Blind Joggers

Joggers love their headphones. If you ask them why, they’ll tell you music keeps them motivated. The right song can transform what is by all rights an arduous half hour of ascetic masochism into an exhilarating whirlwind (or, in my case, into what feels like only 25 minutes of ascetic masochism). Music‑driven joggers may be experiencing a pleasurable diversion, but to the other joggers and bikers in their vicinity, they’re Tasmanian Devils. In choosing to jog to the beat of someone else’s drum rather than their own, headphone‑wearing joggers have “blinded” themselves to the sounds of the other movers around them. Headphones don’t prevent joggers from deftly navigating the trees, stumps, curbs, and parked cars of the world, because these things can be seen as one approaches them. But when you’re moving in a world with other movers, things not currently in front of you can quickly arrive in front of you. That’s when the headphoned jogger stumbles . . . and crashes into the crossing jogger, passing biker, or first‑time tricycler.

These music‑blinded movers may be a menace to our streets, but they can serve to educate us all about one of our underappreciated powers: using sound alone, we know where people are around us, and we know the nature of their movement. I’m sitting in a coffee shop as I write this, and when I close my eyes, I can sense the movement all around me: a clop of boots just passed to my right; a person with jingling keys just walked in front of me from my right to my left, and back again; and the pitter‑patter of a child just meandered way out in front of me. I sense where they are, their direction of motion, and their speed. I also sense their gait, such as whether they are walking or running. And I can often tell more than this: I can distinguish a brisk from a shuffling walk, an angry stomp from a happy prance; and I can even recognize a complex behavior like turning and stopping to drop a dirty tray in a bin, slowing to open a door, or reversing direction to fetch a forgotten coffee. My auditory system carries out these mover‑detection computations even when I’m not consciously attending to them. That’s why I’m difficult to sneak up on (although they keep trying!), and why I only rarely find myself saying, “How long has that cheerleading squad been doing jumping jacks behind me?!” That almost never happens to me because my auditory system is keeping track of where people are and roughly what they’re doing, even when I’m otherwise occupied.

We can now see why joggers with ears un encumbered by headphones almost never crash into feral dogs or runaway grandpas in wheelchairs: they may not see the dog or grandpa, but they hear their movement through space, and can dynamically modulate their running to avoid both and be merrily on their way. Without headphones, joggers are highly sensitive to the sounds of cars, and can track their movement: that car is coming around the bend; the one over there is reversing directly toward me; the one above me is falling; and so on. Joggers in headphones, on the other hand, have turned off their movement‑detection systems, and should be passed with caution! And although they are a hazard to pedestrians and cyclists, the people they put at greatest risk are themselves. After a collision between a jogger and an automobile, the automobile typically only needs a power wash to the grille.

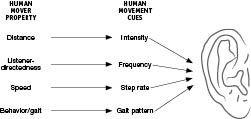

How does your auditory system serve as a movement‑tracking system? In addition to sensing whether a mover is to your left or right, in front or behind, and above or below–a skill that depends on the shape, position, and number of ears you have–you possess specialized auditory software that interprets the sounds of movers and generates a good guess as to the nature of the mover’s movement through space. Your software has evolved to give you four kinds of information about a mover: (i) his distance from you, (ii) his directedness toward (or away from, or at an angle to) you, (iii) his speed, and (iv) his behavior or gait. How, then, does your auditory system infer these four kinds of information? As we will see in this and the following chapters, (i) distance is gleaned from loudness, (ii) directedness toward you is cued by pitch, (iii) speed is inferred by the number of footsteps per second, and (iv) behavior and gait are read from the pattern and emphasis of footsteps. Four fundamental parameters of human movement, and four kinds of auditory cues: (i) loudness, (ii) sound frequency, (iii) step rate, and (iv) temporal pattern and emphasis. (See Figure 13.) Your auditory system has evolved to track these cues because of the supreme value of knowing what everyone is doing nearby, and where.

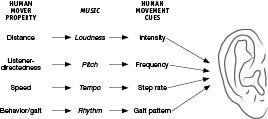

This is where things get interesting. Even though joggers without headphones are not listening to music, their auditory systems are listening to fundamentally music‑like constituents. Consider the four auditory movement cues mentioned just above (and shown on the right of Figure 13). Loudness? That’s just pianissimo versus piano versus forte and so on. (This is called “dynamics” in music, a term I will avoid because it brings confusion in the context of a movement theory of music.) Sound frequency? That’s roughly pitch. Step rate? That’s tempo. And the gait pattern? That’s akin to rhythm and beat. The four fundamental auditory cues for movement are, then, mighty similar to (i) loudness, (ii) pitch, (iii) tempo, and (iv) rhythm. (See Figure 14.) These are the most fundamental ingredients of music, and yet, there they are in the sounds of human movers. The most informative sounds of human movers are the fundamental building blocks of music!

Figure 13 . The four properties of human movers (left) are inferred from the four respective auditory stimuli (right) .

Figure 14 . Central to music are the four musical properties in the center column, which map directly onto the auditory cues for sensing human movement.

The importance of loudness, pitch, tempo, and rhythm to both music and movement is, as we will see, more than a coincidence. The similarity runs deep–something speculated on ever since the Greeks[1]. Music is not just built with the building blocks of movement, but is actually organized like movement, thereby harnessing our movement‑recognition auditory mechanisms. Headphoned joggers, then, don’t just miss out on the real movement around them–they pipe fictional movement into their ears, making them even more hazardous than a jogger wearing earplugs.

Much of the rest of this book is about how music came into the lives of us humans, how it gets into our brains, and why it affects us as it does. In short, we will see that music moves us because it literally sounds like moving.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 977;