Bigger (and Cleaner) Bangs for the Buck: Smokeless Powder and High Explosives

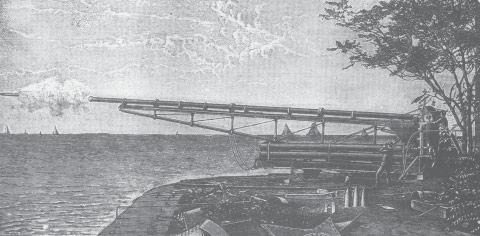

Eight‑inch dynamite gun being tested. This weapon’s military service was short because it was so dangerous to use. Dynamite is too sensitive to be a shell filling.

President Theodore Roosevelt is famous for advising his countrymen to “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” But prior to this day, July 1, 1898, he and his fellow war hawks had been roaring at the top of their voices while carrying a toothpick – at least as far as land forces went. The navy was moderately large and more than moderately modern. The army, though, had only 28,183 men, and many of them were needed on the still‑not‑quite‑settled western frontier.

Consequently, at least half of the troops here in Cuba were volunteers, not regulars. And that requires a brief explanation of just what “volunteer” means.

Volunteer units were an outgrowth of the country’s ancient militia system, which has its roots in the Dark Ages. Militia were originally all men able to bear arms. They could be called upon by the monarch to fight in his wars. Later, there were limitations on who could be called up and for how long and where.

Age limits were set. In the United States today, all males are between the ages of 17 and 45 are the militia. In England, in the Middle Ages, militia were required to serve for only 40 days, and they had to be paid by the royal treasury for any duty outside their own counties. In colonial America, militia could not be required to serve outside their own colonies. For troops to be used outside the colonies, colonial authorities relied on “volunteers.” These were men who formed their own military units, elected their own officers, provided their own weapons, and served under regular army officers for a limited time or for the duration of the war. Until the 20th century, the United States depended heavily on volunteer units in its wars.

Originally, the volunteers provided their own weapons, but, by the end of the 19th century, the states provided many units with their arms. The Krag Jorgensen repeating rifle and carbine had just been adopted for the regular army.

Krags were not for sale to private owners, however, and none of the states were ready to invest large sums in new rifles for militia units – many of which were not even in existence. Consequently, most of the troops closing in on Santiago de Cuba had single‑shot rifles using the old standard cartridge, the .45–70, adopted in 1873. Single‑shot rifles could not, of course, fire as fast as repeaters. But the big disadvantage of these single‑shots, most of them varieties of the Springfield “trap door” action rifle, was that they used black powder, not smokeless. We’ll see in a moment what that meant. Only one unit of volunteers, the Rough Riders, composed of cowboys and Ivy Leaguers recruited by Theodore Roosevelt, had Krags. Political connections are a wonderful thing.

The Spanish regulars had the Model 1893 or 1895 Mauser, 7 mm bolt action repeaters. Mauser’s late model rifles were by far the best military rifles of the day. The Spanish also had Krupp quick‑firing field pieces. (See Chapter 28.) Of the U.S. troops, neither regulars nor reserves had modern artillery.

What the Americans had, at least in the field, were numbers. The right wing of the American army, under Brigadier General Henry L. Lawton, had 6,653 men and four field pieces. It was moving against the Spanish fortifications around the village of El Caney, where Spanish General Joaquin Vara de Ray had 520 men. Lawton’s troops were to take El Caney and swing around the main defenses of Santiago de Cuba. At the same time, the main body was to attack the Spanish line on the crest of the San Juan Heights. The dismounted cavalry division, which included Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, the 9th and 10th regiments of African American cavalry (“Buffalo Soldiers”) and the 1st, 3rd, and 6th cavalry regiments, formed the right wing of the main body. It faced fortifications on what became known as Kettle Hill – not San Juan Hill, which was a short distance to the south. The Rough Riders were the only volunteers in the force, and like the rest of the division, who were regulars, they had modern rifles.

The day before, Lawton had surveyed his objective and estimated that his men would take it in two hours. Planning for the main assault was based on that estimate. Given the odds Lawton enjoyed, that was a most reasonable estimate.

To understand what kind of advantage 10‑to‑one odds gives a military unit, let’s consider some extremely simplistic propositions. Say one side has 100 men and the other side 1,000, and say that, on each exchange of fire, 10 percent of each side score hits. On the first exchange the larger force will be reduced to 990 men, but the second will be annihilated. Say only 5 percent score hits on each exchange. On the first exchange, the larger force will be left with 995 soldiers; the smaller one with 50. Of course, real life is more complicated than that (at least now). In the days when soldiers stood shoulder to shoulder and fired volleys at each other, that proposition would have been more accurate.

But if the defenders are entrenched, as the Spanish were, they are harder to hit, especially if both sides are relying almost exclusively on rifles, as both sides were. When they are hit, though, the wound is likely to be fatal, because it would usually be in the head. Attackers were harder to hit, too. American troops had learned in the Civil War to advance by rushes, dropping down behind shelter and firing to cover other soldiers’ advances. Attackers, when hit, are less likely to be hit fatally, because hits would not be confined to the head. All their rifles – repeaters and single‑shots – were breech‑loaders, so a soldier need not expose himself to reload.

Even with all these qualifications, though, 10‑to‑one odds gave the larger group a tremendous advantage. As the previous propositions show, the longer the fight goes on, the more heavily the weaker side is outnumbered. An old rule of thumb is that an attacker should have a 3‑to‑one numerical advantage over the defender. Lawton had better than 10‑to‑one.

Artillery support for the American attackers was virtually nonexistent.

Lawton’s artillery fired about one round every five minutes, and they fired from long range without much accuracy. It may be that they were trying to avoid the troubles being suffered by the main force artillery. Those four guns were emplaced on a hilltop, because the Americans had no guns capable of indirect fire. Each time a gun fired, it generated an enormous cloud of thick white smoke that made it impossible to see the target. It also made the guns obvious to the Spanish, who had two Krupp quick‑firing pieces using smokeless powder. The Americans couldn’t locate the Spanish guns if the air were clear. It wasn’t clear. Their gunners were blinded by their own smoke. Finally, they were driven off the hill.

Back at El Caney, the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, a volunteer outfit, advanced and opened fire on the Spaniards. The Spanish soldiers were hidden in trenches, fox holes, wooden block houses, and a stone fort, so the Yankee volunteers could only fire at the general area. The Spanish, though, knew that behind each puff of smoke was an enemy rifleman. Their return fire was so heavy the volunteers were forced back. The regulars in the division, including the 24th and 25th Regiments, “Buffalo Soldier” (African‑American) infantry, had smokeless powder, but there were so many volunteers among them that the Spanish soldiers could easily see where to concentrate their fire.

Troops in the main body were told to march up to the San Juan River and wait for further orders. The “further orders” were presumably to advance when Lawton had taken El Caney and moved south. They waited, some standing in the river. The trouble was compounded when an American observation balloon, which had been observing the area from a half‑mile behind the front line, was moved to the front line and then its anchor ropes became entangled in the treetops. Stuck 50 feet above the front line, the balloon showed the Spanish exactly where the American troops were, even though they were hidden in the jungle. The Spanish fired into that area.

Eventually, doing nothing but taking casualties got to be too much for the Americans. They moved up the hills. Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders got the credit for taking Kettle Hill, but the black “Buffalo Soldiers” of the 9th Cavalry got to the summit first. San Juan Hill proved to be a tougher proposition. The turning point was provided by a maverick second lieutenant. John H. Parker, six years out of West Point, was considered a machine gun fanatic by his comrades. When he saw that the expedition to Cuba was leaving behind four Gatling guns, he begged his commanding officer to take them. He was refused. Although Gatling guns had been used effectively in the Civil War, the army still didn’t believe in machine guns. Parker went through channels until he found a general who let him form a machine gun battery and take the Gatlings with him.

With the American troops pinned down on the slopes of San Juan Hill, Parker’s mule‑drawn Gatling guns galloped up and his troops unlimbered them.

The four guns opened fire, each squirting out bullets at the rate of 900 rounds a minute. Fortunately, Parker’s guns used the.30 smokeless Krag cartridges. His men could see what they were shooting at. The American troops saw the dust kicked up by the spray of bullets as they swept across the Spanish trenches. The Spanish began to withdraw. By this time, many of the American officers had been killed or wounded, but their troops spontaneously charged up the hill and took the fort at its summit.

El Caney had still not been taken. The hill that was to have been taken in two hours held out for 10. Finally, the Spanish troops began to run out of ammunition. The Spanish commanding general, Arsenio Linares, kept the bulk of his army in Santiago and sent Vara de Ray neither men nor more ammunition.

The American stormed the fort. They took 120 prisoners. Of the 520 men in the garrison, 215, including General Vara de Ray, had been killed and some 300 wounded. American casualties came to 205 killed and almost 1,200 wounded.

Both the Spanish and Americans at El Caney were brave soldiers. And both had been let down by their leaders – the Spanish by their commander’s refusal to reinforce or even resupply them; the Americans by their leaders’ failure to amend the order to wait at the San Juan River, by their neglect of what proved to be the decisive weapon – the Gatling gun – and by the government’s failure to obtain smokeless powder.

Smokeless powder had been invented in 1885 by Paul Vieille, a French chemist, and the French put it into service almost immediately, bringing out a new 8

mm rifle to use the new powder in 1886. That was 12 years before the Spanish‑American War. The development of smokeless powder was part of a chemical revolution that began in the mid‑19th century and included, among other things, dyes from coal tar, anaesthetics, aspirin, heroin, and dynamite.

Dynamite, patented in 1866, was made in many varieties, some, such as gelatine dynamite, extremely powerful, all extremely sensitive. Dynamite is based on an early explosive, nitroglycerin, which is too sensitive for almost any use.

Alfred Nobel first mixed nitroglycerin with an absorbent earth to desensitize it.

He later mixed it with other explosives, such as ammonium nitrate, potassium chlorate, or nitro cotton to obtain a very powerful explosive that was still safe to handle (with care). Gun‑makers tried to use dynamite for a shell filling (Chapter 19) but it proved to be too dangerous. It could never be used as a propellant.

It is what is called a high explosive: one that almost instantly decomposes into a huge amount of gas, whether it is confined or unconfined. This reaction is called detonation. Propellants, like black powder or smokeless powder, decompose more slowly. They are said to burn, although smokeless powder, if confined tightly enough, may also detonate.

Nitroglycerin is a compound of nitric acid and glycerin. About the time Nobel was experimenting with nitroglycerin, other chemists were nitrating other organic substances. Nitrating cotton a little produced nitro cotton, a component of gelatine dynamite. Nitrating it a lot produced guncotton, a rather sensitive explosive once used as a filling for torpedoes, but now an ingredient of smokeless powder.

TNT, or trinitrotoluene, became extremely popular as a filling for shells, torpedoes, aerial bombs, and hand grenades because it combines great power with a reasonable lack of sensitivity. It was widely used in both world wars.

Many new high explosives have been developed since the war. They are never used as propellants – the many varieties of smokeless powder handle that chore – but they have completely replaced “low explosives,” such as black powder as fillings for shells and bombs. When a black powder shell exploded, it burst into a few large pieces, none with enough velocity to carry far. High explosives shatter a shell into thousands of tiny, sharp metal fragments traveling at high velocity. These fragments are so effective against personnel that they have completely replaced shrapnel. Against solid objects – forts, tanks, ships, and so on – high explosives are infinitely more effective than black powder. And they make possible the shaped charge.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1313;