THE GODS OF SEWAGE

Downstream on India’s Most Polluted River

After Sati killed herself, her husband was inconsolable. It was Sati who had convinced him to love, and who had taught him desire. It was for Sati that he had emerged from a life of austerity and isolation to be part of the world. And it was for his honor that she had thrown herself on the pyre.

He pulled her body from the fire and carried it for days, wandering, crazed with grief and rage. Because he was Shiva, and a god, his fury was destruction–a chaos that threatened to engulf the whole world. Vishnu went to calm him down, dismembering Sati’s corpse as Shiva carried it. (Gods have their ways.) People still worship at the places where Sati’s body parts fell.

Empty‑handed, Shiva went to the river, to the Yamuna. Yamuna, daughter of the sun, twin sister of death, goddess of love and compassion. He bathed in the river, and as the madness of his grief cooled, it scorched the water black.

This, they say, explains the color of the Yamuna–so distinct from the milky waters of the Ganges. The holy Yamuna is a river that accepts and dilutes grief and rage, a fount of love and understanding for everyone from the gods on down. Maybe it is mythologically appropriate, then, that it accepts so much else.

India is full of holy rivers, and even derives its name from a river. It is the land beyond the Indus, a river whose own name, just to be safe, derives from an ancient Sanskrit word for river. And as with Hindu deities, so with Indian waterways. The name of the game is multiplicity. Each is the incarnation or avatar or consort or child of every other, and there is hardly a creek in the subcontinent that can escape the burden of some pretty hard‑core metaphysical freight. How holy are India’s rivers? So holy that even certain bodies of water in Queens are also holy. So holy that you can’t spill your drink without worrying that someone will show up to venerate it.

The Ganges–or Ganga, as it is called in India–is, by many accounts, the holiest of all. Heart of Varanasi, consort of Vishnu, flowing through the hair of Shiva, etc., etc. It is the apotheosis and parent of all other rivers. And it was on the Ganga’s banks, nearly a decade earlier, that I had first seen the light as a pollution tourist. I had lived in New Delhi for six months and had happened to visit Kanpur, where the Ganga received a crippling infusion of industrial effluent and municipal sewage. It was supposedly the most polluted city in India. But I liked visiting Kanpur. I liked how you could walk from the tanneries to the river, from the open sewers to the farms, and see for yourself how they were all connected. I liked how you could stand on the banks of the reeking Ganga, almost as sludgy as it was holy, and watch pilgrims take their holy baths, confident in the purifying power of the impure water. All this, and cheap hotels. Yet in the guidebooks, Kanpur didn’t exist.

Well that’s not fair, I’d thought.

And in Delhi, I had met a different species of environmentalism from that in the United States. Back home, however much you thought you cared about the environment, it was an impersonal concern. After all, your daily surroundings, whether in suburb or city, were likely to be pleasant, or at least clean, or at least nontoxic. In India, though, environmentalism was more than an abstract moral value. It was more than a way to signal your politics and your socioeconomic status. Here, in the daily confrontation with poor air and adulterated drinking water, it took on the urgency of a civil rights struggle. Only in the polluted places could you properly understand what was at stake.

This time I skipped Kanpur. Skipped Ganga. It might be India’s holiest river, but the Yamuna is its most polluted, and I had priorities. I wanted to know why, with all the Hindu rumpus about rivers, a river goddess can’t actually catch a break. For although the Yamuna might be a goddess, by the time she leaves Delhi, she is no longer a river.

I hadn’t gone home. I had none. I had come straight from China. From Linfen to Beijing, from Beijing to Shanghai, from Shanghai to Delhi. Delhi, where, not five minutes from the airport, the cabdriver resumed where the Han family had left off.

“You are married?” he asked.

Had entire continents been populated only to make me say it? I was alone. Not with the Doctor, not newly married, but alone, and alone, and alone.

“No,” I said. “Are you?”

He nodded. He had a child, too.

“Your country, all love marriages. No arranged marriages. This is good,” he said. “Arranged marriage, father and mother choose the girl. You choose different girl.”

“You had an arranged marriage?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“Do you love your wife?”

“Yes,” he said. His eyes were on the road. “But I loved another woman.”

India. Land of contrasts.

That’s what you’re not supposed to write about India. But nobody can help it. Even the most sophisticated people will write thoughtful, evocative prose that still amounts to India, land of contrasts. What are they trying to say? Is there no contrast anywhere else in the world? I think what they mean is India, less tidy and homogenous than I’m used to.

I had loved Delhi when I’d lived here. Loved the noise, the smells, the energy of the street. That’s what I wrote home about. I had reveled even in the simple tumult of buying a train ticket. But as the truism has it, a traveler’s writings say more about the traveler than about the place traveled to. Before, I had found dusty blossoms of curiosity and independence on every corner. Now, years later, I saw Delhi again and wondered if I could just sleep through it. Through drab, mediocre Delhi.

But it wasn’t just me. Delhi had changed in the past decade. At least, that’s what people told me.

“Oh!” they would say. “Delhi has changed so much!” Even the autorickshaw drivers, if they spoke English, would tell me how bad the traffic had become, as if there were no traffic jams in Delhi in 2002. And those same autorickshaw drivers still pouted when you tried not to let them rip you off as fully as they wanted.

So Delhi was still recognizably Delhi. But it was true–there had been some restyling. Its elite shopping malls more convincingly suggested that you might be in America. The Evergreen Sweet House restaurant now had three floors, and air‑conditioning. The city’s upscale neighborhoods were marginally tidier than before, and disappointingly free of wildlife. Street animals used to be half the fun in Delhi, but now you’ve got to work to bring your clichés to life, and you’re down by Tughlaqabad before you can find a pair of cows blocking the road.

The most obvious change was the Delhi Metro, whose routes had burrowed through the city far more rapidly and effectively than anyone could have expected. It now ran all the way down to the satellite city of Gurgaon, about ten miles to the southeast. A subway to Gurgaon, imagine! The success of the Metro seemed to have taken the city by surprise. In a land where public works are so often lumbering, ineffectual, and corrupt, the subway was clean, efficient, and cheap.

As for the Yamuna, I had no idea if it had changed. Its banks lay only a few miles from where I had lived, but at the time I had been only dimly aware that a river even existed in Delhi. It was an appropriate ignorance, though. Delhi had long since turned its back on the Yamuna. Now the river played a part in the city’s life only as an object of neglect and disgust.

On the riverbank, I gave a man called Ravinder a few hundred rupees and we went out in his flat‑bottomed wooden rowboat. Sitting next to Kakoli, my translator for the day, I peered over the edge as Ravinder worked the oars. The surface of the water was a dark gradient of billowing grays interrupted by little bubbles. Methane, I assumed. We coasted into a stretch of water spread with an unfamiliar film, not quite as colorful as a petroleum rainbow, not quite as thick as the skin of milk on a boiling pot of chai. Lumpy black gobbets dotted its surface. We needed only our noses to understand that the water was dark with more than Shiva’s grief. We were floating not on a river, but on a great urban outflow, a stream of human sewage that was standing in for the river that had dug the channel.

The Yamuna was full of shit.

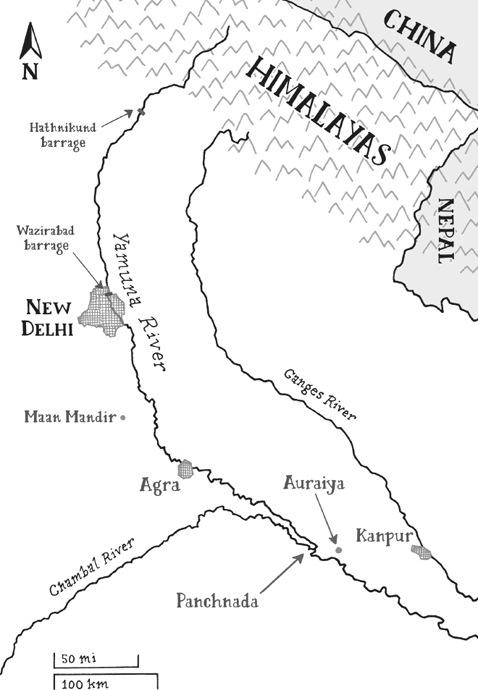

It gets this way in stages. Emerging clean from the Himalayas, the river receives periodic doses of sewage and industrial runoff as it crosses the plain. Then, about 140 miles upstream from Delhi, it meets the Hathnikund Barrage–a multi‑gated dam built to control the river’s flow. At Hathnikund, the greater part of the river’s water is diverted into the Eastern and Western Yamuna Canals. These canals, both hundreds of years old, were originally devised for irrigation, but an increasing amount of the water they divert is used for city water supplies, especially Delhi’s. The city’s population has grown more than 600 percent over the past fifty years, drastically increasing its water use.

In India, as in so many places, tension over water is the driving force behind an incredible swath of environmental and political problems. In this case, to make up for water spirited away by the megalopolis downstream, farmers in the region pump massive volumes of groundwater. The overextraction is so intense that it has lowered the water table to below the level of the riverbed itself, meaning that south of Hathnikund, the Yamuna simply percolates straight into the ground. The river runs dry. Except during the several months of the monsoon, the Yamuna essentially ceases to exist as it approaches Delhi.

Because it would otherwise disappear into the riverbed, water extracted for Delhi is transported via the Munak Escape, a fork of the Western Yamuna Canal that itself receives a helping of industrial waste and domestic sewage. The water then collects behind the Wazirabad Barrage, on Delhi’s northern margin. (Here it is augmented with water brought from the Ganga, of all places, making the Ganga a tributary of one of its own tributaries.)

Thanks to these inputs, there is water in the river at Wazirabad. But this water does not flow south into Delhi, as the river once did. Instead, it is pumped out and treated, becoming the basis of the city’s water supply.

Nevertheless, there is water downstream of the Wazirabad Barrage, flowing the fourteen miles through the heart of Delhi. For this stretch, the Yamuna takes the city itself as its source, receiving something close to a billion gallons of wastewater each day, the vast majority of it domestic sewage, and more than half of it completely untreated.

So when local activists refer to the Yamuna as a sewage canal, as they do, it is no figure of speech. Except during the monsoon, there would be no river in Delhi without this wastewater.

Nor is it much of an exaggeration when people refer to the Yamuna as dead. The river’s level of dissolved oxygen (a good indicator of its capacity to sustain life) here falls to approximately one‑tenth of the minimum government standard. Coliform levels (which indicate a waterway’s microbial danger) are incredibly high. The Indian government’s upper limit for safe bathing is five hundred coliforms per hundred milliliters of water. At points in Delhi, though, the coliform count has exceeded seventeen million.

The oarlocks squeaked and knocked as Ravinder worked the oars. He wore a Levi Strauss T‑shirt and blue track pants. The lifeless river was placid, almost pleasant. A light breeze took the edge off the sewage smell.

“Who told you this is water?” he said. He told us that when he was young, he had been able to see to the bottom of the river. Now, though, you could barely see a foot deep, and clouds of inky muck eddied against the surface as we passed through shallow areas, the ends of the oars black where they had touched the bottom.

Ravinder had grown up on the banks of the Yamuna, and still lived in one of the city’s few riverfront neighborhoods. And in his thirty‑odd years he had seen the river change. “There were lots of tortoises, but people sold them off. There were fish, and snakes,” he said. “But now it’s just a drain.” Although he lived mere steps away from the river, he neither bathed in it nor allowed his family to. Only in July and August, during the annual floods of the monsoon, would they get in the water. “During that period, the river becomes very beautiful,” he said. “But within a month, it’s over.”

Ravinder earned his money by taking people out to the center of the river to drop offerings or cremation ashes in the water. Sometimes he made a thousand rupees in a day–about twenty dollars. Sometimes he made nothing.

“I took two people out on the river earlier today to drop eighty kilos of charcoal in the water,” he said. “A priest told them to. They invoked the name of the sun, and of Yamuna, and dropped handfuls of charcoal into the river. Then they dumped the rest out of the bags. Tomorrow morning, I’m taking a couple to put a hundred and twenty fish into the river.”

“Living fish?” I asked.

“Living fish,” he said.

Kakoli shook her head. “Those fish will die.”

A printed picture of a blue‑skinned deity came floating downstream. Before I could make out if it was Shiva or Krishna, the oar struck it on the downstroke, folding the image and plunging it into the black water.

A pair of men were bathing on the riverbank. A gull flew over our heads. Upriver we saw a hawk, a tern. Over Ravinder’s right shoulder, Nigambodh Ghat was coming into view–the cremation ground. A trio of pyres burned on the shore, braiding the air into thick tangles of heat.

The cremation ground is one of the few lively spots on the riverside, and a surprisingly relaxing place to spend the morning. Kakoli and I had visited before going downriver to find Ravinder. We had sat on a large concrete step and watched a group of young men build one of the pyres now burning. (There was a gas‑fired crematorium just down the bank, but no person in his right mind wants to be cremated in a dank, indoor, gas crematorium. Not if your family can afford the wood to burn you on the riverbank.)

On a low pallet, a man lay wrapped in white cloth, his head exposed. His face was old. He was dead. The younger generation dribbled water on him from a plastic bottle and sprinkled dirt over his body. Then they finished building the pyre, leaning planks and branches against the man until they had formed a teepee of wood four or five feet tall. It was ten in the morning.

“In Calcutta, people still go to bathe in the river,” Kakoli said. “Even wealthier people. But in Delhi, people will not look at it. People will only come to the river to use it as a cremation ground.”

A young man in black trousers and a red sweater walked around the pyre, holding a thin strip of burning wood. It was the dead man’s son, I assumed. He stopped at the head of the pyre and lit it near the ground. A thin trail of smoke trickled out. That’s where we all go–not back to dust, but into the atmosphere, to join our emissions. The young man and his five companions then retired to one of the concrete tiers facing the bank and began their wait, chatting casually. It would take several hours for the pyre to burn.

Riding by the pyres in Ravinder’s boat, I now noticed a pair of men standing knee‑deep in the water, mucking out scoops of mud. They were collecting ashes that had been cast into the water from the riverbank. A cremated person may have been wearing rings, or been adorned with other precious objects, as they were placed on their pyre. Now these men were poring through their sodden ashes to see what they could find. Gold fillings, maybe?

I asked Ravinder if this wasn’t, you know, bad manners.

He frowned, looking at the men on the bank. No, he said. It’s not seen as disrespectful.

South of the cremation ground, we crossed wakes with a dark‑skinned woman wearing an olive‑colored sari. She was squatting on a large plastic bag stuffed with scraps of polystyrene foam and mounted with a square wooden frame. Her raft listed forward steeply to where she hunkered on its edge, working the water with a single, short oar.

Her name was Mamta. She lived with her husband on the opposite bank. They made their living combing the margins of the river for paper, plastic, anything they could sell to the recyclers. Her raft was littered with the morning’s haul: several coconuts, a few paper booklets, and a single plastic sandal.

She stared at the water as she answered my questions. They had been in Delhi for ten or fifteen years, she said. Eight years ago, the government had pushed them out of the shantytown they had lived in. Now, they lived in a temporary shack on the floodplain. When the river rose each year with the monsoon, they had to retreat with the land.

When I asked how old she was, she hesitated. “I don’t know,” she said. “But I think I’m twenty‑five or twenty‑six.” Then she continued upriver, raking her oar through the mat of flowers and trash that clung to the bank.

Ravinder sent us back out to the middle of the river, where he left off rowing and let us drift. He crossed his legs and opened a packet of tobacco. “So many people migrated to Delhi,” he said. “The waste going into the river has grown and grown with the city. But Yamuna is one. It has not multiplied.”

He still believed in the river, though. Yamuna was a goddess, he said. He might go for a week and a half without earning any money at all–only to make up for it in a single day’s work. The Yamuna didn’t take, he said. It gave.

With that, he put some tobacco in his mouth and we drifted for a while longer, spinning quiet circles in the breeze.

Where there are rivers or lakes in India, there are ghats: wide riverfront stairs that lead down to the water. Ghats are an indispensable part of the sacred Hindu love affair with water, and through history they have been places for worship, and worshipful bathing, and non‑worshipful swimming, and for doing the laundry, and for cremating the dead–as at Nigambodh Ghat–and for pretty much anything else you might want to do at the riverside. But Delhi has few ghats. It is a city of sixteen million with barely any places, ghat or otherwise, where people interact with the river. I went looking for any that were left.

At the south end of its Delhi segment, the Yamuna is again made to jump its channel. The Okhla Barrage shunts it into the Agra Canal, through which it is destined to become the Taj Mahal city’s unenviable water supply. Just upstream of the barrage is the riverfront park of Kalindi Kunj. Unlike many riverfront parks, though, Kalindi Kunj offers no actual frontage to its river. A fence encloses the park, keeping visitors away from the actual river, which sits quiet and littered with trash. Ill‑disposed to climb an eight‑foot‑tall fence topped with spikes, I resigned myself to wandering the leafy confines of the park.

The place was crawling with young couples in the throes of passionate hand‑holding. With every corner I turned, I almost stepped on a pair of sweethearts. In a city where young couples have no apartments or cars of their own to disappear into, they go to the parks. It is so common here for couples to meet each other in parks or at historical monuments that it sometimes seems that these places have been designated by the city government as official make‑out spots.

It ought to have sent me into a lovelorn tailspin, like everything else did. Instead, it was a respite. Since arriving in Delhi, I had been preoccupied with how Indian men and women interacted in public–or how they didn’t. It’s safe to say that the vast majority of Indians live under very conservative sexual mores, and it had been depressing the hell out of me.

Maybe it was the astounding numbers I had recently heard about child sexual abuse in India. The country is home to more than four hundred million children, nearly a fifth of the world’s below‑eighteen population, and according to the government more than half are sexually abused. Incredible India, land of contrasts, awash in brutality.

I thought of this every time I boarded the Delhi Metro. There are separate cars for men and women–which itself says something–and as we filed on, I would think of those children growing up, of what my fellow male passengers must be carrying inside them, and of what they must have done, and of hundreds of millions of lives distorted by such epidemic violence and rape. By the time the train left the station, I’d have convinced myself that men were born only for cruelty, and that no living person, woman or man, would ever escape our planet‑eating vortex of betrayal and isolation.

I was down.

In Kalindi Kunj, though, it was different. Maybe there was hope–just a little–for loving coexistence between the human species. Every second tree hosted a couple that sat at its base, talking quietly, laughing, holding hands, kissing. Everyone was running their hands through someone’s hair. Everyone was cradling the head of their beloved in their lap. If the woman wore a sari, she might drape its veil over both their heads. Who knows what went on in those micro‑zones of privacy? Everyone was smitten. On a perfect spring day, thirty yards upwind from the shittiest stretch of river in the world, I believed in love for a little while.

There once were ghats up by the ISBT highway bridge, but for no good reason the city government ripped them out in the early 2000s. Now the overpass itself serves as a kind of high‑altitude, drive‑thru ghat. As on other bridges over the river, people pause day and night to throw offerings or trash into the water. It’s hard to tell the worship from the littering.

My friend Mansi brought her camera, and we spent a morning underneath the overpass, where a slope of packed dirt led down to the river. Every minute or two, an untidy rain of flowers would sift down from the bridge, or a full plastic bag would hit the water with a dank plop. We would look heavenward, sometimes catching a motorcycle helmet peering down from the railing. The city government had erected fences on most bridges to keep people from throwing over so many offerings; invariably the fences become tufted with flowers and bags that snag as someone tries to throw them over. Here, though, people had found an unprotected spot where they could throw their offerings unhindered. It was the same kind of unceremonious ceremony that I had seen at the cremation grounds, a sacredness that had no use for aesthetics.

And as with the cremation grounds, anything of value that goes into the water here must also come out. Wherever offerings are made, there are coin collectors, men who scour the river bottom with their hands. Although they are called coin collectors, they are comprehensive in their religious recycling, and actually collect anything that can be sold or reused.

The sun had just come up, murky over the Yamuna, and on the bank four collectors were finishing their morning chores before getting down to work.

“In the summer,” one of them told me, “the smell gets so strong here, your eyes water.” His name was Jagdish, and he had been in the reverse‑offering business for nearly twenty years, since he was a teenager. He made enough to support his wife and ten‑year‑old daughter.

Jagdish reeled off a list of what you could find in the water here: gold and silver rings, gold chains hung with devotional pendants, coins with images of gods. But only once in a while was the score so good. “If that happened every day,” he said, “I wouldn’t be here.” When he found coal, he sold it to the men who ironed clothes on the side of the road. When he found paper, he sold it for recycling. Coconuts he sold to people to sell on the street, or to be pressed for coconut oil if they were dry.

When you make an offering to the Yamuna, then, you are not making a permanent transfer of spiritual wealth, but playing part in a cycle, leaving tributes that will go into the river this morning only to be fished out, sold again, and reoffered this afternoon.

Jagdish worked this part of the riverbank with his brother and two other men, and while Jagdish lived five or six kilometers away, his brother Govind lived here by the water, in a tiny, tent‑like shack. Govind, a friendly man in a green baseball cap, was also in his late thirties. He explained that because the water was too dark to see through, the collectors worked by touch, bringing handfuls of mud off the bottom to inspect. Govind wasn’t a good swimmer, so he only waded in to his neck. His brother did the diving, when it was necessary.

A bag of trash or offerings dropped from the overpass. In the dirt, Jagdish’s pet monkey, Rani, was lying on top of his dog, Michael. Rani idly scratched the snoozing dog’s stomach, a picture of interspecies peace. This was the kind of symbiotic friendship the human race needed with the rest of the natural world, I thought. But then Rani started picking at Michael’s anus, and he snarled and kicked her off.

Like the boatman Ravinder and the workers at the cremation grounds, Jagdish and Govind and their colleagues were among the last people in Delhi for whom the Yamuna was a life‑giver not merely in a spiritual sense but in a practical one. And Govind told us he liked the work. “We’re our own boss,” he said. “We go in whenever we want. We’re here tension‑free.”

When I asked him if he was religious, he shrugged. “Because the world follows God, we have to follow God, too,” he said. I wasn’t sure if that meant he was a devotee or not. Did they make offerings? He waggled his head. Sometimes they would give flowers or incense. But that was it.

“We take it out,” he said. “We don’t put it in.”

India’s credentials as a pollution superpower go beyond its rivers. There are the astounding shipbreaking beaches of Alang, and the lead smelters of Tiljala. And let’s not forget Kanpur, with its tannery effluent, rich in heavy metals. All of South Asia, really, is a wonderland of untreated toxic waste. And while India’s per capita carbon emissions are still low, its growing economy and the fact that there are 1.2 billion of those capitas mean that it is still a huge source of climate‑changing gases.

The irony is that, in terms of environmental law, India is extremely advanced. Its very constitution mandates that “the State shall endeavour to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forests and wildlife of the country.” As if that weren’t enough to make an American environmentalist weak at the knees, it goes on to declare that “it shall be the duty of every citizen of India to protect and improve the natural environment, including forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife, and to have compassion for living creatures.” And it’s backed up by an activist supreme court that issues binding rulings on specific problems. Sounds like paradise.

Yet the results aren’t great. Bharat Lal Seth, a researcher and writer at the Delhi‑based Centre for Science and Environment, told me that although the court system is activist, this is merely because the executive branches of government shy away from taking action, leaving it to the judiciary to issue edicts. But rulings are useless on their own.

“The judiciary feeds the [environmental] movement, and the movement feeds the judiciary,” Seth said, sitting in CSE’s open‑air lunchroom. “You get a landmark ruling, and…what’s going to come of it?” The very fact that the Indian government doesn’t feel threatened or bound by such decisions makes it easier for the court to issue them.

Seth had put me in touch with R. C. Trivedi, a retired engineer from the Central Pollution Control Board, who joined us in the CSE canteen. He was a small, friendly man with rectangular glasses and a short, scruffy beard, and probably knew more about the Yamuna’s problems than anyone else in the country. Even after a thirty‑year career, he exuded enthusiasm for the details of India’s water supply and wastewater system. He smiled when he talked.

Before long, Trivedi was sketching a tangled diagram of the Yamuna in my notebook, reeling off numbers for biochemical oxygen demand and flow rate, and marking off the river’s segments, from the still‑flourishing Himalayan stretch, to the dry river below Hathnikund, to the Delhi segment–“basically an oxidation pond,” he said–and finally the “eutrophicated” lower stretch, where the nutrients from decomposing sewage lead to algae blooms and oxygen depletion. “A lot of fish kill, we observe,” he said, tapping on his newly drawn map. The eutrophicated segment runs for more than three hundred miles, until finally the Chambal, the Banas, and the Sind Rivers join it. There, he said, “it is good dilution. After that, Yamuna is quite clean.”

Listening to Trivedi and Seth, I could see that the brutal irony of the Yamuna’s situation was not only that its holiness did nothing to protect it, nor that India’s tradition of environmental law was so out of joint with the actual state of its environment. The worst part was that, incredibly, cleaning up the country’s rivers had for years been a major government priority. There was the Ganga Action Plan (or GAP, begun in 1985), and the Yamuna Action Plan (YAP, 1993), and the National River Conservation Plan (1995), and YAP II (2005), and YAP III (2011), among many other programs and plans, many of which continue to this day. Such programs had received massive funding, more than half a billion dollars over the previous two decades. Most of it had been spent on the construction of sewage treatment infrastructure.

At best, it had been a vast reenactment of the coin collectors’ work, with the government pouring billions of rupees into the rivers, and builders of infrastructure standing by to dredge the money out.

The problem with this approach was that building sewage treatment plants was simply not enough. “We are spending huge amounts of money from the World Bank, from all other sources, taking loans,” Trivedi said. But little of the wastewater infrastructure created with that money actually worked. “You have taken the loan and created it, and they don’t have the money to operate it! It can work only when there is continuous flow of funds.” He shook his head, smiling. “When you create a sewage treatment plant, you first figure out how it will work for twenty or thirty years. But we never looked at that. We just implemented the YAP.”

“Which has no effect,” I hazarded.

“Which has no effect,” he confirmed.

Because Delhi doesn’t charge for sewage treatment, there is no flow of funds to sustain the treatment plants. Not that most people in Delhi could afford sewage treatment fees in the first place. A further problem is the helter‑skelter pattern of development in the city. A large proportion of Delhi’s neighborhoods have sprouted up unplanned, without any thought for how services like water and sewage treatment could be delivered, even if they were affordable. Sewage treatment plants built with YAP funds were therefore placed where there was room for the plants, not where there was sewage to be treated.

Trivedi thought any viable solution had to address the depletion of groundwater in the river basin. That meant promoting rainwater harvesting, a practice with deep traditional roots in India. Village ponds and earthen bunds can allow monsoonal water to stand long enough for it to seep into the ground and recharge the depleted water table. “Thereby, we can reduce the depletion of the groundwater table in the entire catchment area,” Trivedi said. “And if the water table comes up, all the rivers will start flowing again.”

Having told me how to heal every river in India, he put his hands on the table. There was, I knew, another shoe to drop.

The rainwater harvesting, I asked. Was that something that would happen at the local level?

“Yes,” he said. “But government always spends money on big, big projects. When people suggest something small, like five thousand dollars for a small reservoir or village pond…” He trailed off, still smiling. “They say, ‘No, no, no. This is very small.’”

The one place where Delhi retains a bit of the river life that it ought to have is Ram Ghat, which clings to the west side of the river immediately below the Wazirabad Barrage. It is behind this barrage, which doubles as a bridge to east Delhi, that the city’s drinking water supply collects.

Ram Ghat is a bank of broad stairs dropping precipitously to the river from a wooded area next to the road. The upstream edge of the ghat abuts the barrage, itself several stories tall. Thick concrete pylons support its roadway, with metal doors in between, to hold back the upstream part of the river. In monsoon season, large volumes of water are allowed through, but on the day Mansi and I visited, all the doors were closed but for one, and even it was open only a crack. Several boys laughed and swam in the minor waterfall that spilled from its edge. Because we were upstream of the sewage drains that emptied into the river, the water here was brighter and clearer, and free of those unmentionable floating clumps. On the far side of the river we could see modest fields of vegetables. There were small fields like this up and down the floodplain, even in Delhi.

At the top of the stairs, a man wearing office clothes bought a tiny tray of birdseed from a vendor, placed it in front of some ravens on the parapet, and prayed. On the submerged steps at the bottom, a boy lingered knee‑deep in the river, collecting plastic bags and scraps of wood. A few yards downriver, a woman heaved a two‑foot‑tall idol of Ganesh into the water. By the time his elephant‑headed form had disappeared under the surface, she was already starting the climb back, dusting off her hands as she went.

I walked down the tall stairs to the water. On the bottom step, a man in a white undershirt was dragging a magnet through the water. The coin collectors were innovating. “To live, you have to do something,” he said, in the universal wisdom offered to journalists who ask people about their humble, dangerous, or generally crummy jobs. And there were worse ways to spend your life than wandering up and down Ram Ghat in your shorts.

On the lowest step, I hunkered by the water. I wasn’t about to take a holy dip, as they call it, but this seemed like the cleanest spot on Delhi’s riverbank to get tight with the goddess of love. If it was good enough for Shiva, it was good enough for my tiny, writhing knot of a heart.

I put a hand in the water. Minute forms darted away. Water bugs. Something still lived in the Yamuna. Under the heat of the day, the river was cool against my skin. Coliform‑rich, but refreshing. I lifted a handful of water. How much of this was Ganga? How much from the Munak Escape? How much had diffused its way upstream from the nearest sewage outflow? I poured it over my head. Yamuna’s all‑encompassing love dribbled through my hair, down the back of my neck, and soaked into the collar of my shirt.

A woman with a big white sack landed heavily on the lower step. Her daughter was with her. Together they upended the sack. Flowers and small pots tumbled out, along with what looked like disposable food trays: the leavings of some devotion performed elsewhere, which would only be completed once they had drowned the ritual scraps. Another couple overturned a bag of charcoal. Hydrocarbon rainbows spread across the water. A pair of boys standing in the river immediately started picking out the hunks.

But coins and charcoal were not the only things that got fished out at Ram Ghat. At the top of the stairs, we met Abdul Sattar, sitting cross‑legged on a small rug he had rolled out on a shady bit of the parapet. He was in his mid‑forties, and wore a black sweatshirt and a pencil mustache.

Sattar was the self‑appointed lifeguard of Ram Ghat. By vocation he was a boatman, like Ravinder, but that was auxiliary to his real passion, which was pulling attempted suicides out of the river. He had been doing it for more than twenty‑five years.

With Mansi translating, I asked him if a lot of people tried to kill themselves there. He waved his head emphatically. “Bahot,” he said. A lot. We were only a week and a half into March, and there had already been two attempts this month.

“I didn’t let it happen,” Sattar said. “I can see them coming in. They generally look distressed.” He had a crew of youngsters who hung out by the river. Whenever he spotted someone who looked upset, he would direct his helpers to follow the person around, so a rescuer would be close at hand in the case of a suicide attempt.

Sattar provided his services for free. And why not? All he had to do was sit in the shade, greet passersby, enjoy the view, and occasionally save somebody’s life. But he told us his family didn’t like it. They didn’t like that he would invariably rush off to the river when called, even in the middle of the night.

“Are people upset when they realize you’ve kept them from killing themselves?” I asked.

There was a faint smile on his face. “Usually the women get very upset. But the family is grateful.” He said there were a lot of students who tried. There was always a rush after exam results came out. Others were motivated by family disputes.

“Do people kill themselves because they can’t marry who they want?” I asked.

He nodded. “Yes. There are plenty of love cases. It’s mostly students and lovers.”

He was staring at the barrage. I asked him whether he had ever lost anyone. He nodded without hesitation.

The defining moment of Sattar’s lifeguarding career had come on a cold, foggy November morning, nearly fifteen years earlier. A crowded school bus had come across the barrage from the east, the driver speeding in the fog. In those days, Sattar said, there was no fence on the bridge. The driver had veered to avoid a pile of sand in the roadway, and the bus skidded out of control and crashed over the downriver side of the barrage. It was seven‑fifteen in the morning.

“I dived in straight away,” he said, pointing at a spot of water twenty feet from the bank. “Three boats charged, as well.” The men dove and dove into the cold water, pulling kids to safety before going back to find more. Soon, they were finding only bodies.

“Now that I’m describing it to you, it’s right there in front of me,” Sattar said. “Everywhere we put our hands, we found them. Under the seats. I pulled out the body of one boy, and two others came with him.” Out of 130 children on the bus, nearly 30 died.

The Wazirabad crash was a huge news story in Delhi, and Sattar received an award from the national government. There had been promises of money, too, but Sattar told us that had just been the chatter of politicians trying to look generous. They had never followed up.

But he didn’t care. Lifeguarding was its own reward. He told us of one girl who had survived the crash. In a television interview, she had said it was thanks to Sattar that she was alive.

“I save lots of people,” he said. “I’ve gotten used to it. But when that girl said that, it really touched me.”

He shook his head, still deep in the memory. He had been shivering for a week, he said. The river had been very cold.

My original plan had been to find a canoe or a rowboat and run the Yamuna from Delhi to Agra, a journey usually made by bus. My waterborne arrival at the Taj Mahal–likely to a throng of local media–would open up an entirely new tourist route, and possibly lead to economic development along the water, and a renewed campaign to restore the Yamuna. You’re welcome.

But my delusions faded fast. Just you try looking up kayak in the Delhi yellow pages. And although there are scores of whitewater rafting companies in the foothills of the Himalayas, I soon realized it was hopeless to try to entice them out of the mountains. I didn’t have the money. Besides, they were whitewater rafters, not brown. Finally, there were all those dams on the Yamuna, and diversions, and dry sections. How do you raft a river that’s not there?

On foot is how. I had learned there was a yatra under way. Yatra is a Sanskrit word for “procession” or “journey,” and in this case meant a large protest march undertaken by a group of sadhus. Hindu holy men. They were walking a four‑hundred‑mile stretch of the Yamuna, from its confluence with the Ganga in Allahabad all the way up to Delhi, to demonstrate against the government’s failure to clean up the river. If I could find the march, out there in the wilds of the state of Uttar Pradesh, I could tag along for a few days. What luck! Environmentalism, spirituality, a good hike–and it was free. Knowing I’d need some Hindi on my side, I asked Mansi if she wanted to come along. She agreed right away. She’s a photographer, and photographers are always down for an adventure.

Before I left Delhi for the trip downstream, though, I went to see the source of the trouble.

The Najafgarh drain was once a natural stream, but even more than the Yamuna, it has been completely overwhelmed by its use as a sewage channel. With a discharge approaching five hundred million gallons a day, including nearly four hundred tons of suspended solids–yes, those solids–the single drain of the Najafgarh accounts for up to a third of all the pollution in the entire, 850‑mile‑long river. It is the Yamuna’s ground zero.

We approached it on foot, picking our way around the hubbub of a construction site. There was a new highway bridge going up, bypassing the chokepoint of the road over the Wazirabad Barrage. Beyond the work area we found a footbridge that crossed the drain several hundred yards up from where it met the Yamuna.

The footbridge was a wide dirt path bordered by concrete parapets. Looking over the edge, we could see the wide, concrete‑lined trough of the drain, perhaps two stories deep. A dark slurry surged along its bottom. The air nearly rang with the smell–that fermented, almost salty smell. Sewage. It was a smell somehow removed from actual feces. A smell that somehow distilled and concentrated whatever it is about feces that smells so bad.

I had smelled that smell before, but never had it smelled like it smelled that day at Najafgarh. It smelled so bad it gave me goose bumps. It smelled so bad it made my mouth water. The gag reflex scrambled up my throat, looking for purchase. I tried to take shallow breaths.

And yet.

I looked over the side again. Vegetation climbed the seams of concrete on the walls of the drain. Green, bullet‑headed parrots flew over the dark water. Pigeons stepped and dipped on a concrete ledge. Butterflies flopped upward through the sunny air.

Moving to the downstream side of the bridge, I saw strings of flowers snagged on the electrical wires that crossed the drain. They had caught there when people had thrown them in. Even here, people offered.

And why not? Underneath the stink and the noise, the rationale unfolded. This was a tributary of the Yamuna. Are you not to venerate it, merely because it smells? Why not worship it, suspended solids and all? What could be more sacred than a river that springs from inside your neighbor’s belly?

The temple of Maan Mandir stands on a craggy hill outside the small, tangled city of Barsana, seventy‑five miles south of Delhi. They worship Krishna there, and you could do a lot worse. Krishna comes in the guises of an infant‑god, a young prankster, a musician, an ideal lover, a fierce warrior, and–depending who you ask–an incarnation of the ultimate creator. With Krishna, you get it all.

Maan Mandir is the headquarters of Shri Ramesh Baba Ji Maharaj. Shri Ramesh Baba Ji–screw it, I’m just going to call him Shri Baba–was the guru who had launched the Yamuna yatra, and I had been granted permission to join the march on the condition that I visit him first. A reluctant guru‑visitor, I had agreed only grudgingly. I was impatient to fall in with the yatra. Images danced in my mind of contemplative Hindu ascetics walking the banks of the Yamuna downstream from Delhi–the oxygen‑starved, eutrophicated segment.

We had come to Braj, Krishna’s holy land. Braj straddles the boundaries of several Indian states, at the middle of the so‑called Golden Triangle formed by Delhi, Jaipur, and Agra, and is one two‑hundredth the size of Texas. It was here, way back when, that Krishna spent his days herding cows, stealing butter, and having sex with milkmaids.

So it is hallowed ground, and when you consider that almost every hill and pond and copse of trees in Braj is paired with a story of one of Lord Krishna’s frolics or flirtations, you begin to understand the environmentalist possibilities of Hindu belief. The very landscape of Braj is sometimes thought of as a physical expression of Krishna. And through it flows one of his lovers: the goddess Yamuna. In the temples of Braj, she is the holiest river of them all.

So the question isn’t why Shri Baba had launched the Yamuna yatra, but why he hadn’t done it sooner. Perhaps he was busy trying to protect the sacred hills and ponds of Braj. These were every bit as endangered as the Yamuna herself, and Shri Baba, in addition to pursuing a successful guru‑hood at Maan Mandir, had made local conservation into a specialty–restoring ponds, protecting forests, fighting illegal mining in the hills, and establishing retirement homes for cows. (Not so ridiculous if you think cows are sacred.)

The embodiment of deities and sacred history in the natural world would seem to give Hinduism a huge leg up on Christianity in the eco‑spirituality sweepstakes. St. Francis notwithstanding, Christianity has tended toward the anthropocentric. Our holy figures are all human, and live in the human sphere, which–some people argue–explains the West’s rapacious approach to its environment. Perhaps things would have been different if God had given Jesus the head of an elephant. And you know we Christians would have an easier time connecting to the rest of nature (and less trouble stomaching evolution) if there were a monkey in the Holy Trinity. Alas, we have no Ganesh, and no Hanuman.

Even worse, Christianity spent centuries promoting the idea that wilderness was either fodder for our dominion or a source of evil. The Devil was not in the details; he was in the woods. Of course, that’s not true anymore. Now, we love the woods, love nature, and save our fear and abhorrence for the dirty and despoiled places, precisely because they no longer count as natural. I guess that pent‑up Judeo‑Christian negativity had to go somewhere.

So, for a long time we were semiotically handicapped in the West, and there was no chance of us worshipping our forests. (What are you, an animist?) Besides, the world of forests and rivers and mountains was not the world that counted. All that mattered was the world that came after this one, a Kingdom that needed no conservation.

But don’t get all dewy‑eyed about the alternatives. It seems humanity will find a way to ruin its environment, whether or not it’s holy. The funny thing about vesting the physical world with divine meaning, as in Hinduism, is that the world can retain its sacred integrity whether or not it gets treated like crap.

Years earlier, in my visit to Kanpur, I had seen pilgrims taking bottles of Ganga water home with them to drink as a curative–a curative laced with sewage and heavy metals. When I asked one man about the quality of the water, he told me he wasn’t worried. “It can’t cause disease,” he said. “Because Ganga is nectar. It can’t be made impure.”

And because a holy river has such purifying power, it is actually the perfect recipient for all your most impure waste–sewage, corpses, and so forth–which by mere contact with the water will be cleansed. So there is no paradox in the state of India’s rivers after all. Their very holiness speeds their ruin.

From the crown of its ridge, Maan Mandir commands a blinding view of the surrounding plain. To the west is Rajasthan, hills rising against the horizon. Our media handler, a skinny sadhu called Brahmini, showed us around the temple and down to the lower buildings, where we would be staying that evening. His manner was gentle, almost shy, and although he spoke with a faint lisp, his English was good. He used it to provide a detailed and unceasing account of Shri Baba’s work.

“Shri Ramesh Baba Ji Maharaj is the greatest saint of Braj,” Brahmini said. “In fifty‑eight years, he never leaves Braj. When he came, there were robbers at Maan Mandir. They gave troubles to Shri Ramesh Baba Ji Maharaj. They threatened him and brought twelve guns. But Shri Ramesh Baba Ji Maharaj didn’t yield. He’s doing so many good works for India, specifically Braj. Braj has so many sacred places, but they are in a state of immense destruction.”

I perked up when he got to the Yamuna. “Yamuna River is also in very bad condition,” he intoned. “From New Delhi fresh water is not coming to Braj. It is stopped at the dam at Wazirabad. And instead of water, only stool and urine is coming to Braj. So yatra started two weeks ago in Allahabad, where Yamuna has confluence with Ganga. When yatra gets to New Delhi one month from now, millions of people will come to protest to the prime minister.”

Stool and urine, I scribbled in my notebook. Millions of people. Prime minister.

“Shri Ramesh Baba Ji Maharaj’s programs are not just for Braj,” Brahmini said. “Not just for all of India. But for all of the world.” He emphasized more than once that they accepted no money from the people who came to Maan Mandir, that free meals were given to all comers.

The most important part of their work, he said, was in the chanting of the holy names of God–specifically those of Krishna and of Radha, his lover and counterpart. Radha, milkmaid of milkmaids, was Krishna’s true love when he roamed the hills of Braj–never mind that she was married–and their relationship was so important to these particular followers of Krishna that they rarely spoke of one without the other.

“So much power is in the holy name of God,” Brahmini said. “You want to make sure that as many people hear the name of God as possible.” Maan Mandir had been distributing megaphones to devotees in small villages, so they could circulate through town every morning, chanting Hare Krishna, spreading the names of God. The program had reached thirty thousand villages so far.

I took a moment to mourn a million quiet village mornings ruined by amplified chanting. But Brahmini assured me it was worth it. “People and animals are salvated only by hearing it,” he said. “The entire atmosphere of the village is purified.”

Holy names could do more than purify village life. They were critical for the broader environment, a spiritual action necessary to confront the irreversible destruction predicted by scientists. “Only by chanting of holy names, the future and environmental problems can be saved,” Brahmini said. “He was a great environmentalist also, Lord Krishna was.”

In the evening we went to see Shri Baba preach. The sermon–or maybe it was a concert–took place in a breezy, square room in one of the buildings down the hill from the temple. The crowd was entirely Indian; Maan Mandir didn’t seem to be attracting any aging hippies or Silicon Valley dropouts. Shri Baba wandered in and sat on a low stage in front. He was in his late seventies but looked much younger. He had great skin. He was bald, with a perfect globe of skull that crowned an expressionless, hangdog face. He preached in Hindi, his voice low and strong, measuring his sermon with long pauses. As he talked, he noodled on an electric keyboard, and every now and then the music would take over, a drummer and a flutist would start up, and Shri Baba would shift seamlessly into song. His best move, which he pulled once or twice per song, was to let his melody soar into a high, long note: at this cue, the entire room would raise their arms and scream, an entire army of Gil Seriques. AAAGGHH!

Early the next day, we went to see the morning sermon up at the temple itself. Brahmini and Mansi and I climbed the stairs through the trees to the top of the ridge, toward an impossibly brilliant sky. Outside the temple, Brahmini led us into a small garden, in the middle of which stood the statue of a blue‑skinned woman. It was Yamuna herself, a faint smile on her face.

The temple was older and sparer than the buildings down the hill. It had a stone floor, cool under our shoeless feet, and unglazed windows looking out over the countryside. Mansi sat with the women, and Brahmini and I walked to a crumbling chamber adjoining the back of the room, where he could translate the sermon without disturbing everyone else. He had brought a handheld digital recorder, into which he would speak his translation. Later, he said, he would send the audio file to a devotee in Australia, who would transcribe it and post it on the Internet. They did this every day.

Shri Baba was sitting on another low stage facing the audience. He spoke. Brahmini leaned over to me so I could hear him as he murmured into the recorder.

“The greatest mental disease is attachment,” he said. “Suppose a man is attached to a woman.”

I sat up.

“Don’t see the outside,” Shri Baba told us. “See the inside. The body is full of bones, blood, urine, and stool. It gets old and dies.” Brahmini’s translation was rhythmic and precise. “There are nine holes in the body,” he said. “Only dirt and pollution is coming out. And think about that stool. ”

That was the key, according to Lord Krishna. “If you see the errors in the object, in the body,” Shri Baba said, “your attachment will be destroyed.”

I decided to give it a try. I thought about the Doctor, to whom I was still most abjectly attached. I thought about how she was full of stool and urine. About how she was nothing but flesh and bone. About how she would grow old and die. I saw her in a hospital bed, old and dying, full of stool and urine. A tourniquet of compassion seized me across the chest. My eyes filled with tears. It wasn’t working.

Shri Baba was still talking. He wanted to get some things straight about stool. He was, dare I say, attached to the topic. There were twelve kinds of it, he said, and proceeded to lay out the whole taxonomy, stool by stool. The body was a factory of stools, he said. It was folly to perfume and beautify something so polluted.

I know he was just trying to help his sadhus control their libido. But seriously, why so down on stool? Is our human plumbing really so vile? And wasn’t the Yamuna itself full of stool and urine?

I sat back, tuning out. As Shri Baba segued into a disquisition on lust, I watched two pigeons fornicate enthusiastically on a ledge above the doorway. A third pigeon arrived, and there was a fight, and then some more pigeon sex. It was hard to tell the sex from the fighting.

The sermon went on, in the gentle, alternating monotones of Shri Baba’s words and Brahmini’s translation. In a daze, I saw a fly circle out of the air and land on my forearm. I watched its head of eyes pivot back and forth. Then, hesitant, it lowered the mouth of its proboscis, and touched it to my skin.

“Baba is calling you,” Brahmini said, and we went in for our audience.

Shri Baba was sitting on a small dais in a long, bright chamber on the temple’s upper floor, profoundly expressionless, profoundly bald, cross‑legged. We put our hands together and sat at his feet. It was like the scene near the end of Apocalypse Now, when Martin Sheen meets Marlon Brando, except Shri Baba wasn’t scary like Colonel Kurtz, and it was daytime, and I wasn’t there to kill him. A dull roar of drumming and chanting emanated from downstairs.

He began talking in Hindi. I had feared he would tell us that only by the chanting of holy names could Yamuna be “salvated,” but I detected a practical mind‑set even before Brahmini started translating. Between my few words of Hindi and the language’s liberal borrowing of English, I could get the gist. Yamuna. Eighty percent. Water. Wazirabad. Twenty percent. Government not honest. No awareness.

Brahmini translated, and then indicated that I should ask some questions.

I told Shri Baba that I understood the Yamuna was important because of its connection to Krishna. But what about places Krishna had nothing to do with? What about the rest of the world? Did Shri Baba care only for Braj?

“The importance of environment is all over the world,” he said. “Without the non‑human life there is no human life.”

What Shri Baba really wanted to talk about was corruption. And he didn’t mean it in the spiritual sense. He said India was corrupt from top to bottom, especially as related to the environment. The supreme court had decreed that fresh water should come to Braj through the Yamuna, and yet it didn’t happen. The yatra’s purpose was to confront that fact.

“Not even 1 percent of India’s people think about purifying Ganga and Yamuna,” he said. “People who make efforts for sacred works are crushed.” He said a price had been put on his head during the fight to save the hills from mining. People had been kidnapped. Shri Baba had been poisoned.

He ran his hand over the dome of his head, his face still impassive. “But we don’t fear death,” he said. “I consider myself as dead.”

We found the yatra that night, ten or fifteen miles southeast of Auraiya. They were camping in a grassy compound off a minor rural highway. The river was nowhere in sight. The roads and paths along its banks, I was told, had become almost impassable, especially for the support trucks. Sunil, the march’s logistical manager, had chosen to take the yatra along Highway 2 for a little while. We’d get back to the Yamuna soon, he assured me.

It had taken us all day to get there. Mansi and I had traveled from Maan Mandir alongside a tall, dark sadhu with a grandly overgrown beard. He wore a plain white robe and his only possessions were a small digital camera and a nonfunctional cellphone. He had a kindly face, but we dubbed him Creepy Baba, for the way he kept trying to put his hand on Mansi’s knee.

The idea had been for Creepy Baba to help us find the yatra, but over the course of multiple jeeps, buses, and one badly crowded jeep‑bus, he proved blinkingly inadequate to the task. In Agra, he convinced us to board the wrong connecting bus, which we could only un‑board after a quick shouting match with the driver and most of the passengers.

Oh god, said Mansi. Who knows where Creepy Baba is taking us.

Sunil picked us up in Auraiya and drove us to camp, where a pod of sadhus descended on us in greeting. Through Mansi, they asked me over and over how I had found out about the yatra. When I said I had read about it in a newspaper, online, they wanted to know which newspaper. I had no idea.

“Was it the Times of India ?” asked one man.

I did know of the Times of India –and knew it was in English. “It could have been,” I said.

“Times of India !” he cried to the assembled crowd.

Soon a cellphone was thrust into my hand. When, moments later, it was snatched away, I had been interviewed by a newspaper in Agra. I know this because Mansi later read me an extensive quote–attributed to me, but none of which I actually said–from a Hindi‑language Agra daily.

The man who had asked me about the Times was called Jai. In Shri Baba’s absence, he was lead sadhu on the march. Shri Baba never leaves the land of Krishna, and so would join the yatra only when it reached Braj. The sadhus were carrying a pair of his shoes on the march, though, so he could be there in spirit.

Jai had been following Shri Baba for ten years now. A former social worker, he lived at Maan Mandir and was an almost frantically amiable man. In Hindi, he apologized for not speaking English. In English, I apologized for not speaking Hindi. Not to be outdone, he made an elaborate pantomime of seizing the air in front of my mouth, inserting it into his ear, and then raising his hands once more in apology.

No, I said. It is I who must apologize.

Conditions on the yatra were spartan but well managed. The tents were large, sturdy structures of green canvas, perhaps handed down by the British upon their departure in 1948. Each tent was strung with a single, blinding lightbulb hanging from an old wire connecting it to the generator. There was a steel water tank on a trailer, and a truck mounted with an oven for baking flatbread, and a crew of at least half a dozen guys whose job it was to drive ahead of the march, set up camp, and cook. All we had to do was walk.

There is a long tradition of political walking in India, and this particular yatra happened to coincide with the anniversary of Ghandi’s famous Salt March, the yatra of yatras. For more than three weeks in the spring of 1930, Gandhi and an ever‑increasing army of followers marched toward the sea, where they would make salt from seawater, symbolically violating the Salt Act imposed by Britain fifty years earlier. Along the way, Gandhi made evening speeches to the marchers and to the thousands of local people who came to investigate.

Covered widely in the international media, the Salt March gave a huge symbolic boost to the Indian independence movement, and put civil disobedience on the map as a major political strategy. The marches of the American civil rights movem

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-05-08; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 1245;