Apollo 8 flies around the moon

Apollo 8 was the first spacecraft launched by the larger Saturn V booster. Jim Lovell had joined the astronaut program during Project Gemini and had flown on the Gemini VII and XII missions. Lovell:

On the morning Apollo 8 was launched, December 21, the doubts and the acrimony were at least outwardly forgotten. Borman, Lovell, and Anders were sealed in their spacecraft just after 5:00 am in preparation for a 7:51 launch. By 7:00 the networks’ coverage began and much of the country was awake to witness the event live. Across Europe and in Asia, audiences numbering in the tens of millions also tuned in.

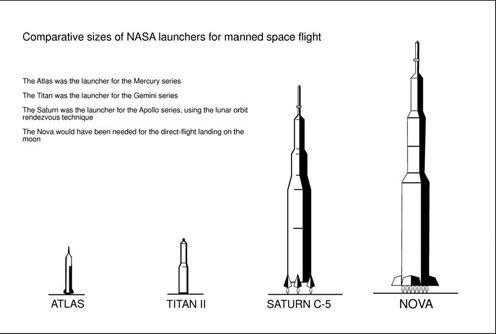

From the moment the Brobdignagian Saturn 5 booster was lit it was clear to TV viewers that this would be like no other launch in history. To the men in the spacecraft – one of whom had never flown in space before and two of whom had ridden only the comparatively puny, 109‑foot Gemini‑Titan – it was clearer still. The Titan had been designed originally as an intercontinental ballistic missile, and if you were unfortunate enough to find yourself strapped in its nose cone – where nothing but a thermonuclear warhead was supposed to be – it felt every bit the ferocious projectile it was. The lightweight rocket fairly leapt off the pad building up velocity and G forces with staggering speed. At the burnout of the second of its two stages, the Titan pulled a crushing eight G’s, causing the average 170 pound astronaut to feel as if he suddenly weighed 1,360 pounds. Just as unsettling as the rocket’s speed and G’s was its orientation. The Titan’s guidance system preferred to do its navigation when the payload and missile were lying on their sides; as the rocket climbed, therefore, it also rolled 90 degrees to the right, causing the horizon outside the astronauts’ windows to change to a vertigo‑inducing vertical. Even more disturbing, the Titan had a huge range of ballistic trajectories programmed into its guidance computer, which aimed the missile below the horizon if it was headed for a military target or above the horizon if it was headed for space. As the rocket rose, the computer would continually hunt for the right orientation, causing the missile to wiggle its nose up and down and left to right, bloodhound‑fashion, for a target that might be Moscow, might be Minsk or might be low Earth orbit, depending upon whether it was carrying warheads or spacemen on that particular mission.

The Saturn 5 was said to be a different beast. Despite the fact that the rocket produced a staggering 7.5 million pounds of thrust – nearly nineteen times more than the Titan – the designers promised that this would be a far smoother booster. Peak gravity loads were said to climb no higher than four G’s, and at some points in the rocket’s powered flight, its gentle acceleration and its unusual trajectory dropped the gravity load slightly below one G. Among the astronauts, many of whom were approaching forty, the Saturn 5 had already earned the sobriquet “the old man’s rocket.” The promised smoothness of the Saturn’s ride, however, was until now just a promise, since no crew had as yet ridden it to space. Within the first minutes of the Apollo 8 mission, Borman, Lovell, and Andres quickly learned that the rumors about the painless rocket were all wonderfully true.

“The first stage was very smooth, and this one is smoother!” Borman exulted midway through the ascent, when the rocket’s giant F‑1 engines had burned out and its smaller J‑2 engines had taken over.

“Roger, smooth and smoother,” Capcom answered.

Less than ten minutes later, the gentle expendable booster completed its useful life, dropping its first two stages in the ocean and placing the astronauts in a stable orbit 102 miles above the Earth.

According to the mission rules for a lunar flight, a ship bound for the moon must spend its first three hours in space circling the Earth in an aptly named “parking orbit.” The crew uses this time to stow equipment, calibrate instruments, take navigational readings, and generally make sure their little ship is fit to leave home. Only when everything checks out are they permitted to relight the Saturn 5’s third stage engine and break the gravitational hold of Earth.

For Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders, it would be a busy three hours, and as soon as the ship was safely in orbit they knew they’d have to get straight to work. Lovell was the first of the trio to unbuckle his seat restraints, and no sooner had he removed the belts and drifted forward than he was struck by a profound feeling of nausea. The astronauts who flew in the early days of the space program had long been warned about the possibility of space sickness in zero G, but in the tiny Mercury and Gemini capsules, where there was barely room to float up from your seat before bonking your head on the hatch, motion‑related queasiness was was not a problem. In Apollo there was more space to move around, and Lovell discovered that this elbow room came at a gastric price.

“Whoa,” Lovell said, as much to himself as in warning to his crewmates. “You don’t want to move too fast.”

He eased his way gently forward, discovering – as centuries of remorseful drinkers with late‑night bed spins had learned – that if he kept his eyes focused on one spot and moved very, very slowly, he could keep his churning innards under control. Easing his way about in this tentative way, Lovell began to negotiate the space directly around his seat, failing to notice that a small metal toggle protruding from the front of his spacesuit had snagged one of the metal struts of the couch. As he moved forward the toggle caught, and a loud pop and hiss echoed through the spacecraft. The astronaut looked down and noticed that his bright yellow life vest, worn as a precaution during liftoffs over water, was ballooning up to full size across his chest.

“Aw, hell,” Lovell muttered, dropping his head into his hand and pushing himself back into his seat.

“What happened?” a startled Anders asked, looking over from the right‑hand couch.

“What does it look like,” Lovell said, more annoyed with himself than his junior pilot. “I think I snagged my vest on something.”

“Well, unsnag it,” Borman said. “We’ve got to get that thing deflated and stowed.”

“I know,” Lovell said, “but how?”

Borman realized Lovell had a point. The emergency life vests were inflated from little canisters of pressurized carbon dioxide that emptied their contents into the bladder of the vest. Since the canisters could not be refilled, deflating the vest required opening its exhaust valve and dumping CO2 into the surrounding air. Out in the ocean this was not a problem, of course, but in a cramped Apollo command module it could be a bit dicey. The cockpit was equipped with cartridges of granular lithium hydroxide that filtered CO2 out of the air, but the cartridges had a saturation point after which they could absorb no more. While there were replacement cartridges on board, it was hardly a good idea to challenge the first cartridge on the first day with a hot belch of carbon dioxide let loose in the small cabin. Borman and Anders looked at Lovell, and the three men shrugged helplessly.

“Apollo 8, Houston. Do you read?” the Capcom called, evidently concerned that he hadn’t heard from the crew for a long minute.

“Roger,” Borman answered. “We had a little incident here. Jim inadvertently popped one life vest, so we’ve got one full Mae West with us.”

“Roger,” the Capcom replied, seemingly without an answer to offer. “Understand.”

With their 180 minutes of Earth orbit ticking away and no time to waste on the trivial matter of a life vest, Lovell and Borman suddenly hit on an answer: the urine dump. In a storage area near the foot of the couches was a long hose connected to a tiny valve leading to the outside of the spacecraft. At the loose end of the hose was a cylindrical assembly. The entire apparatus was known in flying circles as a relief tube. An astronaut in need of the relief the system provided could position the cylinder just so, open the valve to the vacuum outside, and from the comfort of a multi‑million‑dollar spacecraft speeding along at up to 25,000 miles per hour, urinate into the celestial void.

Lovell had availed himself of the relief tube countless times before, but only for its intended purpose. Now he would have to improvise. Strugging out of his life vest, he wrestled it down to the urine port, and with some finessing managed to wedge its nozzle into the tube. It was a forced fit but a workable one. Lovell gave the high sign to Borman, Borman nodded back, and while the commander and the LEM pilot went through their pre‑lunar checklist, Lovell coaxed his life vest back to its deflated state, patiently correcting the first blunder he had committed in nearly 430 hours in space.

Lovell explained Lunar Orbit Insertion (LOI):

The maneuver, known as lunar orbit insertion, or LOI, was a straight‑forward one, but it was fraught with risks. If the engine burned for too short a time, the ship would go into an unpredictable – perhaps uncontrollable – elliptical orbit that would take it high up above the moon when it was over one hemisphere and plunge it down again when it was over the other. If the engine burned too long, the ship would slow too much and drop not just down into lunar orbit but down onto the moon’s surface. Complicating matters, the engine burn would have to take place when the spacecraft was behind the moon, making communication between the ship and the ground impossible. Houston would have to come up with the best burn coordinates it could, feed the data up to the crew, and trust them to carry out the maneuver on their own. The ground controllers knew exactly when the spacecraft should appear from behind the massive lunar shadow if the burn went according to plan, and only if they reacquired Apollo 8’s signal at that time would they know that the LOI had worked as planned.

It was at the 2‑day, 20‑hour, and 4‑minute mark in the flight – when the spacecraft was just a few thousand miles from the moon and more than 200,000 miles from home – that Capcom Jerry Carr radioed the news to the crew that they were cleared to roll the dice and attempt their LOI. On the East Coast it was just before four in the morning on Christmas Eve, in Houston it was nearly three, and in most homes in the Western Hemisphere even the fiercest lunar‑philes were fast asleep.

“Apollo 8, this is Houston,” Carr said. “At 68:04 you are go for LOI.”

“OK,” Borman answered evenly. “Apollo 8 is go.”

“You are riding the best one we can find around,” Carr said, trying to sound encouraging.

“Say again?” Borman said, confused.

“You are riding the best bird we can find,” Carr repeated.

“Roger,” Borman said. “It’s a good one.”

Carr read the engine burn data up to the spacecraft and Lovell, as navigator, tap‑tapped the information into the onboard computer. About half an hour remained before the spacecraft would slip into radio blackout behind the moon, and, as always at times like these, NASA chose to let the minutes pass largely in unmomentous silence. The astronauts, well drilled in the procedures that preceded any engine burn, wordlessly slid into their couches and buckled themselves in place. Of course, if anything went wrong in a Lunar Orbit Insertion, the disaster would go well beyond the poor protection a canvas seat belt could provide. Nevertheless, the mission protocol called for the crew to wear restraints, and restraints were what they would wear.

“Apollo 8, Houston,” Carr signalled up after a long pause.

“We have got our lunar map up and ready to go.”

“Roger,” Borman answered.

“Apollo 8,” Carr said a bit later, “your fuel is holding steady.”

“Roger,” Lovell said.

“Apollo 8, we have you at 9 minutes and 30 seconds till loss of signal.”

“Roger.”

Carr next called up five minutes until loss of signal, then two minutes, then one minute, then, at last, ten seconds. At precisely the instant the flight planners had calculated months before, the spacecraft began to arc behind the moon, and the voices of Capcom and crew began to fracture into crackles in one another’s ears.

“Safe journey, guys,” Carr shouted up, fighting to be heard through the disintegrating communications.

“Thanks a lot, troops,” Anders called back.

“We’ll see you on the other side,” Lovell said.

“You’re go all the way,” Carr said.

And the line went dead.

In the surreal silence, the crew looked at one another. Lovell knew that he should be feeling something, well, profound – but there seemed to be little to feel profound about. Sure, the computers, the Capcom, the hush in his headset all told him that he was moving behind the back of the moon, but to most of his senses, there was nothing to indicate that this monumental event was taking place. He had been weightless moments ago and he was still weightless now; there had been blackness outside his window moments ago and there was blackness now. So the moon was down there somewhere? Well, he’d take it as an article of faith.

Borman turned to his right to consult his crew. “So? Are we go for this thing?”

Lovell and Anders gave their instruments one more practiced perusal.

“We’re go as far as I’m concerned,” Lovell said to Borman.

“Go on this side,” Anders agreed.

From his middle couch, Lovell typed the last instructions into the computer. About five seconds before the scheduled firing time a display screen flashed a small, blinking “99:40.” This cryptic number was one of the spacecraft’s final hedges against pilot error. It was the computer’s “are you sure?” code, its “last chance” code, its “make‑certain‑you‑know‑what‑you’re‑doing‑because‑you’re‑about‑to‑go‑for‑a‑hell‑of‑a‑ride” code. Beneath the flashing numbers was a small button marked “Proceed.” Lovell stared at the 99:40, then at the Proceed button, then back at the 99:40, then back at the Proceed. Then, just before the five seconds had melted away, he covered the button with his index finger and pressed.

For an instant the astronauts noticed nothing; then all at once they felt and heard a rumble at their backs. A few feet behind them, in giant tanks tucked into the rear of the spacecraft, valves opened and fluid began flowing, and from two nozzles two different fuel ingredients swirled together in a combustion chamber. The ingredients – a hydrazine, dimethylhydrazine mixture, and nitrogen tetroxide – were known as hypergolics, and what made hypergolics special was their tendency to detonate in each other’s presence. Unlike gasoline or diesel fuel or liquid hydrogen, all of which need a spark to release the energy stored in their molecular bonds, hypergolics get their kick from the catalytically contentious relationship they have with one another. Stir two hypergolics together and they will begin tangling chemically, like game‑cocks in a cage; keep them together long enough, and confine their interaction well enough, and they will start releasing prodigious amounts of energy.

At Lovell’s, Anders’s, and Borman’s backs, such an explosive interplay was now taking place. As the chemicals flashed to life inside the combustion chamber, a searing exhaust flew from the engine bell at the rear of the ship; ever so subtly the spacecraft began to slow. Borman, Lovell and Anders felt themselves being pressed backward in their couches. The zero g that had become so comfortable was now a fraction of one G, and the astronauts’ body weight rose from nothing to a handful of pounds. Lovell looked at Borman and flashed a thumbs up; Borman smiled tightly. For four and a half minutes the engine burned, then the fire in its innards shut down.

Lovell glanced at his instrument panel. His eyes sought the readout that was labeled “Delta V.” The “V” stood for velocity, “Delta” meant change, and together they would reveal how much the speed of the ship had slowed as a result of the chemical brake the hypergolics had applied. Lovell found the number and wanted to pump a fist in the air – 2,800! Perfect! 2,800 feet per second was something less than a screeching halt when you were zipping along at 7,500, but it was exactly the amount you’d need to subtract if you wanted to quit your circumlunar trajectory and surrender yourself to the gravity of the moon.

Next to the Delta V was another readout, one that only moments before had been blank. Now it displayed two numbers, 60.5 and 169.1. These were pericynthion and apocynthion readings – or closest and farthest approaches to the moon. Any old body whizzing past the moon could get a pericynthion number, but the only way you could get pericynthion and apocynthion was when you weren’t just flying by but actually circling the lunar globe. Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders, the numbers indicated, were now lunar satellites, orbiting the moon in an egg‑shaped trajectory that took them 169.1 miles high by 60.5 miles low.

“We did it!” Lovell was exultant.

“Right down the pike,” Anders said.

“Orbit attained,” Borman agreed. “Now let’s hope it fires tomorrow to take us home again.” Achieving orbit around the moon, like disappearing behind it minutes earlier, was a bit of an academic experience for the astronauts. Once the engine had quit firing and the crew had become weightless again, there was nothing beyond the data on their dashboard to confirm what they had achieved. The moon was just five dozen miles below them, but the spacecraft’s upward‑facing windows had not permitted the astronauts a look. Borman, Lovell, and Anders were three men who had backed into a picture gallery and had not yet turned around to see what was inside. Now, however, they had the luxury – and, with reaquisition of ground contact still twenty‑five minutes away, the undisturbed privacy – to conduct their first survey of the body whose gravity was holding them fast.

Borman grabbed the attitude control handle to the right of his seat and vented a breath of propellant from the thrusters arrayed around the outside of the spacecraft. The ship glided into motion, rolling slowly counter clockwise. The first 90 degrees of the roll tipped the weightless astronauts onto their sides, with Borman at the bottom, Lovell in the middle, and Anders at the top of the stack; the next 90 moved them upside down, so the moon that had been below them was all at once above. It was into Borman’s left‑hand window that the pale gray, plastery surface of the land below first rolled, and so it was Borman whose eyes widened first. Lovell’s center window was filled next, and finally Anders’s. The two crewmen responded with the same gape the commander had.

“Magnificent,” someone whispered. It might have been Borman; it might have been Lovell; it might have been Anders.

“Stupendous,” someone answered.

Gliding beneath them was a ravaged, fractured, tortured panorama that had been previously glimpsed by robot probes but never before by the human eye. Ranging out in all directions was an endless, lovely‑ugly expanse of hundreds – no, thousands; no, tens of thousands – of craters, pits, and gouges that dated back hundreds – no, thousands; no, millions – of millennia. There were craters next to craters, craters overlapping craters, craters obliterating craters. There were craters the size of football fields, craters the size of large islands, craters the size of small nations.

Many of the ancient pits had been catalogued and named by astronomers who first analyzed the pictures sent back from probes, and after months of study these had become as familiar to the astronauts as earthly landmarks. There were the craters Daedalus and Icarus, Korolev and Gagarin, Pasteur and Einstein and Tsiolkovsky. Scattered about the terrain were also dozens of other craters that had never been seen by human or robot. The spellbound astronauts did what they could to take this all in, pressing their faces against their five tiny windows and, for the moment at least, forgetting altogether the flight plan or the mission or the hundreds of people in Houston waiting to hear their voices.

From over the advancing horizon, something wispy started to appear. It was subtly white and subtly blue and subtly brown, and it seemed to be cliimbing straght up from the drab terrain. The three astronauts knew at once what they were seeing, but Borman identified it anyway.

“Earthrise,” the commander said quietly.

“Get the cameras,” Lovell said quickly to Anders.

“Are you sure?” asked Anders, the mission’s photographer and cartographer. “Shouldn’t we wait for scheduled photography times?”

Lovell gazed at the shimmery planet floating up over the scarred, pocked moon; then looked at his junior crewmate.

“Get the cameras,” he repeated.

On Christmas Day Lovell had arranged to have a gift delivered to his wife while Apollo 8 was in lunar orbit. The gift card read “Merry Christmas from the Man in the Moon”.

The crew had broadcast from lunar orbit on Christmas Eve. Lovell:

“What you’re seeing,” said Anders as he steadied the camera and braced his buoyant body against the bulkhead of the ship, “is a view of the Earth above the lunar horizon. We’re going to follow along for a while and then turn around and give you a view of the long, shadowed terrain.”

“We’ve been orbiting at sixty miles for the last sixteen hours,” Borman said while Anders pointed the lens downward at the surface, “conducting experiments, taking pictures, and firing our spacecraft engine to maneuver around. And over the hours, the moon has become a different thing for each one of us. My own impression is that it is a vast lonely, forbidding expanse of nothing that looks rather like clouds and clouds of pumice stone. It certainly would not be a very inviting place to live or work.”

“Frank, my thoughts are similar,” Lovell said. “The loneliness up here is awe inspiring. It makes you realize just what you have back on Earth. The Earth from here is an oasis in the vastness of space.”

“The thing that impressed me the most,” Anders took over, “was the lunar sunrises and sunsets. The sky is pitch black, the moon is quite light, and the contrast between the two is a vivid line.”

“Actually,” Lovell added, “the best way to describe the whole area is an expanse of black and white. Absolutely no color.”

The flight plan called for the broadcast to last twenty‑four minutes, during which time the ship would glide across the lunar equator from east to west, covering about 72 degrees of its 36 degree orbit. The astronauts were to take this time to explain and describe, point and instruct, and try to convey through words and grainy pictures what they were seeing.

On Christmas Eve they finished their broadcast by filming through the window and reading from a prepared script. Anders said:

“‘We are now approaching the lunar sunrise, and for all the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message we would like to send to you.

“In the beginning,” he began, “God created the Heaven and the Earth. And the Earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.” Anders read slowly for four lines, then passed the paper on to Lovell.

“And God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.” Lovell read four lines of his own and handed the paper to Borman.

“And God said, let the waters under the Heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear.” Borman continued until he reached the end of the passage, concluding with, “And God saw that it was good.”

When the final line was done, Borman put down the paper. “And from the crew of Apollo 8,” his voice crackled down through 239,000 miles of space, “we close with good night, good luck, a merry Christmas, and God bless all of you on the good Earth.”

After the broadcast it was time for the Trans Earth Injection burn. Lovell:

Just as Jerry Carr had done for the LOI burn, Mattingly read up the data and coordinates for the Trans Earth Injection, or TEI, burn. Once again, Lovell typed the figures into his computer, the astronauts strapped themselves into their couches, and Houston fidgeted in silence as the minutes ticked away to loss of signal. Unlike the LOI burn, the TEI burn would require the ship to be pointed forward, adding feet per second to its speed rather than subtracting them. Also unlike the LOI burn, during TEI there would be no free‑return slingshot to send the ship home in the event that the engine failed to light. If the hydrazine, dimethylhydrazine, and nitrogen tetroxide did not mix and burn and discharge just so, Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders would become permanent satellites of Earth’s lunar satellite, expiring from suffocation in about a week and then continuing to circle the moon, once every two hours, for hundreds – no, thousands; no, millions – of years.

The crew slipped into radio silence, and the controllers sat quietly and waited. Somewhere behind the lunar mass, the giant service propulsion engine either was or wasn’t firing, and Houston wouldn’t know one way or the other for forty minutes. Mission Control sat in silence for this two thirds of an hour, and as the last seconds ticked away, Ken Mattingly began trying to raise the ship. “Apollo 8, Houston,” he said. There was no response.

Eight seconds later: “Apollo 8, Houston.” No response. Forty‑eight seconds later: “Apollo 8, Houston.”

Forty‑eight seconds later: “Apollo 8, Houston.”

For one hundred more seconds the controllers sat in silence, and then, all at once: “Houston, Apollo 8,” they heard Lovell call exultantly into their headsets, his tone alone confirming that the engine had burned as intended. “Please be informed, there is a Santa Claus.”

“That’s affirmative,” Mattingly called back, audibly relieved. “You are the best ones to know.”

The spacecraft splashed down in the Pacific at 10:51 a.m. Houston time on December 27. It was before dawn in the prime recovery zone, about one thousand miles southwest of Hawaii, and the crew had to wait ninety minutes in the hot, bobbing craft before the sun rose and the rescue team could pick them up. The command module hit the water and then rotated upside down, into what NASA called the stable 2 position (stable 1 was right side up). Borman pressed a button inflating balloons at the top of the spacecraft cone, and the ship slowly righted itself. From the time the crew climbed out and stepped before the television cameras, it was clear that the national ovation that would greet them would surprise even publicity‑savvy NASA. Borman, Lovell, and Anders became overnight heroes, receiving award after award at one testimonial dinner after another. They became Time magazine’s Men of the Year, addressed a joint session of Congress, rode in a New York City ticker‑tape parade, met outgoing President Lyndon Johnson, met incoming President Richard Nixon.

The honors were deserved, but in a surprisingly fleeting couple of weeks, they ended. When the crew of Apollo 8 returned, the nation had satisfied itself that it could get to the moon; the passion now was to get on the moon. In the wake of the mission’s triumph, the Agency decided that it would need just two more warm‑up flights to prove the soundness of its equipment and its flight plan. Then sometime in July, Apollo 11 – the lucky Apollo 11 – would be sent out to make the descent into the ancient lunar dust.

Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin would make the trip, and at the moment it looked like it would be Armstrong who would take the historic first step.

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-05-13; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 1050;