DEGENERATIVE DISORDERS

The brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves consist of billions of nerve cells. Each of these cells is a complex electrical and chemical transmitter that carries signals to make the muscles move and to relay information throughout the nervous system. If a few cells die or malfunction, the person will notice any change. When there is progressive deterioration in any part of the nervous system, the person gradually will lose some ability to function. This loss can involve mental ability, muscular movement, muscular control, or impaired coordination. Compared with many other diseases, the degenerative disorders are less well understood.

Alzheimer's Disease. This disease is due to a degeneration of brain cells. It gradually produces abnormalities in certain areas of the brain. The brain cells of persons with Alzheimer's disease have characteristic features that were first described in 1907 by Alios Alzheimer. The cause of Alzheimer's disease, however, is unknown. Among the several possible causes are genetic factors, toxic exposures, abnormal protein production, viruses, and neurochemical abnormalities.

The symptoms of Alzheimer's disease are gradual loss of memory and inability to learn new information, growing tendency to repeat oneself, slow disintegration of personality, increasing irritability, and depression. No effective treatment exists. Some medications modify the symptoms of the disease. Occasionally, mild sedatives, antidepressants, or antipsychotic medications may be necessary to control behavior.

Parkinson's disease was first described by Englishman James Parkinson in 1817. It is progressive degeneration of nerve cells in the part of the brain that controls muscle movements. The signs and symptoms of Parkinson's disease are shaking at rest (rest tremor), stiffness or rigidity of limbs, slow, soft, monotone voice, and difficulty in maintaining balance.

The cause of this disease remains unknown. Parkinson's disease ordinarily starts in middle or late life and develops very slowly. Many individuals with Parkinson's disease have depression. Some degree of mental deterioration occurs in about one-third of those persons with Parkinson's disease. In the later stages, auditory and visual hallucinations may develop.

In early stages of the illness, the person may not require therapy. Medication normally is introduced at a time when Parkinson's disease interferes with daily activities. The main goal of treatment is to reverse the problems with walking, movement, and tremors.

Multiple sclerosis is characterized by numbness, weakness, or paralysis in one or more limbs, impaired vision with pain during movement in one eye, tremor, lack of coordination, and rapid, involuntary eye movement. Its cause is unknown, but medical research is very active. The presence of a virus, in either immune cells or sheath-producing cells, is one suspected cause. Attacks ordinarily recur and the symptoms may increase in severity. Many persons with multiple sclerosis are ambulatory, and many are employed even after having multiple sclerosis for 20 years.

There is no cure for multiple sclerosis. Medications vary depending on the symptoms. Baclofen is sometimes useful for suppressing muscle spasticity. For severe attacks, corticosteroid drugs may be prescribed to reduce inflammation and provide temporary relief.

EYE

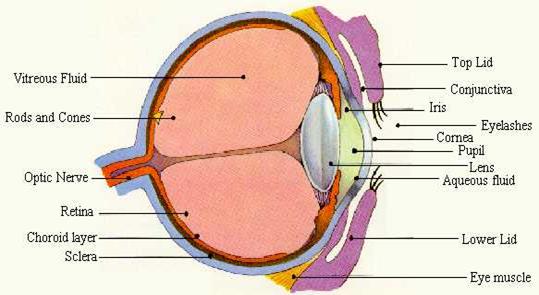

The eyes are unique instruments, able to receive definite information about the world outside our body. Thousands of times a day, the eyes move and focus on images near and far. The structure of the eye is very complex. The eye consists of conjunctiva, sclera, cornea, lens, retina, iris, pupil, anterior chamber (aqueous humor), canal of Schlemn, posterior chamber (vitreous humor), fovea (focal point), choroids, and optic nerve.

The conjunctiva runs along the inside of the eyelid and the outermost portion of the eye. It meets the sclera, the tough white layer that covers most of the eyeball. Both contain tiny blood vessels that nourish the eye.

Inside the conjunctiva at the center of the eye the cornea lies. This layer of clear tissue with its film of tears provides about two-thirds of the focusing power of the eye. The cornea refracts light as it enters the eye.

The pupil and iris lie behind the cornea. The pupil is the opening through which light passes to the back of the eye. Muscles controlling the iris (the colored part of the eye) allow it to change the size of the pupil to adjust to the amount of light. The pupil becomes larger in dim light and smaller in bright light to protect the delicate retina from excessive light.

Between the cornea and the iris the anterior chamber lies. This space is filled with aqueous humor. This fluid is manufactured in the posterior chamber of the eye. The fluid passes into the anterior chamber through the pupil and then is absorbed into the bloodstream through the canal of Schlemm in the angle where the iris meets the cornea.

Eye

Behind the iris and anterior chamber the lens is. This colorless tissue is enclosed in a capsule and suspended in the middle of the eye by a net of fibers. The lens can change shape in order to focus light rays on the retina.

The bulk of the eyeball, which is behind the lens, is formed by the round posterior chamber. It is filled with a colorless, gelatin-like substance known as the vitreous humor.

Retina is located behind the vitreous chamber. The retina of the eye is equivalent to the film of the camera. Composed of 10 layers, the retina processes the light images projected from the cornea and lens.

The retina is nourished primarily by the choroids. This multilayered tissue, which lies between the retina and the sclera, is composed of veins and arteries.

Fovea located in the center of the retina provides the most acute vision. This section is the most visually sensitive part of the eye.

The optic nerve takes the electrical impulses recorded by the retina and transmits them to the brain. The optic nerve interprets these messages into what we perceive as sight.

EAR

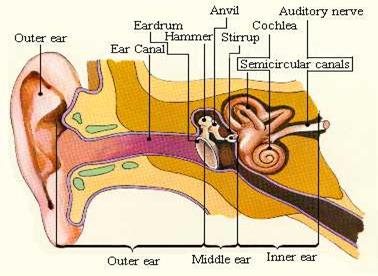

| Ears are the organs of hearing. The ear has three parts: outer ear, middle ear, and inner ear. The auricle (pinna) and outer ear canal, which delivers sound to the middle ear, make up the outer ear, the part we see. Within the outer ear wax-producing glands and hairs that protect the middle ear are located. The function of the middle ear is to deliver sound to the inner ear, where it is processed into a signal that the brain recognizes. The middle ear is a small cavity, with the eardrum on one side and the entrance to the inner ear on the other side. Within the |  Ear

Ear

|

ear there are three small bones (the ossicles) known as the malleus (hammer), incus (anvil), and stapes (stirrup). These bones conduct sound vibrations into the inner ear. The malleus is attached to the lining of the eardrum, the incus is attached to the malleus, and the stapes links the incus to the oval window (the opening to the inner ear).

The middle ear is connected by a narrow channel (the Eustachian tube) to the throat. Ordinarily, the Eustachian tube is closed, but when the person swallows or yawns, it opens to allow an exchange of air, thus equalizing the air pressure within the middle ear and the air pressure outside.

The inner ear contains the most important parts of the hearing mechanism. They are two chambers called the vestibular labyrinth and the cochlea. Tiny hairs line the curves of the cochlea. Both the labyrinth and the cochlea are filled with fluid. When sound waves from the world outside strike the eardrum, it vibrates. These vibrations from the eardrum pass through the bones of the middle ear and into the inner ear through the oval window. Then they disseminate into the cochlea, where they are converted into electrical impulses and are transmitted to the brain by the auditory nerve.

SKIN

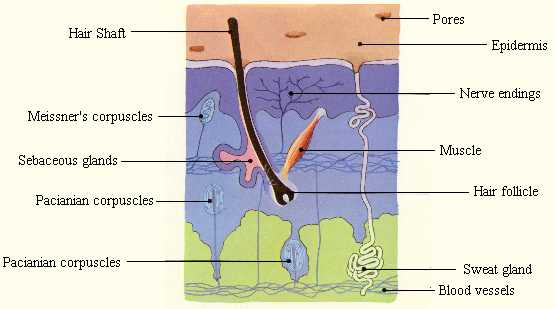

The skin is a unique organ. Approximately the 2 square meters of the skin, that cover the average adult, constitute 15 percent of the body's total weight. Approximately 2.5 square cm of the skin contain millions of cells and many specialized nerve endings for sensing heat, cold, and pain. In addition, each square centimeter contains numerous oil glands, hair follicles, and sweat glands. A complex network of blood vessels nourishes this structure.

The skin protects the internal organs. It serves as heat regulator. Capillaries and blood vessels in the skin dilate or constrict according to the body's temperature. When the person is hot, the sweat on the skin lowers the body's temperature. When the body is chilled, these blood vessels become narrowed, and the skin becomes pale and cold. This constriction decreases the flow of blood through the skin, reducing the heat loss and conserving heat for the main part of the body.

By its texture, temperature, and color the skin gives information about the general health. Sensory nerves send signals to the brain about hazards.

The skin is composed of three layers – the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutaneous tissue.

The epidermis is the top layer of the skin the person sees. The outermost surface of the epidermis is made up of dead skin cells. Squamous cells lie just below the outer surface. Basal cells are at the bottom of the epidermis. The production of new cells, manufactured in the epidermis, takes approximately 1 month, to move upward to the outer surface. As the cells move away from their source of nourishment, they become smaller and flatter, changing into a lifeless protein called keratin. Once on the surface, they remain as a protective cover and then flake off as a result of washing and friction. Thus, the skin is a dynamic organ, constantly being replenished.

The dermis, found beneath the epidermis, makes up 90 percent of the bulk of the skin. It is a dense layer of strong, white fibers (collagen) and yellow, elastic fibers (elastin) in which blood vessels, muscle cells, nerve fibers, lymph channels, hair follicles, and glands are located. The dermis gives strength and elasticity to the skin.

Beneath the dermis the subcutaneous tissue lies. It is composed largely of fat and through which blood vessels and nerves run. This layer, which specializes in manufacturing fat, is unevenly distributed over the body. The roots of oil and sweat glands are located here. Subcutaneous tissue thins and disappears with aging.

Structure of Skin

Дата добавления: 2015-09-11; просмотров: 1518;