Bombs Bursting in Air”: Explosive Shells

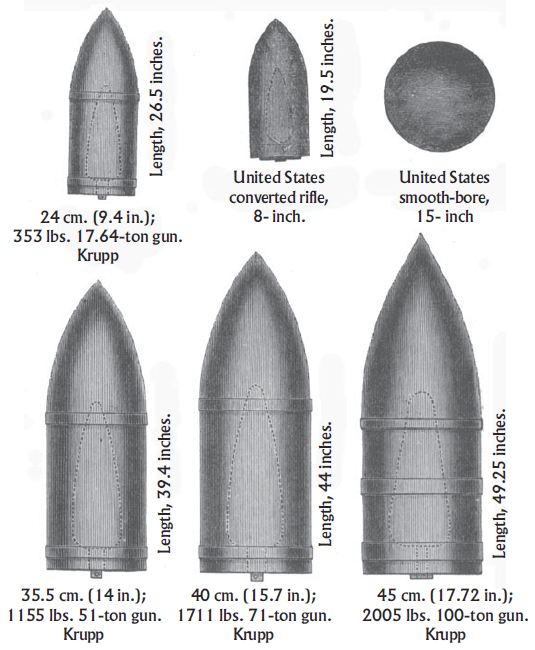

One cannonball and a variety of explosive shells.

When Francis Scott Key located the flag by “the rockets’ red glare and the bombs bursting in air,” he was watching the effects of two weapons which had been developing for centuries and would turn into devices no one in the early 19th century could have imagined. Of the two – the rocket and the artillery shell – the rocket was far older. The Chinese had been using rockets in war before anybody had guns. And as we know, rockets would not only put men on the moon, they would develop into intercontinental engines of destruction.

The artillery shell, in contrast, was not quite three centuries old. The first recorded use was by the Turks at the siege of Rhodes in 1522. The Turkish bombards hurled huge shells over the walls of the fortress. The shells made a tremendous flash and noise when they exploded, but they weren’t much good for knocking down walls. They could knock down flimsy houses and they could kill by concussion anyone unlucky enough to be near them when they went off. But mostly, they were useful only to terrify the defenders. In the case of Rhodes, though, the defenders were the Order of the Knights of the Hospital of St. John the Baptist of Jerusalem (the Crusading Knight Hospitalers), a military unit that was among the least susceptible to terror in all history. The Turks eventually took Rhodes after expending rivers of blood, but the explosive shells weren’t much help. There was no indication in those days that the explosive shell would some‑day be the most deadly device in land warfare and the supreme weapon at sea.

The explosive shell developed from the hand grenade. The first shells were hollow metal spheres filled with gunpowder. There was a hole in the ball, and it was covered with a fireproof sack filled with a flammable compound. A hole in the sack, on the other side of the sphere, faced the gun’s powder charge. When the gun went off, it ignited the compound in the sack, which burned around to the hole in the shell, and the shell exploded. Later, artillerymen used wooden or metal tubes filled with a priming compound. They hammered these into the hole in the shell. At first, they loaded the shell with the tube facing the gun’s powder charge. Too often, though, the propelling charge did not merely ignite the shell’s fuse. It drove the fuse into the shell, which then went off inside the gun, destroying the gun and gunners.

That led to double‑firing – the gunner placed the shell in the gun with fuse facing the muzzle. He then lit the fuse and, immediately after, applied fire to the gun’s touch‑hole. This could only be done with short‑barreled guns. There was no way a gunner could reach deep into a cannon’s bore to ignite the shell.

The early bombards had short barrels for the size of their shells. Later shell‑firing guns were the mortar, a very short barreled gun that shot shells only at a high trajectory, and the howitzer, a gun with a slightly longer barrel that could fire shells at a higher velocity and on a flatter trajectory. With any gun, double‑firing called for good reflexes and may be one of the reasons artillerymen, unlike most soldiers, were reputed to abstain from drunkenness, lechery, and the use of naughty words. If the gun misfired, the gunner would be standing right next to a bomb that would explode an instant later. Finally, someone discovered that the flash of the propelling charge would ignite the shell’s fuse even if the fuse was facing the muzzle.

Early shells, then, were pretty dangerous gadgets to use. They were not much more dangerous, though, to the enemy. Because shells were hollow, they were useless for battering walls. The shell would either flatten or shatter on striking a stone wall, and an unconfined explosion would have little effect. Used against personnel, a shell would break up into a few large pieces. Gunpowder did not have the shattering effect of high explosive, so the carnage caused by shell fragments was unknown until the very late 19th or early 20th centuries.

That’s another reason first shells were used in mortars: those short‑barreled cannons were used to threw their projectiles at a high angle to clear the walls of forts. The timing of shell bursts was none too precise in those early days. Shells frequently did not explode for some time after landing. At other times, they exploded before reaching the target – Keys’s “bombs bursting in air.”

A British artillery officer, Lieutenant Henry Shrapnel, saw a way to improve the shell’s performance against personnel. He invented a shell that was much like the early hand grenades – an iron ball filled with lead bullets and enough gunpowder to burst it open.

Before the shrapnel shell, artillerymen had only three missiles to use against infantry. For long range use against infantry, they used cannonballs – “solid shot,” in gunners’ lingo. They fired directly at the lines of marching men. The shot skipped along the ground, ricocheting at flat angles and destroying whatever it hit. Against masses of infantry, like the Swiss or Spanish phalanxes, cannonballs were deadly, indeed. Fired against the flanks of the later “thin line”

formation, they could also kill a number of men with one shot. That, however, took either extremely good marksmanship or a great deal of luck. Infantry could often evade destruction all together by falling flat, so the cannonballs flew over them. When the infantry got close, the artillery became extremely deadly. Grape shot – a number of iron or lead balls packed in a wood‑reinforced canvass bag –, spread out like shot from a giant shotgun and took out bunches of infantrymen or cavalrymen before they got to musket range. When the attackers came closer, the gunners switched to case or cannister shot – smaller and more numerous balls packed in tin cans, which was even more deadly. Shrapnel’s invention made it possible to produce the effects of grape or cannister shot at ranges impossible with small shot fired directly from the cannons Shrapnel shells ac‑celerated the development of howitzer, shell guns that could fire directly at infantry. The knowledge that a cannon’s muzzle blast would ignite a fuse even when facing away from the powder charge made shrapnel a popular choice for use against infantry or cavalry.

When rifled artillery capable of firing elongated projectiles was introduced, shrapnel shells were adapted to the new guns. These new shrapnel shells have been called “guns fired by guns.” The bursting charge of gunpowder was in the rear of the shell. When ignited by the time fuse, it shot the load of lead balls out of the front of the shell. The shell was a kind of flying shotgun. Shrapnel was used extensively in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was the reason all armies adopted the steel helmet in World War I. Experience in that war, however, showed that shrapnel was no more effective against personnel than ordinary high explosive shells. High explosives shattered shells into thousands of jagged fragments, which killed exposed enemy soldiers quite efficiently, and high explosive could also destroy fortifications, something shrapnel could not do. Although the term is common today, shrapnel has not been used since the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939. When newspaper accounts mention “shrapnel” they mean shell or bomb fragments.

High explosives have been around since the late 19th century, but at first they were far too sensitive to use as filling for shells. Around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, a peculiar weapon called a “dynamite gun” appeared.

It had a long barrel and fired a comparatively small‑caliber brass shell filled with dynamite. It did not use a normal propelling charge: The shock of the explosion might well detonate the shell before it left the gun. Instead, a small charge of black powder was fired in a tube beneath the gun barrel. This forced gas through a hole the barrel, giving the dynamite shell a gentle shove. The dynamite gun was used to some extent in the Cuban rebellion and the Spanish‑American War that followed. When the shell landed, the blast was most impressive, but the thin‑walled shell did not provide much fragmentation, and it exploded as soon as it hit anything more solid than air, which prevented penetration. And it was so dangerous, the gunners who used it were terrified of their weapon. As a result of these problems, the dynamite gun’s career was short, and dynamite has not been used as a shell filling since. Artilleryists switched to more stable explosives like picric acid and TNT.

Shells and cannons have developed steadily. In World War II, a new, high tech fuse was developed to replace the ancient timed fuse based on a burning train of gunpowder and the more modern clockwork fuse. Timing was never precise with the gunpowder fuse, and even the clockwork type left much to be desired. The new “proximity fuse” used a miniature radar to explode the shell when it was a fixed distance from the target. No longer would air bursts be too high to be effective or delayed so long the shell buried itself in the ground before exploding. The new fuse made artillery an even more potent antiaircraft and anti‑personnel weapon. In World War II about two thirds of the casualties among soldiers were caused by artillery.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 2889;