The First Was a Doozy

While it is true that all physical interactions cause ringing, the ringing need not be audible, a point that already came up in the section called “Two‑Hit Wonder.” In this light, we need to ask, where in events are the rings most audible ? Consider the generic pen‑on‑table event again. The beginning of that event–the audible portion of it, starting when the pen hit the table–is where the greatest energy tends to be, and the ring sound after the first hit will therefore tend to be the loudest. If the pen bounces and hits the table again, the ring sound will be significantly lower in magnitude, and it will be lower still for any further bounces. Because energy tends to get dissipated during the course of an event, rings have a tendency to be louder earlier in the event than later in the event. This is a tendency, but it is not always the case. If energy gets added during the event, ring magnitude can increase. For example, if your pen bounces a couple of times on the table, but then bounces off the table onto the floor, then the floor hit may well be louder than the first table hit (gravity is the energy‑adding culprit). Nevertheless, in the generic or typical case, energy will dissipate over the course of a physical event, and thus ringing magnitude will tend to be reduced as an event unfolds. Therefore, the audibility of a ring tends to be higher near the start of an event; or, correspondingly, the probability is higher later in an event that a ring might not be audible.

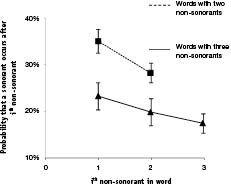

If language is instilled with physics, we would accordingly expect that sonorant phonemes are more likely to follow a plosive or fricative near the start of a word, and are more likely to go missing near the end of a word. This is, in fact, the case. Figure 10 shows how the probability of a sonorant following a non‑sonorant falls as one moves further into a word, using the same data set mentioned earlier. For example, words like “pact” are not uncommon in English, but words like “ctap” do not exist, and are rare in languages generally.

Figure 10 . This shows that sonorant phonemes are more probable near the starts of words, namely just after the first non‑sonorant (usually a plosive). The square data are for words having two non‑sonorants, and the triangle data for words having three non‑sonorants.

We have begun to get a grip on how hits, slides, and rings occur within events, but we have only considered their probability as a function of how far into the event they occur. In real events there will be complex dependencies, so that if, say, a slide occurs, it changes the probability of another slide occurring next. In the next section we’ll ask, more generally, which combinations of hits and slides are common and which are rare, and then check for the same patterns in language.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 855;