The Apollo program is revised

After the Apollo 1 disaster, the next five Apollo missions were unmanned tests. Apollo 7 was manned by Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham. Frank Borman was the astronaut on the NASA commission which investigated the Apollo 1 disaster, as a result of which the Apollo spacecraft was improved. In his biographical accounts, Jim Lovell referred to himself in the third person. Jim Lovell:

With Borman as point man and the rest of the pilots now backing him up more quietly, the astronauts got nearly everything they had been lobbying for in a new, safer spacecraft. They had wanted a gas‑operated hatch that could be opened in seven seconds, and they got it; they had wanted upgraded, fireproof wiring throughout the ship, and they got it; they had wanted non‑flammable Beta cloth in the spacesuits and all fabric surfaces, and they got it. Most important, they had wanted the firefeeding, 100 percent oxygen atmosphere that swirled through the ship when it was on the pad to be replaced by a far less dangerous 60–40 oxgen‑nitrogen mix. Not surprisingly, they got that too.

The Apollo program itself was revised. Jim Lovell:

The modifications being made to the Apollo spacecraft were not the only changes NASA explored in the wake of the fire. Also scrutinized were the missions those ships would be sent on. Though John Kennedy had been dead since 1963, his grand promise – or damned promise, depending on how you looked at it – to have America on the moon before 1970 still loomed over the Agency. NASA officials would have considered it a profound failure not to meet that bold challenge, but they would have considered it an even greater failure to lose another crew in the effort. Accordingly, chastened Agency brass began making it clear, publicly and privately, that while America was still aiming for the moon before the end of the decade, the breathless gallop of the past few years would now be replaced by a nice, safe lope.

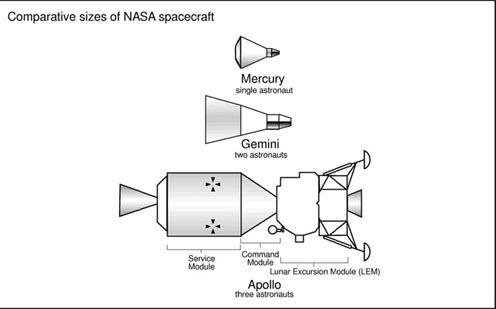

According to the tentative flight schedule, the first manned Apollo flight would be Schirra’s Apollo 7, intended to be nothing more than a shakedown cruise of the still‑suspect command module in low Earth orbit. Next would come Apollo 8, during which Jim McDivitt, Dave Scott, and Rusty Schweickart would go back into near‑Earth space to test‑drive both the command module and the lunar excursion module, or LEM, the ugly, buggy, leggy lander that would carry astronauts down to the surface of the moon. Next, Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders would pilot Apollo 9 on a similar two‑craft mission, this time taking the ships to a vertiginous altitude of 4,000 miles, in order to practice the hair‑raising, high‑speed re‑entry techniques that would be necessary for a safe return from the moon.

After that, things were wide open. The program was scheduled to continue through Apollo 20, and, in theory any mission from Apollo 10 on could be the first to set two men down on the moon’s surface. But which mission and which two men were utterly unsettled. NASA was determined not to rush things, and if it took until well into the Apollo teens before all the equipment checked out and a landing looked reasonably safe, then it would have to take that long.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-13; просмотров: 925;