The Secret Ingredient

When I was a teenager, my mother began listening to French instructional programs in order to brush up. She was proud of me when I began sitting and listening with her. “Perhaps my son isn’t a square physics kid after all,” she thought. And, in fact, I found the experience utterly enthralling. After many months, however, my mother’s pride turned to worry, because whenever she attempted to banter in even the most elementary French with me, I would stare back, dumbfounded. “Why isn’t this kid learning French?” she fretted.

What I didn’t tell my mother was that I wasn’t trying to learn French. Why was I bothering to listen to a program I could not comprehend? I will let you in on my secret in a moment, but in the meantime I can tell you what I was not listening to it for: the speech sounds. No one would set aside a half hour each day for months in order to listen to unintelligible speech. Foreign speech sounds can pique our curiosity, but we don’t go out of our way to hear them. If people loved foreign speech sounds, there would be a market for them; we would set our alarm clocks to blare German at 5:30 a.m., listen to Navajo on the way to work in the car, and put on Bushmen clicks as background for our dinner parties. No. I was not listening to the French program for the speech sounds. Speech doesn’t enthrall us–not even in French.

Whereas foreign speech sounds don’t make it as a form of entertainment, music is quintessentially entertaining. Music does get piped into our alarm clocks, car radios, and dinner parties. Music has its own vibrant industry, whereas no one is foolish enough to see a business opportunity in easy‑listening foreign speech sounds. And this motivates the following question. Why is music so evocative? Why doesn’t music feel like listening to speech sounds, or animal calls, or garbage disposal rumbles? Put simply: why is music nice to listen to?

In an effort to answer, let’s go back to the French instructional program and my proud, and then concerned, mother. Why was I joining my mom each day for a lesson I couldn’t comprehend, and had no intention of comprehending? Truth be told, it wasn’t an audiotape we were listening to, but a television show. And it wasn’t the meaningless‑to‑me speech sounds that lured me in, but one of the actors. A young French actress, in particular. Her hair, her smile, her mannerisms, her pout . . . but I digress. I wasn’t watching for the French language so much as for the French people, one in particular. Sorry, Mom!

What was evocative about the show and kept me wanting more was the human element. The most important thing in the lives of our ancestors was the other people around them, and it is on the faces and bodies of other people that we find the most emotionally evocative stimuli. So when one finds a human artifact that is capable of evoking strong feelings, my hunch is that it looks or sounds human in some way. This is, I suggest, an important clue to the nature of music.

Let’s take a step back from speech and music, and look for a moment at evocative and nonevocative visual stimuli in order to see whether evocativeness springs from people. In particular, consider two kinds of visual stimuli, writing and color–each an area of my research covered in my previous book, The Vision Revolution .

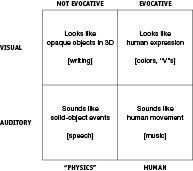

Writing, I have argued, has culturally evolved over centuries to look like natural objects, and to have the contour structures found in three‑dimensional scenes of opaque objects. The nature that underlies writing is, then, “opaque objects in 3‑D,” and that is not a specifically human thing. Writing looks like objects, not humans, and thus only has the evocative power expected of opaque objects: little or none. That’s why most writing–like the letters and words on this page–is not emotionally evocative to look at. (See top left of Figure 15.) Colors, on the other hand, are notoriously evocative–people have strong preferences regarding the colors of their clothes, cars, and houses, and we sense strong associations between color and emotions. I have argued in my research and in The Vision Revolution that color vision in us primates–our new‑to‑primates red‑green sensitivity in particular–evolved to detect the blood physiology modulations occurring in the skin, which allow us to see color signals indicating emotional state and mood. Color vision in us primates is primarily about the emotions of others. Color is about humans, and it is this human connection to color that is the source of color’s evocativeness. And although, unlike color, writing is not generally evocative, not all writing is sterile. For example, “V” stimuli have long been recognized as one of the most evocative geometrical shapes for warning symbols. But notice that “V” stimuli are reminiscent of (exaggerations of) “angry eyebrows” on angry faces. Color is “about” human skin and emotion, and “V” stimuli may be about angry eyebrows–so the emotionality in each one springs from a human source. (See top right of Figure 15.) We see, then, that the nonevocative visual signs look like opaque, not‑necessarily‑human objects, and the evocative visual signs look like human expressions. I have summarized this in the top row of the table in Figure 15.

Figure 15 . Evocative stimuli (right column ) are usually made with people, whereas nonevocative stimuli (left column ) are more physics‑related and sterile.

Do we find that evocativeness springs from the same human source within the auditory domain? Let’s start with speech. As we discussed in the previous chapter, speech sounds like solid‑object physical events. “Solid‑object physical events” amount to a sterile physics category of sound, akin in nerdiness to “three‑dimensional world of opaque objects.” We are capable of mimicking lots of nonhuman sounds, and speech, then, amounts to yet another mimicry of this kind. Ironically, human speech does not sound human at all. It is consequently not evocative. (See the bottom left square of Figure 15 for speech’s place in the table.) Which brings us back to music, the other major kind of auditory stimulus people produce besides speech. Just as color is evocative but writing is not, music is evocative but speech sounds are not. This suggests that, just as color gets its emotionality from people, perhaps music gets its emotionality from people. Could it be that music, like Soylent Green, is made out of people? (Music has been placed at the bottom right of the table in Figure 15.)

If we believe that music sounds like people, then we greatly reduce the range of worldly sounds music may be mimicking. That amounts to progress: music is probably mostly not about birdsong, wind, water, math, and so on. But, unfortunately, humans make a wide variety of sounds, some in fundamentally different categories, such as speech, coughs, sneezes, laughter, heartbeats, chewing, walking, hammering, and so on. We’ll need a more specific theory than one that simply says music is made from people. Next, though, we ask why there isn’t any purely visual domain that is as exciting to us as music.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 987;