SOYMAGEDDON

Deforestation in the Amazon

The smell of smoke, a plume rising by the road, and then we saw the flames. The forest was on fire. “Stop! Stop!” Gil cried, and Mango pulled over. Adam and I waded through the brush and emerged into a world of ash and cinder.

We were in the Amazon rainforest. The former Amazon rainforest, to be exact. The broad field where we stood was empty, freshly scorched to the ground. The air swirled with cinders. They mixed with sudden clouds of small, attacking insects. Where had they come from? Was there a species of bug driven to riot by the smell of smoke?

At the edge of the field, we found the fire crawling over what was left to burn. It reared up in brief flares, as tall as we were, then ducked its head back toward the ground. Adam started videotaping.

I turned back to the field, a monochrome square a hundred yards to a side. A single massive tree stood alone in the ruin. The ground was warm through my boots. In front of me, long bands of white crossed the ground, dividing, and dividing again, growing thin. They were the ghosts of trees. Felled and burning, they had turned to ash where they lay. Ashen branches sprouted from ashen trunks. I kicked one and it rose into the air, a white eddy circling on the hot breeze.

Everyone knows forests are good and deforestation is bad. Forests are habitat. Forests absorb carbon dioxide and forestall global warming. But not everyone knows that cutting them down and burning them not only releases carbon dioxide into the air but also creates local feedback loops that cause the forest to die back even further, meaning more habitat loss and more CO2 emissions. The Amazon, at ten times the size of Texas, give or take a couple of Texases, has so much forest that to cut it back is to set off what some have termed a carbon bomb, with global consequences.

I had come to Brazil to see the burning fuse on that tremendous carbon bomb. There was only one catch: this probably wasn’t it. You could even argue that this blackened, boot‑melting wasteland, with its phantom trees and prowling flames, was protecting the forest from something even worse. Here, near the joining of the Amazon and one of its greatest tributaries, the people standing in the way of the rainforest’s destruction sometimes looked a lot like they were cutting it down, or setting it on fire.

India was supposed to be next. India, with the Doctor, married, for our honeymoon. But the Doctor had met me on the wharf when the Kaisei made San Diego, and called it off. A chasm opened in the ground and swallowed the world. It wasn’t me, she said. But still. No wedding. No marriage. My life evaporated in a single afternoon.

I took it hard. The global environment, formerly such a candy store of problems, now lost its appeal. Even climate change and mass extinction seemed pretty minor next to the growing monument of my heartache. Yet books must be written. Who would take up the gospel of pollution tourism if I let it drop? I ditched India for the meantime and made for the Amazon, a fugitive from my own despair.

My friend Adam came with me. Or maybe I should say that I went with him. Ostensibly he was coming so we could shoot a television news piece in Brazil. We had collaborated on that kind of work before. But I also suspected that, unlike me, Adam wanted to go to Brazil. He may have thought, too, that I could use a little support. Left to my own devices, I might spend the entire Amazon trip in a hotel room, under a mosquito net, watching whatever passes for cable TV down there.

Friends–they’re always trying to encourage you, and to convince you that you’re not incompetent and unlovable and doomed to failure. Why can’t they just butt out? On the other hand, with Adam on board, I could renounce all the detailed background research that I was going to blow off anyway. What was I going to do–crack open the Amazon with a week’s googling? Screw that.

Originally, the Brazil trip was going to be about beef. Cattle ranching has long been a major driver of deforestation in the Amazon. Surely there was some friendly rancher out there who would give us the inside scoop on how virgin rainforest gets turned into hamburgers. Just think of the steaks we would eat.

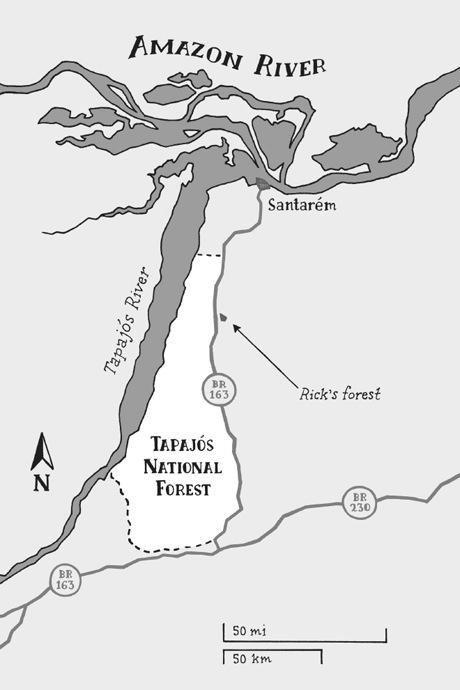

But then we found out about soy. That’s where the action was, we read (Adam read). Soy farmers were leveling great stretches of forest so they could sell animal feed to Europe. We ditched the ranching idea and chose Santarém as our destination. The city is the site of a controversial export terminal built by the multinational company Cargill to bring soybeans out of the Amazon. Near Santarém, we would be able to see it all: unblemished jungle, jungle being cut back, soy fields, and the terminal itself, a cruel agribusiness dagger thrust directly into the pulsing, green heart of the world. At least, this was my fervent hope.

With research outsourced to Adam, it fell to me to direct field operations. I put together a reporting plan.

1) Buy airline ticket (IMPORTANT).

2) Fly to Brazil.

3) Exit airplane.

4) Exit airport.

5) Find taxi.

6) Ask taxi driver to take us to the Amazon, preferably the part on fire.

This was a plan I could handle, especially once Adam–seeing I had no intention of addressing Action Item No. 1–went ahead and bought our plane tickets himself. (I still haven’t paid him back.)

Then, as if to punish me for it, he shows up in my office wearing a green visor and waving a sheaf of papers, and gets all NEWSFLASH on me. The Brazilian government had just announced record‑low rates of deforestation for 2010. The lowest rates of deforestation ever recorded.

Those bastards. Here I was, about to drag my ass to Brazil to go adventuring through a jungle‑clearing orgy of absolutely first‑rate proportions, and up pops President Lula to tell me that deforestation is more or less solved. It was disgusting. Since when? Wasn’t deforestation like death and taxes? I’d been hearing about the inexorable destruction of the rainforests since I was a child. Now that, too, would be taken away from me?

It didn’t matter. We had our tickets. And so we turned to the traveler’s customary scramble of last‑minute chores: suddenly you have a critical need for magnetic bug‑proof socks, and a polarized hat, and a million other little purchases to help you convince yourself that you actually want to go on the trip.

While Adam spent his last few evenings researching deforestation patterns and Brazilian environmental policy, I screwed around on the Internet, disconsolately hoping for something to spur my curiosity. Somehow, I stumbled across an advertisement for some real estate near Santarém:

For Sale: 1,907 acres (766 hectares) of prime forest land adjacent to the Tapajós National Forest in the Amazon region of Brazil.

Rainforest for sale? I called at once. Soon I was talking to a gravelly voice on the other end of the line. His name was Rick, and he lived in Michigan, where he ran a business importing high‑quality Amazonian wood.

“I own two thousand acres of what I consider the finest rainforest in the world,” he said. “I made a lot of money in the exotic lumber business. So I bought it because…well, ’cause I could do it, I guess. It would be a soy farm or a cattle ranch by now, otherwise.”

Since then, though, the economy had crashed, and business was bad. His company had shed most of its employees, and he couldn’t afford to keep his rainforest anymore. And even though he had made his fortune in wood, he wanted to find a buyer for his forest who wouldn’t just cut it down. Much of the land around it had already been converted to soy fields.

“I planned on making so much money in the business that I’d give my piece of forest to the state, or a college, or a nonprofit,” he said. But for the past few years it had been a struggle just to hang on to it.

I told him I was going to Santarém in a couple of days.

Man, he said, I wish I were going with you. I was thinking about going, but I guess it’s too late now. Have fun. You’re going to love it down there.

A breezy city of a quarter million people, Santarém occupies a broad corner of riverbank just where the Amazon meets the mighty tributary of the Tapajós. Rick was right–Santarém is nice. I was instantly glad that Adam and I had decided not to go nosing into lawless pockets of the countryside in search of illegal logging. We might have overcorrected with tourist‑friendly Santarém, but that was okay. I needed to relax, needed a vacation from the cold weather that had been creeping down onto New York, and from everything else.

We strolled out from our hotel in search of Gil, our fixer and translator. As we walked, we could see the meeting place of two massive rivers: on the far side, the muddy water of the Amazon, its opposite bank more than two miles away, and on the near side the Tapajós, famously dark and clear. Half a mile out from the bank, the two came together, mixing in a sinuous ribbon that looped downstream for miles.

Although Gil had come highly recommended, I was a little apprehensive about meeting him. The last few days had seen an erratic series of e‑mails culminating with an abrupt request for electronics. “Bring me a iPod touch 4G 32GB,” he wrote. “My girlfriend is pregnant if you bring me two i name our kid after you.” Our fixer had turned into an Internet scam from Moldova. Uncertain what to do, I had split the difference and purchased a single iPod. It was now in my backpack.

Gil’s place was an old yellow house just a few steps up from the waterfront. A windsurfing board lay on the sidewalk out front, and the house’s door‑like windows had been flung open to make a shallow terrace facing the river. Earsplitting rock music blared from inside. On tiptoe, I peered through a side window, looking for the mild‑mannered face we had seen in a photo on his website.

Instead, I saw a half‑naked wildman in surfing trunks, hunched over an old computer. I knocked. He didn’t hear. He was glaring at the screen with a ferocious intensity, baring his teeth as he pecked at the keyboard. I knocked again, louder this time, and he looked up with a start, a flourish of hair tumbling down his shoulders. He had seen us. I felt the urge to run, but he had already sprung to his feet and was charging at us, shouting over the music. He was offering us caipirinhas–Do you know what that is? It’s our national drink! Do you have them in New York? You do?! –and welcoming us to Santarém, and telling us how excited he was that we had come.

How to describe Gil Serique? He was a son of the rainforest, born in a speck of a village on the jungle bank of the Tapajós, a village without electricity or running water, accessible only by boat. “Paradise!” he called it. Now he was a multilingual river guide, a translator and fixer for visiting journalists, and above all, the prototypical Amazon beach bum. He wind‑surfed every day he could, launching into the river directly across the street from his house.

And he hustled. He had printed booklets to promote his guiding business, he cultivated contacts with the cruise ship operators who passed through Santarém, he obsessively updated his blog and his Facebook status (3,103 friends at last count). His house was a nexus for anyone interested in the rainforest, or its destruction, or in surfing, or in drinking, or in talking. He embarked at once on a series of absurd and exaggerated stories–about his neurosurgeon pilot friend who was descended from American Confederates, about having been in a Michael Jackson music video, about how, to his shame, he had once almost become an exotic‑species smuggler.

The iPod Touch, it turned out, was part of a scheme to supplement his guiding income. Accepting it as partial payment for his services, he told us that iPod Touches were rare in Santarém; he planned to sell it at a 100 percent markup. “I should have everyone pay me in iPod Touches,” he said. And then he told us some more about windsurfing. Always windsurfing. He was a man feasting on life like a crazed animal. If something was funny, or pleasant, or nice, then laughter was not enough. Instead his eyes would bug out, his teeth would flash, and he would emit a bloodcurdling scream. “AAAGGHH!! ” He was a man afflicted with joy.

There were beers in our hands and we were leaning against the terrace, watching the good citizens of Santarém stroll the waterfront. Gil was the luckiest guy in the world, he told us breathlessly. He didn’t know how he could be happier. He loved Santarém, loved the forest, loved his girlfriend, loved guiding, loved us. At forty‑six, he was about to become a father. He shared the crumbling four‑room house with his pregnant “bride‑to‑be.” She was seventeen–not much more than a third his age.

“I’ve got the best life here, really,” he told us, and then seemed to become overwhelmed by what he had just said. His eyes widened. “I love this town! I really love it! AAAGGHH! ”

The conversation turned to deforestation and soy. It was disorienting the way Gil, with a maniacal gleam in his eye, somehow made screaming and drinking and cogent conversation all work together. He talked about the Cargill terminal, about the patterns of deforestation in the region.

“The roads in the Amazon were all built in the seventies,” he said, his accent a reedy mix of Brazilian, British, and surfer. “Before that all the human pressure was along the waterway. With the roads, it’s gone into the land.”

The Amazon is a frontier forever under the sway of a new rush. Just the past hundred years have seen rubber booms, timber booms, gold rushes. Now soy and bauxite were taking the lead. But exploitation came in many forms. Even something as simple as boats with onboard refrigeration, which allowed fishermen to stay out longer, meant huge pressure on the fish in the river.

Would we like another beer?

In Gil’s view, though, the exploitation had a flip side. “I got a lot more interesting work once they started devastating the Amazon,” he said. “Normally, I’d be guiding nature lovers, but as Amazon conservation and everything gets bigger, I do more and more work with people like you, who want to see nature’s problems.” He was operating on the bleeding edge of ecotourism.

But cruise ships were his bread and butter. During the season, ships packed with hundreds of tourists made their way from the mouth of the river up to Manaus, stopping for the day in Santarém.

“Cruise ship industry, this is a beautiful industry,” Gil said. ’Cause they come here, they’re all old, and they’re loaded. But they’re cool–they’re really cool. Anyone who comes to the Amazon is cool.”

I had noticed a few tour‑boat tourists turning circles on the waterfront, binoculars in hand. Cruise boats can ruin a town; in Juneau, where my father lives, the entire downtown area has become overrun with cruise ship passengers and the insipid economies that spring up around them. But that hadn’t happened here yet.

Gil put down his beer. “I love whorehouses!” he cried.

I couldn’t quite remember how we had come to this part of the conversation, but here we were.

He became serious for a moment: “I mean, the way we treat women in this country is terrible. Really.” Then he brightened. “But still. There is this one whorehouse in Manaus…”

Was I supposed to nod? Oh, yeah…Whorehouses!

Our host went on, oblivious to our discomfort. He said you could get a girl for twenty reals–about ten dollars. Here was another form of exploitation in the Amazon, one Gil didn’t mind participating in.

A pair of young women crossed into the park, strolling arm in arm. Gil assured us that the girls who walked by his house were the most beautiful girls in the world. “You’re going to love the girls here,” he said. “They’re amazing.” Concerned that he would start making introductions, we hastened to let him know that we both had girlfriends. Somehow, even for me, this remained true. For reasons unclear, I still lived with the Doctor.

It was dark. The park had filled with young couples, and families, and bands of teenagers. Children tumbled through the playground. A soccer game scuffled on the basketball court. Gil had turned philosophical. He felt so lucky to be alive, he told us. His sense of gratitude was oddly specific, though. He was grateful, first, for his carbon fiber windsurfing board. This was an amazing piece of technology.

“My first board weighed a ton, but this one is only like ten or fifteen kilos,” he said. “I’m so grateful for that. And I’m so grateful that I’m forty‑six and can get lots of little blue pills that can give me an incredible erection.”

Adam choked on his beer.

“Not Viagra, man,” Gil continued. “Viagra will give you a big erection, but it will make it very wide, you know.” He gestured. “Very wide. But these little blue pills, I get them right around the corner. They cost like nothing. You take one of these pills, you will have a serious erection. You haven’t taken those pills?”

We confirmed that we had not.

“So those are the two things I’m so grateful for at this time, that I can have in my life,” he said.

“Carbon fiber and little blue pills,” I listed, by way of a recap.

“That’s right,” Gil said, holding two fingers up. His eyes widened with realization. “There’s not a third thing! AAAGGHH! ”

We took off. We had hardly rested since New York. “Don’t go!” Gil cried. But then he relented and walked us to our hotel, two blocks away. He had decided to go around the corner for a blue pill.

“I’m going to have some serious sex tonight,” he said. “Thank you for this wonderful day!”

Highway BR‑163 begins in Cuiabá, at the southern end of the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso, and runs north for more than a thousand miles, plunging directly through the Amazon. Built in the early 1970s, it is still mostly unpaved where it passes through the jungle, and during the rainy season it becomes a river of mud. Trucks founder in its legendary ruts and potholes, their progress slowed to less than a hundred miles a day. BR‑163, it would be fair to say, is one of the world’s crappiest major roads.

It has the distinction, however, of being one of only two roads that traverse the Amazon from north to south. As the Economist put it, BR‑163 joins “the ‘world’s breadbasket’ to the ‘world’s lungs.’” It links Mato Grosso–the agricultural powerhouse that has made Brazil the world’s second‑largest soy producer, after the United States–to the forested expanses of Pará. As such, the highway is a focus not only of commerce but also of some serious environmental anxiety. As Gil had pointed out to me, roads bring deforestation. You only cut down forests you can reach, and only turn jungles into ranches and farms if you have a way to carry off the beef and soy.

Once there is a road–even a crappy one–civilization begins to course along it, pushing out into the bordering forest. Humans like to think of themselves as builders and conquerors, but their presence spreads more like a vine, sending out tendrils, building a network, growing into the gaps until it forms a smothering blanket. Satellite images show that by the time it reaches the Tapajós River, BR‑163 is sprouting cleared land in dense, perpendicular gashes, each a dozen miles long, like the teeth of a giant rake.

The road terminates, finally, in Santarém, at the western end of the waterfront. And it is here, not a hundred yards from where BR‑163 runs out of places to go, that Cargill Incorporated of Minnetonka, Minnesota, built its soy terminal.

The terminal is Santarém’s most conspicuous structure, a metal barn that stretches several hundred feet, with a huge Cargill logo on one side. A grain conveyor more than a thousand feet long extends from the northern end of the building to a tanker dock in the river. On the day we cruised past it, on a riverboat rented from a friend of Gil’s, we saw a bulk carrier receiving its cargo, beans pouring out of massive downspouts, and plumes of soy dust floating out of the ship’s compartments. Docked at the next moorage upriver was a Holland America cruise ship, a little smaller than the soy ship, and blinding with its bright wall of cabins. Next in line, smaller still, was a timber transport waiting for the cruise ship to vacate the dock so it could resume loading containers of wood. At a single glance, we could see the comings and goings of three major Amazonian industries: soy, tourists, and timber.

Construction of the Santarém terminal began in 1999 and was finished in 2003, even though Cargill had failed to do the necessary environmental impact study–a fact that resulted in the terminal being declared illegal by the Brazilian courts multiple times. Nevertheless, it opened.

For Cargill–the largest privately held corporation in the United States–building the terminal was a strategic move that allowed soybeans to get to market faster and more cheaply than before. Soy from Mato Grosso could be shipped north by river or trucked along BR‑163. At the Santarém terminal, the soy could then be offloaded and stored before being shipped directly to Europe via the Amazon River. The fact of the terminal would therefore be a further incentive for the Brazilian government to pave the rest of BR‑163. And that would mean yet another launching pad for assaults on the rainforest. (Paving a thousand‑mile‑long highway through the jungle, though, is easier said than done. As of 2012, it is still unfinished.)

There was incentive, too, for any farmer in Mato Grosso who cared to do the math. Why bother sending only your crop to the Cargill terminal when you could send the entire farm? Land was cheap around Santarém, and a soy farm built close to the Cargill terminal would save on both land and transportation costs.

Farmers flooded north. By 2004, a year after the terminal opened, cultivation of soy in the area had jumped to 35,000 hectares (about 85,000 acres, and a five‑year increase of more than 2,000 percent) and land prices had shot up by a factor of thirty. Local farmers were under ever‑increasing pressure to sell their land to the soy farmers. Soon, soy was being touted as rainforest enemy number one, and Greenpeace activists were crawling over the Cargill terminal building–in much the same way as they had crawled over the machinery of the oil sands mines–and demonstrators in the UK were showing up at McDonald’s dressed as chickens to protest the use of Brazilian soy as chicken feed. The soy rush was on.

The highway in the dark. BR‑163. The kilometers ticked by. This close to Santarém, the road was paved and free of potholes. Our driver sped south with abandon. He was a cheery, hulking man whose nickname translated as “Mango.”

Locations on the road south of Santarém are found not by signs or named roads but by their kilometer number. We were headed for a turnoff somewhere in the low 70s. There, we would meet some people who spent their days ripping trees out of the rainforest. It was all perfectly legal, though–part of a sustainable logging project, and nothing to get upset about, unfortunately.

Dawn brightened by increments behind the tinted windows of Mango’s car. We saw where we were. The rainforest. Right! After a couple of days in Santarém, a morose foreigner could almost forget that he had come here to see the jungle, to walk around inside the vast hydrological pump that is the Amazon, which lifts and distributes an ocean’s worth of water across the Americas, shaping and driving weather patterns around the continent. Now, the Amazon canopy flew past, mist rising among the treetops. On the right, at the boundary of the Tapajós National Forest, trees approached to the edge of the road. Gil squinted through his window, looking for kilometer markers. On the left, the vista modulated between forest and rangeland–and then would fall away into the flat blankness of a soy field: mile‑long rectangles of bare earth, stretching away to a residual wall of forest in the distance.

We reached the logging camp at around seven in the morning. The loggers were meeting in a bare, wooden room in the main building. Men and women in hard hats and work clothes stood in a circle and made announcements. There was laughter and applause. They joined hands and said a prayer. Then we went out and got into the back of a large, covered truck and bounced and shuddered down a rutted dirt road in the direction of the Tapajós River, into the heart of the national forest. We were riding with the Ambé project.

The idea of logging in a protected forest is probably abhorrent to most people, at least those who aren’t loggers. After all, what’s protected supposed to mean? Here in the Tapajós, though, a collective of people who live on the margin of the forest have been allowed a “sustainable” logging concession. The idea is that this will offer them alternatives to slash‑and‑burn agriculture and illegal logging, and provide economic development and improve living standards in the community without severely degrading the forest.

The key is that the people making money off the forest are the ones who call it home. Once they are living off it, they become critical stakeholders in its preservation; the community can only be sustained by the forest so long as the forest continues to exist. Suddenly it isn’t just a few napping forest wardens who stand between the jungle and an army of illegal loggers and rule‑bending soy farmers. The forces of not in my backyard are hitched to the cause of preservation.

The air changed as we entered the forest, becoming suddenly rich and earthy, the heat of the day eased by moisture and shade. The truck dropped us off and drove away, leaving us to follow a small survey crew on its morning rounds. I listened to the jungle: squeaks and whoops, squawks and trills, sounds that must have been coming from a bird or an insect but that sounded like someone blowing across the mouth of a bottle. Cascades of insect noise, almost electronic. Calls and responses. Sounds that were weirdly familiar–that I had heard before in movies and museum exhibits. The soundscape makes the jungle.

The survey crew went about its work. I tagged along behind a cheerful man with a machete, doing my best to stay out of the swinging whirlwind of his blade.

I wondered why I was sweating so much. In the deep shade of the canopy, it wasn’t even hot–yet I sweated. Never in my life, not even in moments of optimal gym‑nirvana, had I sweated like this. My shirt was soaked. My hair was soaked. My arms were soaked. I could not have been more drenched by a sudden downpour. The very hard hat on my sweating head was itself sweating. Moisture dripped from its brim. How? The question asked itself. How does a plastic hard hat sweat?

A needle of pain in my thigh. I looked down to see a green dagger sticking out of my leg. Its spiny brothers pointed at me from nearby branches. I pulled it out, a two‑inch thorn. The air’s suffusing odor of loamy decomposition suddenly took on new significance. It was the smell of the jungle breaking down and digesting anything that didn’t keep moving. The Amazon wasn’t just a lung. It was a stomach.

The morning survey done, we came back to the service road and walked along it for a while, toward a meeting point where the truck would pick us up. Every curve revealed a narrow vista–another towering queen of a tree, wearing a leafy corona over an impossibly slender trunk. A patch of brilliant indigo half the size of my palm materialized in the air: a butterfly. Adam crouched over a snail at the edge of the woods. In the middle of the road, a thin cable of succulent green hung out of the sky. I held it, felt the elastic connection between my hand and the distant canopy–and then gave it a tug. It broke, length after length of vine spooling down on my shoulders.

Gil was everywhere with the iPod Touch. Instead of selling it, he had fallen in love with the thing and had decided to keep it for himself. Now he roamed back and forth, taking videos.

Gil had a special connection to this place. His grandfather’s family had lived here once, before it was a protected forest. They had made a settlement of their own, with about a dozen family members living off a piece of land that Gil’s grandfather considered particularly rich. In the early 1970s, though, the government had decided to protect the area by creating the Tapajós National Forest, and had expelled many of the people who lived there. Gil’s grandfather had been forced to sell his land.

“It was a reasonable amount of money,” Gil told me. But it had been disastrous for the family. Instead of farming together, they found themselves looking for new and unfamiliar jobs. “Like truck driver, gold prospector, fisherman,” Gil said. One uncle had opened a brothel and eventually sank into drug trafficking and violence.

Gil didn’t think that creating the national forest had been wrong–only that it had been created on the wrong model. “See, in those years, the policy was based in the USA’s Yellowstone,” he told me.

He couldn’t have chosen a more relevant example. Yellowstone was the first national park in the world, and its creation, in 1872, marked the moment in which white Americans truly fell in love with the splendor of the land they had conquered. But for that love to grow, the ideal of wilderness as a source of rapture and recreation had to be separated out from the loathing we all felt for native Americans, whose presence in the West tended to distract from our John Muir‑style reveries.

Muir himself, the St. Francis of the American West and a prophet of wilderness preservation, admitted that he was barely tolerant of the native Americans he encountered. In 1869, he wrote that he would “prefer the society of squirrels and woodchucks.” Muir’s reverence for what he saw as the natural order of things continues to fuel conservation today, but it didn’t extend so far as to include humans–of any color–as part of the environment. “Most Indians I have seen are not a whit more natural in their lives than we civilized whites,” he wrote. “The worst thing about them is their uncleanliness. Nothing truly wild is unclean.”

Native Americans were excluded from Yellowstone at its creation. Though people had been present in the area that was to become the park for thousands of years, native American practices of hunting and planned burning were anathema to a view of nature as sacrosanct from human involvement. If native Americans had been allowed to remain, they would have gotten in the way of all the nature white people wanted to appreciate. The creation of Yellowstone formalized the idea that human beings have no place in a protected wilderness–unless they are tourists.

As a result, some of the places we consider most pristine, most wild, are in some ways deeply artificial. A popular park like Yellowstone is probably more controlled, more managed, than the Exclusion Zone of Chernobyl. And even parks less besieged by visitors than Yellowstone or Yosemite are premised on ideas and laws that define human beings as outside of nature.

This artificial division between natural and unnatural pervades our understanding of the world. Industrialists may hope to dominate nature, and environmentalists to protect it–but both camps depend on the same dualism, on a conception of nature as something to which humanity has no fundamental link, and in which we have no inherent place. And it’s a harmful dualism, even if it takes the form of veneration. It keeps us from embracing a robust, engaged environmentalism that is based on something more than gauzy, prelapsarian yearnings.

But we cling to the ideal of a separate and perfect nature as though to give it up would be the same as paving over the Garden of Eden. When I met with the writer and academic Paul Wapner, whose ideas I’m stealing here, he told me that a colleague had warned him not to publish his book on this subject, titled Living Through the End of Nature. His colleague thought it was a bad career move, and that anyone who argued that the concept of nature was no longer a useful one was giving away the farm.

The farm has already been given away. We’re just so entranced by the concept of nature‑as‑purity that we won’t face facts. Our environment is not on the brink of something. It is over the brink–over several brinks–and has been for some time. It was more than twenty years ago that Bill McKibben pointed out the simple fact that there is no longer any nook or cranny of the globe untouched by human effects. It’s time to stop pretending otherwise, to stop pretending that we haven’t already entered the Anthropocene, a new geological age marked by massive species loss (already achieved) and climate change (in progress).

But the dream of nature is so dear to us that to wake from it seems like a betrayal. The sense that we have not yet gone over that brink–not quite–is what motivates us to our ablutions, our donations, our recycling, our hope. But it is a great untruth. The task now, perhaps, is not to preserve the fantasy of a separate and pure nature, but to see how thoroughly we are part of the new nature that still lives. Only then can we preserve it, and us.

We went to find the rest of the loggers. The truck dropped us at the edge of a large, muddy clearing with a dozen large, felled trees stacked around its periphery. The air was alive with the riot of engines and saws. The clearing was a temporary holding area for trees that had been felled in the surrounding forest. A man with a chainsaw went from log to log, sawing off the sloping protrusions of roots at their bases, while other workers, both men and women, measured and marked them. An angry, saber‑toothed forklift picked logs up in twos or threes and dropped them into a pile. They landed with a deep thunk.

After our peaceful stroll through the forest, the racket was overwhelming. To be honest, I think we were a little freaked out by how industrial it all was. I had expected a sustainable logging collective to involve a dozen nice folks and a good chainsaw. Instead, the nice folks had serious machinery and meant business. You could have taken pictures here that looked like every preservationist’s nightmare–a mayhem of logs and mud. Or you could have taken pictures of the jolly, hardworking crew, and of the communities they supported, and of the forest that, it was hoped, their logging was helping to protect.

“The skidder is coming!” Gil said. “You can’t see this very often! Let’s go, let’s go!”

We ran to the edge of the clearing and into the forest. A corridor of crushed vegetation led deeper into the jungle. Something had been through here. Trees were scraped and bruised where it had passed.

From the forest, we heard the shriek and growl of an engine. It heaved into sight: the skidder. This was how logs were brought out from the inaccessible interior, where they had been felled. They were dragged out behind this narrow, streamlined tank, a low, blunt‑nosed hedgehog of a machine that was now headed our way.

Gil raised his iPod to record it. “We want to make sure not to be near it when it passes,” he said, in the staring voice of the awestruck. The skidder plunged toward us, a colonizing robot from another world, surprisingly fast, shouldering trees aside as it bore closer, nearly on top of us.

And then we were running for our lives, screaming with joy and terror, leaping out of the way. It passed just a few yards from us, wheels grinding, and then it was gone. In its wake, a gigantic log slid coolly, massively, over the forest floor.

“Fucking shit! ” Gil screamed. He was waving the iPod in the air. “It wasn’t recording!” His disappointment took the form of an intense, quivering joy. Then we turned, and the machine was there again, back from the clearing, outbound for another log, bullheaded, inhuman, implacable.

On our way out, we stopped at the patio –the storage area near the highway, where logs awaited transport. They were piled twenty or more to a stack, each log three feet in diameter. We drove over soft ground flooded with rainwater, winding our way through a dozen stacks, two dozen. Flying ants wavered against the mountainous piles of logs. The purple stylus of a dragonfly appeared and disappeared. The air was thick with wood and rot.

Gil shook his head. “It’s hard to believe this won’t fuck up the forest, isn’t it?”

Gil met us for breakfast at the hotel. As we planned our day over coffee and pastries, a muscular, middle‑aged American man approached our table and started talking windsurfing with Gil. The American was wearing flip‑flops and shorts, and had long, curly gray‑blond hair and a deep, gravelly voice. A surfing buddy of Gil’s, I thought. The subculture of Amazonian beach bums–one that I hadn’t known existed two days earlier–was growing every day.

Then he turned to me, a business card in his hand. It was Rick. The man from Michigan who owned his own rainforest. On two days’ notice, he had decided to come down to meet us in Brazil. He said there were a lot of misconceptions out there about the Amazon and about logging, and evidently he thought my presence in Santarém was a once‑in‑a‑lifetime opportunity to get his story out.

I don’t know what I had expected Rick to look like–a doughy guy in a polo shirt and khakis?–but it wasn’t this. With his stony features and huge arms, he looked like a muscle‑bound Gary Sinise. Or like someone who might choose to beat the crap out of the real Gary Sinise. He was accompanied by one of his few remaining local employees, a smart, understated young man whom Rick called Tang. They got some coffee and breakfast and joined us at our table.

Rick lived wood. His company imported wood to the United States, processed it, and sold it as exotic flooring. The business had been driven by the cheap money of the housing bubble, he said. “People building ten‑thousand‑square‑foot houses because they could, putting in exotic hardwood floors because they could.”

He got down to the business of misconception‑correcting. “On TV in America, they used to show some burnt, dying wasteland, and they’d have a logging truck driving through it,” he said. “The assumption is that loggers cleared it. That they just nuke the place. But that’s not the case.”

Of all the trees growing in the rainforest, Rick told us, only five or six species were commercially viable. So logging in the Amazon had always been extremely selective. “If there were no cattle ranching, and no soy, the average person wouldn’t be able to tell that one single log had been cut around here. Because there’s no market for 94 percent of the forest.”

Rick knew, though, that it was more complicated than that. “The worst thing loggers do is make roads,” he admitted. And that created access for commercial agriculture. We later spoke to one of Rick’s colleagues on this point. “Loggers don’t destroy the forest, but they open the door,” he said. “We are like high‑class gangsters. We come into a museum, but we only steal the one multimillion‑dollar painting. Then we leave the door open, and everyone else comes in after us, and they take everything. Even the lightbulbs.”

Rick’s problem wasn’t with the fact of logging, but with how it was done. He couldn’t abide waste. Huge amounts of wood had been wasted to achieve economies of scale. “It was so cheap here for perfect logs. It was the same in Michigan a hundred years ago. You’d lose money if you touched anything but the filet,” he said, referring to the large, straight section at the bottom of the tree. The rest of the tree, from the lowest branch on up, was left to rot. “Billions and billions of board feet get wasted. I could build entire industries off the waste here, if I could just get access. It drives me crazy. I’ve been trying for years to see if I could get ahold of the tops left over by loggers–just their leftovers. And you can’t do it. It just rots. There are so many rules, it’s…” He grabbed his head. “It’s Brazil.” Sometimes entire forests were wasted. He had once visited a large bauxite mine nearby. Bauxite, the ore from which aluminum is derived, is big business now in the Amazon, and multinational companies cut down large tracts of forest to begin their open‑pit mines.

“They had these piles of logs,” Rick said. “They were prepping to bury them. It reminded me of pictures from Auschwitz. And can you get those logs? No.”

He was so passionate about waste that he had started a Brazilian subsidiary based on it. The concept was to take leftover sawmill logs and use them to custom‑build timber‑frame houses, turning scrap into a luxury product. Rick nodded his head toward Tang, who had grown up nearby. “He’s been building boats since he was three years old. He’s one of the best timber framers in the world,” he said. “So the idea was to use all that local talent that’s here, and then use some resources that are being wasted. Not just turn the forest into a commodity.”

He had called his local company Zero Impact Brazil. The lumberman was trying to turn over a new leaf. He admitted, though, that he had made most of his money on the commodity side: “For a while there, I was the largest buyer of forest products in Santarém.”

Now that was all over. The housing boom had crashed, and the market for exotic flooring had gone with it. The entire timber industry had died back. Tang told us that over the last five years, two‑thirds of the sawmills in the area had closed. Logging trucks had gotten scarce.

I stared into my coffee cup. Let this be a lesson to you, I thought. Never wait to see a rainforest being logged out of existence, because one day you’ll wake up and it will be too late.

“Yeah,” Rick said. “Lots of money got dumped in here from all over the world. Big investments. They come here with real big eyes.” And like so many others, they had gotten burned. “The typical business model in the Amazon,” he said, “is you go there with a lot of money–and you leave broke.”

Now it was Rick’s turn. The timber frames weren’t selling. Zero Impact Brazil was surviving only by selling off its assets.

We stood up to go, agreeing to talk again soon, to arrange a visit to Rick’s rainforest. We’d go down there and “goof around,” he said. He was insistent on that point–on the goofing around. Adam and I exchanged a glance. What did that mean, exactly?

Rick also wanted to talk some more about the forest, about waste, about his company. “I wanna portray us as at least the guys who have got good intentions,” he said.

Stoking a mild despondency about Brazil’s failure to keep up its end of the environmental‑horror‑story bargain, I turned for succor to the Catholic Church. Adam had uncovered an activist priest who promised to say inflammatory and pessimistic things about the Amazonian situation. He had made headlines overseas–the BBC called him “the Amazon’s most ardent protector”–and had a reputation as a fierce champion of the rainforest.

Gil knew where to find him, of course. He knew everybody, perhaps because he spent his every spare moment on the tiny terrace of his house, greeting passersby, waving, hollering, gossiping. Walking around Santarém with him was like tagging along for a victory lap with a popular former mayor. Acquaintances and friends shouted from windows and sidewalks on every block.

We went looking for Father Edilberto Sena not at his church but at the offices of his radio station, which says something about his approach to liberation theology. The station operated from a small, two‑story building on a busy street up the hill from the river, and Sena used it to promote his activist causes, beginning with an editorial broadcast every morning.

From half a block away, Gil spotted him pulling into a parking spot, and we introduced ourselves on the sidewalk. He was a short man, youthfully sixtysomething, with a pugnacious smile and good English.

As we walked toward the entrance of the radio station, two young women crossed our path. Sena stopped in his tracks and turned to us.

“One problem of the Amazon…” he said. “Too many beautiful girls around.”

Smiling, he laid a hand on his chest.

“A poor priest suffers. ”

From a media relations point of view, this seemed like a questionable way for a priest to start in with a pair of visiting journalists. But it was part and parcel of Father Sena’s rebel persona, which he clearly held very dear. In his office, I asked him what he thought about the Brazilian government’s figures, which showed that deforestation had reached record lows.

“Bullshit!” he cried, his face shining. He acknowledged that deforestation had diminished in 2010, but insisted that this wasn’t the whole story. “When you put it together with the deforestation of 2008, 2007…” He chopped his hand against the desk. “For the last eight years, we have a sum of 16 percent of the Amazonian forest destroyed.”

I was feeling better already.

Unfortunately, his figures were badly exaggerated. It had taken more like thirty years, not just eight, to destroy 16 percent of the Amazon. But that was beside the point. Deforestation was only part of the story, he said. “We ask, ‘Why are you, Mr. Government, continuing with huge projects of hydroelectrics in Amazonia?’ Government has a plan to build thirty‑eight hydroelectrics in Amazonia.” There were even dams planned for the Tapajós. “I feel the contradiction from the government,” he said. “Saying they are fighting to stop deforestation, and at the same time they are planning to build hydroelectrics that will destroy rivers, forests, and the people.”

Sena had brought the same defiant spirit to the fight against soy farming in the area. The organization he founded, called the Amazon Defense Front, had partnered with Greenpeace to protest the Cargill terminal. But the collaboration didn’t last.

“Greenpeace was a very important ally from 2004 to 2006,” he said. “Then we stopped…Our styles were different. We went to the street, to make protest. Greenpeace went jumping on the roof of Cargill.” He laughed. “And filming, and showing to Europe and to the world that Greenpeace was here!”

There were philosophical differences, too. “I am not an environmentalist!” he said, waving his finger in the air. “I am an Amazonianist. Because the Amazon is more than the environment. It is also the people.”

He smiled the smile of a firebrand. “Greenpeace has money. But it doesn’t help much when you don’t have a holistic viewpoint. They defend the forest. They defend the animals. They forget that the environment includes the people that live here. That’s the difference. We defend our people.”

It was the Ambé approach, applied to environmental politics. Without taking people into account–in your activism, in your national parks–something essential was missing. And Sena didn’t just mean indigenous people. He also included the small farmers who had been displaced by soy, and more than twenty million other people spread across the Amazon basin, whether in the countryside or in big cities like Manaus. They were all critical stakeholders.

But there was at least one group that didn’t count.

“Before 2000, we didn’t know the plant of soy,” Sena told us. But by 2001, soy farmers from Mato Grosso had started showing up. “They went with money and bought this land,” he said emphatically. “They didn’t come to live here. They came to cultivate here.”

Newly arrived from the south, the soy farmers had not integrated well, not least because their mechanized farms offered few jobs for the people of Pará. The locals took to calling the soy farmers soyeros, a play on the Portuguese word for dirty.

“Soyeros don’t like it when we call them that,” Father Sena said. “But they are dirty. They didn’t come here to join us, but just to suck the possibilities of this land.”

Call it the Sena Doctrine. People are an indispensable part of the environment–unless they’re dirty bastards.

We trundled down BR‑163 in Mango’s car again, to about kilometer 45, where we met Nestor, a small‑time farmer who had survived the soy fever and kept his farm. Nestor sold us beers and, together with his son, took us on a walking tour of his manioc fields. “There were many people living here who owned small farms,” he said. But in the first five years of the decade, buyers from the south had swarmed in, bidding up land prices. Most people had taken the money. “They sold the land, and the tractors came and finished with it all.” A nearby village called Paca had been wiped completely off the map to make way for soybeans. Even the Pentecostal church in the village had sold out and moved. “They sold it all,” said Nestor’s son, laughing. “They brought down the church to plant soybeans. You can’t even tell there was a church there.”

Nestor blamed the local politicians who he said had brought Cargill in: “The government brought these people to bring progress. And maybe it did. But it also brought bad things…People saw the money and thought it would never end. One person would sell, and that would inspire the next person to do the same.”

It sounded like a frenzy, I said. Gil translated, using the word locura, for “madness.” Nestor and his son nodded vigorously. “Era,” they said. It was. Along this stretch of highway, Nestor told us, only he and his brother had kept their plots of land intact. Everyone else had sold at least part.

The frenzy had changed the local environment, in ways both subtle and obvious. We met multiple farmers who complained about the chemicals that neighboring soy farms used on their crop, and about how the soy monoculture had increased the burden of pests on small farms nearby. “There are a lot of diseases in their fields,” one man said of the soy farmers. “I plant rice and I get nothing. If I plant beans, the insects eat it all. We can’t harvest anything.” He claimed that the soy farmers were able to thrive only because of all the fertilizers they used.

He said, too, that such large, open tracts of land changed the winds and the temperature around them, and that the simple absence of shade made life harder. Where once they had walked great distances in a day’s work, the wide expanses of the soy farms meant less protection from the punishing Brazilian sun–and thus less walking.

We asked Nestor why he hadn’t sold. Buyers had been offering big money. He said that wasn’t important. He didn’t like money.

“If you don’t like money,” I said, “then we won’t bother paying for the beers.”

He laughed. “We like a little money.”

Now the ones who had sold their land and moved to Santarém regretted it, he said. They wanted to come back. Another small farmer down the road told us the same. “Many think that when they move to town, the money they got will never run out,” he said. “They go to town, buy a house, a TV set, a refrigerator. But they never got an education, so they can’t get a job. When the money runs out and they have no means to work, they regret selling the land.”

We never stopped hearing about the families who regretted selling–from Nestor, from other farmers, from Father Sena. Here, people worried less about soy’s effects on the forest than about its effects on their society, about the ways it had impoverished the people who had sold their farms.

“Now they are after a small plot of land and can’t find one,” Nestor said. “Their daughters became prostitutes. Their sons became glue‑sniffers.”

Gil said it was the same as when his grandfather had been bought out of his home in the Tapajós National Forest. “They ran out of money right away. It happened to most of my uncles.”

Another interesting thing about Nestor was that his farm was on fire.

Much of our conversation took place in the middle of a smoldering field, similar to the one in which I would later melt the soles of my boots, staring at those ghostly, tree‑shaped piles of ash. The fire was the reason we had stopped to talk to Nestor in the first place. I was here to see some deforestation, dammit, and if a field of slashed‑and‑burning trees wasn’t deforestation, then I didn’t know what deforestation was.

Turns out I didn’t. In the Amazon, deforestation is a dispiritingly messy subject to unpack. Even Adam found the topic surprisingly opaque once he got down to the nitty‑gritty of it for me. The main theme of any in‑depth article about deforestation in Brazil, he once told me, ought to be how frustrating it is just trying to figure out what counts.

Take Nestor’s case. You would think a charred stump is a charred stump, but not so. Nestor was just rotating his crops. Slash and burn has a scary ring to it, but around here slashing and burning is often part of a farmer’s yearly routine. The piece of land Nestor was burning had already been cultivated multiple times. He would grow a crop of manioc–a root vegetable known elsewhere as cassava or yuca–and then leave the field to become overgrown with trees and brush while it lay fallow.

Now, several years later, he was going to cultivate it again. To prepare it, he had cut down the new growth, let it dry for a few weeks, and was burning it off. From a carbon point of view, his footprint was neutral: the CO2 going into the air on the day we visited was CO2 that had been sucked out of the air by this vegetation over the course of the past five years or so. True, there was a carbon debt–and habitat loss–from the original establishment of his farm, but that had been decades ago.

The real argument is over what drives new deforestation. And it’s not as simple as who’s holding the chainsaw. A person cutting down trees might be there because of government incentives to encourage the settlement of “undeveloped” areas. A soy farmer may only have come north because land was too expensive in his home state–or because an American buyer like Cargill has set up shop in Pará. All sorts of things can prompt deforestation at a distance. A soy farmer using previously cultivated land could argue that he isn’t destroying the Amazon. But what if the small farmer who sold him that land goes off to clear new land somewhere else? To whom do you attribute the destruction?

Even if you can answer that question, you are then confronted with the situation that once an area of rainforest is settled, the settlers themselves become the de facto caretakers of whatever is left. Landowners in Brazil are subject to a unique forest law that obligates them to leave 80 percent of their land in native forest. Even giant soy farms aren’t allowed to clear more than 20 percent of their land. (The farming lobby is trying to change this law.) If the law were effective, it would mean that anyone who cut down twenty hectares of jungle would end up being responsible for protecting another eighty.

It’s hard to imagine a muddier picture. Decades ago, when Nestor first set up his farm, he might accurately have been characterized as the face of deforestation–sucking the possibilities of the land, as Father Sena would say. But now Nestor was a local stakeholder whose livelihood as a farmer depended on resisting the waves of development that followed him. His permanence on the land had earned him a place under the Sena Doctrine. But wouldn’t that happen to anyone who stayed long enough?

Come back in thirty years. Maybe there will be a proud soyero making a stand, refusing to sell his farm for the construction of a mega‑mall next to the Tapajós National Forest, and we’ll call him a defender of the Amazon.

“I don’t know what you do around here after dark,” Rick said. “I don’t drink. I guess if you drink, if you like to party, you can go to a bar and visit with people.”

Adam and I had bumped into him in the park across from our hotel and invited him to eat dinner with us. At an outdoor restaurant across from the waterfront, we sat on plastic patio furniture and ate steak and chicken, and Rick pressed on us once again the need to visit his forest. “We can swim, we can goof around,” he said.

Rick had first come to Brazil twenty‑five years earlier, seized by the idea of importing wood directly from Brazilian suppliers. In an era before e‑mail or widespread fax machines, finding those suppliers had meant coming down in person. So that’s what he did, wandering from city to city through the Amazon, knocking on sawmill doors, even though he spoke no Portuguese. (Twenty‑five years later, he still didn’t.)

It hadn’t taken long for the sawmill operators to figure out that, although he “looked like a hippie,” as he put it, Rick wasn’t there to protest, or to chain himself to a tree. He wanted to buy trees.

It made him his fortune. He became a major exporter of wood from Santarém. He told us that for several years in the 1990s, he was the biggest customer of Cemex–at the time, the largest logging company in Santarém. The world’s appetite for exotic lumber had been one of the forces sending tendrils of destruction into the rainforest, and Rick had cut out the middlemen, and fed it.

Yet he seemed less a businessman than a searcher of some kind. Whether it was the experience of seeing his business die back, or something else, he had been humbled.

He showed us a photograph of the river on his phone. Underneath the distant sliver of a kitesurfing kite, a tiny figure rode the surface of the water.

“That’s me,” he said.

He put his phone away. “You know how some people say that when you’re surfing, you connect with the water, or whatever?” he asked. “I can kind of relate to that now. When you’re kitesurfing, you’re really in touch with the environment. You’ve got the water, and the waves, and also the wind. You finally relax, and stop trying to control it. You stop fearing it.”

He laughed at himself. He was a gruff chisel of a man. Adam and I sat and listened. Over our shoulders, the Amazon and the Tapajós mixed and flowed, invisible in the dark.

“I don’t know what you’d call that,” Rick said. “Something like a religious experience.”

We went to find the soyeros, those dirty bastards from the south.

“I found out land was cheap in Pará,” said Luiz. “It was the only place I could afford it. So we came here to buy a plot of land and own it. That’s why we’re here.”

Luiz was a short man in his early sixties, with watery eyes and an uncertain gait. He was a soy farmer, with three hundred hectares under the plow, just up the highway from Nestor’s land. He was also, to my eye, drunk.

“Would you have moved here if the Cargill port wasn’t here?” Adam asked.

Luiz frowned and shook his head as Gil translated. “What would I do here?” He had come for the same reason as the other soy farmers. He had realized that while the price of soy would be the same in Pará as in Mato Grosso, the cost of transport would be much less.

“We only came here because of Cargill,” he said. “Not that Cargill went to Mato Grosso and called us. But we watch the news.”

We walked along the edge of his field, deep and crumbly with muddy earth, to the barn where he kept his combine. Luiz plunged his forearm into a sack of grain and pulled out a handful of dry soybeans, his balance wavering as he held it up for us to see. “Soybeans are dollars,” he said.

Luiz could see me staring at the combine, a tall, old machine with green sides. He swung up the ladder to the driver’s perch, and soon the machine rumbled to life, its rows of harvesting blades gnashing and turning. He turned it off and I climbed up to the steering wheel. I peered out at the soy field in front of me, and imagined rumbling through it on the combine at harvest time.

Things hadn’t worked out perfectly for the soyeros. The value of Luiz’s land had crashed by 60 percent since he’d bought it. Even worse, when he’d bought it, he hadn’t known he wouldn’t be able to clear off all the trees.

“The environmentalists ” He spat the word. Ambientalistas. “They came with these laws, and it was forbidden to clear more than 20 percent of the area.” He had been forced to lease additional land in order to grow a large‑enough crop. It made no sense to him. This was rich, flat land. It ought to be cultivated. And the forest on his land wasn’t even virgin forest, he said. There were no good hardwoods left on it, no monkeys, no fruit. The law ought to be that if you’re going to protect a forest, it’s a real forest.

But that wasn’t how it worked. “For the environmentalists, the farmers of Pará are criminals, some sort of thug,” he said, and laughed. “They’d be more hurt to see a smashed tree than a dead farmer.”

It wasn’t just the environmentalists either. Although religious, Luiz had stopped going to church. “I stopped going because I would feel angry,” he said. He knew what people like Father Sena called him. He just didn’t understand why. “The priests attack us, but we’re not criminals. We’re not harming anyone’s lives.”

We left. In the car, speeding back toward Santarém, Mango laughed. He couldn’t believe Luiz hadn’t known why people hated the soyeros around here.

I’ll tell you why they hate you, Mango said. It’s because you’re cutting down the forest, you asshole!

First there is a toucan on a branch, minding its business. The sound of synthesizers. Then a magnificent tree, r

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-05-08; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 1212;