In the Beginning

The Big Bang is the ultimate event, and even it illustrates the typical physical structure of events: it started with a sudden explosion, one whose ringing is still “heard” today as the background microwave radiation permeating all space. Slides didn’t make an appearance in our universe until long after the Bang. As we will see in this section, hits, slides, and rings tend to inhabit different parts of events, with hits and rings–bangs–favoring the early parts.

To get a feeling for where hits, slides, and rings occur in events, let’s take a look at a simpler event than the one that created the universe. Take a pen and throw it onto a table. What happened? The first thing that happened is that the pen hit the table; the audible event starts with a hit. Might this be a general feature of solid‑object physical events? There are fundamental reasons for thinking so, something we discussed in the earlier section, “Nature’s Other Phoneme.” We concluded that whereas hits can occur without a preceding slide, slides do not tend to occur without a preceding hit. Another reason why slides do not tend to start events is that friction turns kinetic energy into heat, decreasing the chance for the slide to initiate much of an event at all. So, while hits can happen at any part of an event, they are most likely to occur at the start. And while slides can also happen anywhere in an event, they are less likely to occur near the start. Note that I am not concluding that slides are more common than hits at the nonstarts. Hits are more common than slides, no matter where one looks within solid‑object physical events. I’m only saying that hits are more common at event starts than they are at nonstarts, and that slides are less common at event starts than they are at nonstarts.

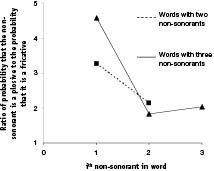

Is this regularity about the kinds of interaction at the starts and nonstarts of events found in spoken language? Yes. Words of the form bas are more common than words of the form sab (where, as earlier, b stands for a plosive, s for a fricative, and a for any number of consecutive sonorants). Figure 9 shows the probability that a non‑sonorant is a plosive (rather than a fricative) as one moves from the start of a word to non‑sonorants further into the word. The data come from 18 widely varying languages, listed in the legend. One can see that the probability that the non‑sonorant phoneme is a plosive begins high at the start of words, after which it falls, matching the pattern expected from physics. And, as anticipated, one can also see that the probability of plosives after the start is still higher than the probability of a fricative.

Figure 9 . This shows how plosives are more probable at the start of words, and fall in probability after the start. The y‑axis shows the plosive‑to‑fricative ratio, and the x‑axis the ith non‑sonorant in a word. The dotted line is for words with two non‑sonorants, and the solid line for words with three non‑sonorants. The main points are (i) that plosives are always more probable than fricatives, as seen here because the plosive‑to‑fricative probability ratios are always greater than 1, and (ii) that the ratio falls after the start of the word, meaning fricatives are disproportionately rare at word starts. These data come from common words (typically about a thousand) from each of the following languages: Japanese, Zulu, Malagasy, Somali, Fijian, Lango, Inuktitut, Bosnian, Spanish, Turkish, English, German, Bengali, Yucatec, Wolof, Tamil, Taino, Haya.

We just concluded that hits are disproportionately common at the starts of events in nature, and that this feature is also found in language. But we ignored rings. Where in events do rings tend to reside? In the previous section (“Nature’s Syllables”) we discussed the fact that rings do not start events, a phenomenon also reflected in language. How about after the start of a word? There would appear to be a simple answer: rings always occur after physical interactions, and so rings should appear at all spots within events, following each hit or slide.

But as we will see next, reality is more subtle.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 952;