.”

SOURCE: MARGARET ZIOLKOWSKI, ED., TALE o F Bo IARy NIA Mo Ro Zo VA: A SEVENTEENTH‑CENTURY RELIGIOUS LIFE (LANHAM, MASS.: LEXINGTON, 2000), 89–90. REPRINTED BY PERMISSION OF ROMAN AND LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHING GROUP.

She probably took inspiration also from Muscovite customs that permitted women to express their piety outside the confines of the family and the convent. It was common for Muscovite women, peasants as well as nobles, to go on pilgrimages to the shrines of saints. A few became “holy fools” who traveled and preached from village to village. Some devotees of St. Paraskeva got together on Fridays to parade through their communities, singing the saint’s praises and calling on other women to quit their work and join them. The church was suspicious of this kind of spontaneous, unregulated religiosity. In 1551, delegates to a church conference complained, “False prophets, men and women and maidens and old grannies wander among parishes…, naked and barefoot, with loose hair and dissolute, shaking and beating themselves.”45 The Muscovite church was too loosely organized to repress the grannies, and so the shaking and beating continued, helping to pave the way for later conversions to Old Belief.

Morozova was inspired by the female saints; she was empowered by her rank. Because she was a boyarina, she could turn her home into a center of schismatic activity and build her authority as a leader of the movement. Her status emboldened her to defy the tsar; she knew that he would hesitate to strike down a woman from a leading family. Her sense of her own authority also empowered her to lecture Avvakum, which roused class and gender resentments in the priest. Angrily he wrote to her, “Are you better than we because you are a boyar woman?… Moon and sun shine equally for everybody… and our Lord has not given any orders to earth and water to serve you more and men less.”46 Avvakum kept telling her over the years that she should submit to him because he was a man and a priest. He had to repeat these orders because she continued to assert herself.

All the Old Believer women, lay and clerical, risked social ostracism at best, death at worst. It was no small thing in Muscovy to refuse to obey the tsar and the priests, especially if one was a woman. So the great majority of women did not do it. Instead, they remained within the established faith and were probably horrified by the rebellion. When they heard about Naryshkina pulling her jailer’s beard or Morozova refusing to obey the tsar, they must have wondered how these women could so dishonor themselves. Who would ever speak to them again? Who would marry their daughters? Some devil must have possessed them. Otherwise they could not have forgotten that honor lay in being modest, stay‑at‑home, dutiful mistresses.

And yet, among the horrified majority there may also have been a few who admired the defiance of the Old Believer women. For discontent about the restrictions on elite women was spreading in Moscow by the time of the schism. Perhaps it helped to fuel the schism. After the death of Alexis in 1676, it certainly affected Muscovy’s politics at the highest levels.

Kremlin Women

CHANGE IN THE WEST

This desire for change arose among the highest‑ranking Muscovite women. By the last decades of the seventeenth century, some of them had learned that they were more confined than elite women elsewhere. They came by this information from tales spread by foreigners living in Moscow as well as from imported books. Their enlightenment was part of a larger exchange between Muscovy and Central and Western Europe, ongoing throughout the seventeenth century, that accelerated under Tsar Alexis.

Muscovites had always traded with merchants from the west, as had the Rus before them. By the seventeenth century, those merchants were coming from a region that was being transformed by political, economic, and cultural change. Centralized, bureaucratized monarchies had developed. Merchant capitalism, backed by the monarchs, was producing manufactured goods and expanding international trade. Intellectual life, which had flourished since the twelfth‑century development of the universities and court patronage of the humanities, bloomed into the Renaissance in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, leading to major scientific discoveries and promoting formal education. Technology was also advancing: artillery and primitive rifles were revolutionizing warfare, while the printing press permitted the dissemination of new ideas to an increasingly literate elite, among whom middle‑class people figured prominently. The Reformation, even while producing major wars and witchcraft persecutions, promoted literacy as well as critical examinations of Christian doctrine by clerics and lay people alike.

These developments are the reasons why historians see the medieval phase of European history as ending in the fifteenth century and the early modern period beginning in the sixteenth. The intellectual, economic, and political currents spread into eastern Europe, affecting first those areas long in contact with the West, such as Poland and Bohemia, and then lapping at the gates of Muscovy. Tsars Michael and Alexis knew that the other Europeans had more effective armies than theirs, so they brought in foreign military advisers to teach the new weapons and methods to their troops. They and their courtiers also bought the latest luxury goods, including fine textiles and ingeniously automated clocks, from merchants come to Moscow. And they listened to stories about life among royals elsewhere. They heard that queens and countesses did not spend their lives cooped up in their houses, that they rode unveiled around their capital cities, that they wore beautiful, light, brightly colored silk dresses to elegant parties, where they danced with men they were not married to.

Although he presented himself as a pious traditionalist, Tsar Alexis was willing to bend the rules governing royal women. He was an unusually attentive father to his six daughters–Evdokia, Marfa, Sophia, Ekaterina, Maria, and Feodosia.47 He expected them to be politically informed, and when away on military campaigns he sent them detailed reports.48 He also took the unprecedented step of permitting his third daughter, Sophia, to study with his sons’ tutor, an erudite monk named Simeon Polotskii. And he chose as his second wife a young woman who had experienced, by Muscovite standards, a permissive upbringing. The tsar’s open‑mindedness enabled Sophia, his daughter, and Natalia, his wife, to become important political actors.

NATALIA NARYSHKINA (1651–94) AND SOPHIA ROMANOVA (1657–1704)

Natalia Naryshkina was the niece of Evdokia Naryshkina, the Old Believer who had lived in the woods rather than submit to the tsar. The Naryshkins were one of the liberal families: they studied foreign languages, entertained foreign visitors, decorated their homes with imported luxuries, and allowed their daughters to learn to read. They also permitted them to socialize more freely than Domostroi custom would permit. When they decided, in 1670, to send Natalia to live in Moscow, they put her under the supervision of another liberal family, the Matveevs. Artamon Matveev, the family head, was a close adviser to the tsar. Alexis was now a widower, for his wife Maria had died in 1669, and when Matveev introduced his new ward to the monarch, Alexis was delighted by her outgoing ways. In January 1671 they married and on May 30, 1672, Tsaritsa Natalia gave birth to a son, who was christened Peter.

A contemporary portrait of Sophia in royal regalia.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sophia_Alekseyevna_hermitage.jpg. Accessed June 27, 2011.

SOPHIA

Dressed in clothes like these, Sophia presided over ceremonial events at court. The Swedish ambassador, Kersten Gullenstierna, described being received by her in 1684:

“Sofia was seated on her royal throne which was studded with diamonds, wearing a crown adorned with pearls, a cloak of gold‑threaded samite lined with sables, and next to the sables was an edging of lace. And the sovereign lady was attended by ladies‑in‑waiting, two on each side of the throne… and by female dwarves wearing embroidered sables and gold sable‑lined cloaks. And the lady was also attended in the chamber by several courtiers and at the sides there also stood Prince Vasily Vasilevich Golitsyn and Ivan Mikhailovich Miloslavsky.”

SOURCE: E. LERMONTOVA, SAMODERZHAVIE TSAREVNY SOFI ALEKSEEVNY, PO NEIZDANNYM DOKUMENTAM (IZ PEREPISKI, VOZBUZHDENNOI GRAFOM PANINYM) (ST. PETERSBURG, 1912), 44; QUOTED BY LINDSEY HUGHES IN SOPHIA, REGENT OF RUSSIA, 1657–1704 (NEW HAVEN: YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS, 1990), 189.

Surviving accounts do not reveal how well Natalia got along with her many stepdaughters, but they indicate that she brightened life in the Kremlin. Jacob Reutenfels, a German living in Moscow, wrote of the new tsaritsa, “She is evidently inclined to tread another path to a freer way of life since, being of strong character and lively disposition, she tries bravely to spread gaiety everywhere.” Alexis entertained his young wife by opening a theater, where plays on Biblical and classical themes were performed. This was an audacious innovation, for the church disapproved of playacting and thought still less of pagan mythology. The royal family also traveled more often than in the past to its various estates. A particular favorite was a model farm at Izmailovo where the tsar experimented with windmills and glassblowing, while the ladies interested themselves in the gardens.49

This idyllic period lasted only five years. In 1676 Alexis died at age forty‑seven. His fourteen‑year‑old son Fedor succeeded him and, despite his youth and chronically poor health, managed to carry out his duties competently until 1682, when he too died. The royal family was plunged into crisis. There were two Romanov heirs, Ivan, the fourteen‑year‑old son of Maria, and Peter, the ten‑year‑old son of Natalia. Ivan, the rightful heir, was physically and mentally disabled. Peter was healthy, strong, and precocious, so it seemed reasonable to some in the Kremlin to proclaim him tsar.

The choice outraged the streltsy, units of the standing army that were already unhappy because the government was not paying them on time and was extending their terms of service on the frontiers. It is not known whether anyone from the royal family helped to foment rebellion among the streltsy. What is certain is that some of the soldiers mutinied after the announcement of Peter’s elevation. Gangs of streltsy rampaged through Moscow, attacking those who supported Peter and murdering several of Natalia Naryshkina’s relatives.

Sophia, the educated tsarevna, stepped forward to lead the peacemaking and promote her own political fortunes. She played a major part in the negotiations that resolved the conflict, calming angry delegations of armed men and on at least a few occasions saving people from execution. Peace was restored by making concessions to the soldiers and declaring Ivan and Peter co‑rulers. Thereafter, throughout the summer and fall of 1682, Sophia was involved in consolidating a new ruling coalition based on her mother’s family, the Miloslavskiis. From this politicking she emerged, at the age of twenty‑five, as regent for her younger brothers, even though there was no basis in tradition for an elder sister to assume that position. The surviving tsaritsa, Natalia, was entitled to become regent, but her family had been decimated by the streltsy attacks, leaving her without powerful supporters at court. So she retreated with her son Peter to estates outside Moscow, while her stepdaughter gathered the reins of power.

The ambition and audacity of Tsarevna Sophia are astonishing. Nor only did she have no right to become regent, she was supposed to live her life out of public view. Tsarevny occupied lavish quarters within the woman’s section of the Kremlin, they owned estates outside of Moscow, and they controlled their private incomes and household staffs. Their good works included attending church services, patronizing the church, donating to charities, and embroidering icon cloths. In short, they had the privileges and obligations of all wealthy women, with the enormous exception that they were never to be wives or mothers.

Sophia decided to do otherwise, ruling Muscovy from 1682 to 1689 and ably continuing her father’s foreign and domestic policies. Assisted by a skilled diplomat, Vasili Golitsyn, Sophia negotiated a treaty with Poland in 1686 that gained Muscovy territory in Ukraine, including Kiev. By affiliating Russia with the Holy League, an anti‑Turkish alliance of Poland, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Venetian Republic, Sophia broke down some of her government’s hostility toward its neighbors, thereby laying the foundation for the diplomacy of Peter I. She also fostered the continuing development of art and architecture in Moscow.50

While exercising a tsar’s power, Sophia presented herself to her courtiers and subjects as a pious, righteous tsarevna. She continued to live in the women’s quarters of the Kremlin, went to church regularly, and donated generously to convents, especially the Novodevichy in Moscow. She did not marry, though she may have had a romantic relationship with Golitsyn. She also held court, in a manner befitting a tsar, not a tsarevna.

Sophia liked ruling Muscovy, and as the years passed, she sought ways to institutionalize her position. After the 1686 treaty with Poland she claimed the title “autocrat,” formerly reserved for male rulers, and ordered coins decorated with her image. In 1687 her supporters began circulating a proposal to have her crowned co‑ruler with Ivan and Peter. Portraits portrayed her wearing a crown and ermine‑collared robe, or holding the symbols of sovereignty, the orb and scepter. Court poets sang her praises. She went no further than this, for fear of alienating her brothers and powerful boyars.51 Perhaps she was also deterred by the fact that Golitsyn, whom she sent off to war in Ukraine, did not win victories that would have bolstered her reputation. When he returned from a second campaign in the summer of 1689, Sophia’s regency suddenly ended.

The dramatic events of August 1689 are well documented. Sophia hoped to glorify her adviser as a great conqueror, though the fact that he had mostly led his army on fruitless marches was well known. To that end, she expected that her seventeen‑year‑old half‑brother Peter would perform the usual ceremonies welcoming Golitsyn back from the war. Peter, at the urging of his advisers, refused. Sophia demanded that he do so, rumors began flying that she intended to arrest Peter, the younger tsar fled to the sanctuary of a monastery, and in the stand‑off that followed, Sophia’s supporters deserted her. On September 7 Peter ordered the tsarevna stripped of her title “autocrat” and remanded to the Novodevichy Convent. Her ruling days were over.

No woman could have kept power once a legitimate, healthy tsar was old enough to challenge her. Sophia managed as long as she did because she possessed extraordinary political skills and because Peter was an immature teenager. Having ordered her to spend the rest of her life in comfortable confinement, her half‑brother left her alone. Then, in 1698, the streltsy revolted again. Peter suspected that Sophia was involved, even though investigations turned up no evidence to prove it. After an angry meeting at which he accused her of treason and she denied the charges, Peter imposed on Sophia the time‑honored punishment of disgraced royal women–taking the veil. She became the nun Susanna. To remind her of the importance of loyalty to him, Peter ordered that the bodies of three of the streltsy conspirators be hanged outside the tower in which she lived. There the corpses dangled through the winter. The tsar also issued instructions limiting the number of visits Sophia could have with her sisters. His one‑time regent lived out her life in the beautiful precincts of Novodevichy, died there in July 1704, and was buried in the convent grounds.

And what of Natalia, Peter’s mother, the effervescent tsaritsa who had stepped aside when Sophia made herself regent? From 1672 onward, Natalia lived with her son at the royal estate at Preobrazhenskoe, managing the household and avoiding politics. She did not subject Peter to the confinement and supervision imposed upon young tsars who lived in the Kremlin, and so the boy played war games using live ammunition, frolicked with foreigners, and studied occasionally, when his tutor was sober enough to teach him. There is little evidence that he spent much time with his mother. Natalia did arrange his marriage when he was seventeen. Curiously, she chose Evdokia Lopukhina, the daughter of a conservative noble family. Evdokia had been brought up in seclusion, so she and Peter were ill suited to one another. One wonders why Natalia, once an outgoing young woman, should have selected a retiring maiden for her rambunctious son. The tsaritsa died in 1694 and so did not live to see her boy abolish the seclusion of elite women.

Conclusions

The lives of women in the Muscovite era, like those of earlier periods, were shaped by the politics and economics of their times. The strengthening of the central government produced warfare that made more difficult the lives of some women. The establishment of serfdom legalized the subjugation of the peasantry. The tsars’ empire‑building had devastating consequences for many native women in Siberia and brought women from scores of different ethnic groups under Muscovite rule and into contact, however remote, with Muscovite moral and social norms. The tsars also increased contacts with the rest of Europe, which led, by the reign of Alexis, to an easing of the seclusion of elite women.

Amid the instabilities fostered by these changes, gender norms held firm for most of the women of Muscovy. The elite values of the time were summed up by the author of The Domostroi, who promoted the notion that an ideal family was one in which everyone knew her or his place and all worked together to meet their material and spiritual needs. Muscovites extended these ideals to society as a whole, seeing the tsar and tsaritsa as master and mistress of the realm, presiding over a gigantic household in which the powerful took care of the needy, men guided and protected women, women served and cared for their families, and all obeyed those above them. This vision legitimated the ground rules by which women lived their lives. As in the Rus centuries, the rules empowered older women, particularly elite ones, even as they sustained boundaries beyond which women trespassed at their peril. By the end of the Muscovite period, a few women were pushing against those boundaries. The age of The Domostroi was drawing to a close.

Дата добавления: 2016-01-29; просмотров: 1597;