General Characteristics

The noun is the central lexical unit of language. It is the main nominative unit of speech. As any other part of speech, the noun can be characterised by three criteria: semantic (the meaning), morphological (the form and grammatical categories) and syntactical (functions, distribution).

Semantic features of the noun. The noun possesses the grammatical meaning of thingness, substantiality. According to different principles of classification nouns fall into several subclasses:

1. According to the type of nomination they may be proper and commonNouns which name specific people or places are known as proper nouns(John, London). Many names consist of more than one word (John Wesley, Queen Mary). Proper nouns may also refer to times or to dates in the calendar: January, February, Thanksgiving. All other nouns are common nouns. Since proper nouns usually refer to something or someone unique, they do not normally take plurals. However, they may do so, especially when number is being specifically referred to: there are three Davids in my class.

For the same reason, names of people and places are not normally preceded by determiners the or a/an, though they can be in certain circumstances: it's nothing like the America I remember; my brother is an Einstein at maths.

2. According to the form of existence they may be animateand inanimate. Animate nouns in their turn fall into human and non-human.

3. According to their quantitative structure nouns can be countable (count)and uncountable (non-count).Common nouns are either count or non-count. Count nouns can be "counted": one pen, two pens, three pens, four pens... Non-count nouns, on the other hand, cannot be counted in this way: one software, *two softwares, *three softwares, *four softwares... From the point of view of grammar, this means that count nouns have singular as well as plural forms, whereas non-count nouns have only a singular form. It also means that non-count nouns do not take a/an before them. In general, non-count nouns are considered to refer to indivisible wholes. For this reason, they are sometimes called mass nouns.

Some common nouns may be either count or non-count, depending on the kind of reference they have. For example, in I made a cake, cake is a count noun, and the a before it indicates singular number. However, in I like cake, the reference is less specific. It refers to "cake in general", and so cake is non-count in this sentence.

This set of subclasses cannot be put together into one table because of the different principles of classification.

Morphologicalfeatures of the noun. In accordance with the morphological structure of the stems all nouns can be classified into: simple, derived (stem + affix, affix + stem – thingness); compound (stem+ stem – armchair ) and composite (the Hague). The noun has morphological categories of number and case. Some scholars admit the existence of the category of gender.

Syntacticfeatures of the noun. The noun can be used in the sentence in all syntacticfunctions but predicate. Speaking about noun combinability, we can say that it can go into right-hand and left-hand connections with practically all parts of speech. That is why practically all parts of speech but the verb can act as noun determiners. However, the most common noun determiners are considered to be articles, pronouns, numerals, adjectives and nouns themselves in the common and genitive case.

The category of number

The grammatical category of number is the linguistic representation of the objective category of quantity. The number category is realized through the opposition of two form-classes: the plural form :: the singular form. The category of number in English is restricted in its realization because of the dependent implicit grammatical meaning of countableness/uncountableness. The number category is realized only within subclass of countable nouns.

The grammatical meaning of number may not coincide with the notional quantity: the noun in the singular does not necessarily denote one object while the plural form may be used to denote one object consisting of several parts.

The singular form may denote:

a) oneness (individual separate object – a cat);

b) generalization (the meaning of the whole class – The cat is a domestic animal);

c) indiscreteness (wholeness or uncountableness - money, milk).

The plural form may denote:

a) the existence of several objects (cats);

b) the inner discreteness (pluralia tantum, jeans).

To sum it up, all nouns may be subdivided into three groups:

1. The nouns in which the opposition of explicit discreteness/indiscreteness is expressed : cat::cats;

2. The nouns in which this opposition is not expressed explicitly but is revealed by syntactical and lexical correlation in the context. There are two groups here:

A. Singularia tantum. It covers different groups of nouns: proper names, abstract nouns, material nouns, collective nouns;

B. Pluralia tantum. It covers the names of objects consisting of several parts (jeans), names of sciences (mathematics), names of diseases, games, etc.

3. The nouns with homogenous number forms. The number opposition here is not expressed formally but is revealed only lexically and syntactically in the context: e.g. Look! A sheep is eating grass. Look! The sheep are eating grass.

The category of case

Case expresses the relation of a word to another word in the word-group or sentence (my sister’s coat). The category of case correlates with the objective category of possession. The case category in English is realized through the opposition: The Common Case :: The Possessive Case (sister :: sister’s). However, in modern linguistics the term “genitive case” is used instead of the “possessive case” because the meanings rendered by the “`s” sign are not only those of possession. The scope of meanings rendered by the Genitive Case is the following :

a) Possessive Genitive : Mary’s father – Mary has a father,

b) Subjective Genitive: The doctor’s arrival – The doctor has arrived,

c) Objective Genitive : The man’s release – The man was released,

d) Adverbial Genitive : Two hour’s work – X worked for two hours,

e) Equation Genitive : a mile’s distance – the distance is a mile,

f) Genitive of destination: children’s books – books for children,

g) Mixed Group: yesterday’s paper

To avoid confusion with the plural, the marker of the genitive case is represented in written form with an apostrophe. This fact makes possible disengagement of –`s form from the noun to which it properly belongs. E.g.: The man I saw yesterday’s son, where -`s is appended to the whole group (the so-called group genitive). It may even follow a word which normally does not possess such a formant, as in somebody else’s book.

There is no universal point of view as to the case system in English. Different scholars stick to a different number of cases.

1. There are two cases. The Common one and The Genitive;

2. There are no cases at all, the form `s is optional because the same relations may be expressed by the ‘of-phrase’: the doctor’s arrival – the arrival of the doctor;

3. There are three cases: the Nominative, the Genitive, the Objective due to the existence of objective pronouns me, him, whom;

4. Case Grammar. Ch.Fillmore introduced syntactic-semantic classification of cases. They show relations in the so-called deep structure of the sentence. According to him, verbs may stand to different relations to nouns. There are 6 cases:

1) Agentive Case (A) John opened the door;

2) Instrumental case (I) The key opened the door; John used the key to open the door;

3) Dative Case (D) John believed that he would win (the case of the animate being affected by the state of action identified by the verb);

4) Factitive Case (F) The key was damaged ( the result of the action or state identified by the verb);

5) Locative Case (L) Chicago is windy;

6) Objective case (O) John stole the book.

The Problem of Gender in English

Gender plays a relatively minor part in the grammar of English by comparison with its role in many other languages. There is no gender concord, and the reference of the pronouns he, she, it is very largely determined by what is sometimes referred to as ‘natural’ gender for English, it depends upon the classification of persons and objects as male, female or inanimate. Thus, the recognition of gender as a grammatical category is logically independent of any particular semantic association.

According to some language analysts (B. Ilyish, F. Palmer, and E. Morokhovskaya), nouns have no category of gender in Modern English. Prof. Ilyish states that not a single word in Modern English shows any peculiarities in its morphology due to its denoting male or female being. Thus, the words husband and wife do not show any difference in their forms due to peculiarities of their lexical meaning. The difference between such nouns as actor and actress is a purely lexical one. In other words, the category of sex should not be confused with the category of sex, because sex is an objective biological category. It correlates with gender only when sex differences of living beings are manifested in the language grammatically (e.g. tiger – tigress). Still, other scholars (M.Blokh, John Lyons) admit the existence of the category of gender. Prof. Blokh states that the existence of the category of gender in Modern English can be proved by the correlation of nouns with personal pronouns of the third person (he, she, it). Accordingly, there are three genders in English: the neuter (non-person) gender, the masculine gender, the feminine gender.

THE ARTICLE

Students of English will always find it helpful to consult such sources for the study of the articles in English as Oxford English Dictionary and Christophersen's monograph The Articles: a Study of Their Theory and Use.

Questions that cannot be answered one way while speaking about the articles:

1) is the article a separate part of speech (determiner)?

2)is the article a word or a morpheme (auxiliary morpheme)?

The two main views of the article are, then, these:

(1) The article is a word (possibly a separate part of speech) and the collocation "article + noun" is a phrase (if of a peculiar kind).

(2) The article is a form element in the system of the noun; it is thus a kind of morpheme, or if a word, an auxiliary word of the same kind as the auxiliary verbs. In that case the phrase "article + noun" is a morphological formation similar to the formation "auxiliary verb + .+ infinitive or participle", which is an analytical form of the verb.

3) The name "determiners" is given to closed system items, which, functioning as adjuncts, show their head-words to be nouns. Rayevska states, that the most central type of "determiner" is that to which we traditionally give the name article.

According to Blokh, article is also defined as a determining unit? But of a specific nature accompanying the noun in communicative collocation. Its special character is clearly seen against the background of determining words of half-notional semantics. Whereas the function of the determiners such as this, any, some is to explicitly interpret the referent of the noun in relation to other objects or phenomena of a like kind, the semantic purpose of the article is to specify the nounal referent, as it were, altogether unostentatiously, to define it in the most general way, without any explicitly expressed contrasts. For example, Some woman called in your absence, she didn't give her name. (I.e. a woman strange to me.)— A woman called while you were out, she left a message. (I.e. simply a woman, without a further connotation.) Another peculiarity of the article, as different from the determiners in question, is that, in the absence of a determiner, the use of the article with the noun is quite obligatory, in so far as the cases of non-use of the article are subject to no less definite rules than the use of it. Taking into consideration these peculiar features of the article, the linguist is called upon to make a sound statement about its segmental status in the system of morphology. Namely, his task is to decide whether the article is a purely auxiliary element of a special grammatical form of the noun which functions as a component of a definite morphological category, or it is a separate word, i.e. a lexical unit in the determiner word set, if of a more abstract meaning than other determiners.

1. Number and meaning of articles

There are only two material articles, the definite article the and the indefinite article a (an). The distinction thus is between, for instance, the language and a language. However, the noun language, and indeed many other nouns, are also used without any article, as in the sentence Language is a means of communication. It is obvious that the absence of the article in this sentence is in itself a means of showing that "language in general", and not any specific language (such as English, or French, etc.), is meant. Hence we may say that there are three variants: (1) the language, (2) a language, (3) language. The last one is sometimes called a 'zero article'. Theidea of a zero article takes its origin in the notion of "zero morpheme", which has been applied to in English, for instance, to the singular form of nouns (room) as distinct from the plural form with its -s-inflection. If, therefore, we were to interpret the article as a morpheme, the idea of a zero article would make no difficulty. If, on the other hand, we take the article to be a word, the idea of a "zero word" would entail some difficulty.

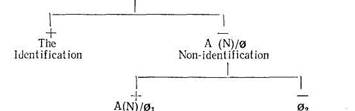

The article determination of the noun should be divided into two binary correlations connected with each other hierarchically.

The opposition of the higher level operates in the whole system of articles. It contrasts the definite article with the noun against the two other forms of article determination of the noun, i.e. the indefinite article and the meaningful absence of the article. In this opposition the definite article should be interpreted as the strong member by virtue of its identifying and individualising function, while the other forms of article determination should be interpreted as the weak member, i.e. the member that leaves the feature in question ("identification") unmarked.

The opposition of the lower level operates within the article subsystem that forms the weak member of the upper opposition. This opposition contrasts the two types of generalisation, i.e. the relative generalisation distinguishing its strong member (the indefinite article plus the meaningful absence of the article as its analogue with uncountable nouns and nouns in the plural) and the absolute, or "abstract" generalisation distinguishing the weak member of the opposition (the meaningful absence of the article).

The described oppositional system can be shown on the following diagram (see Fig. 1).

|

| ARTICLE DETERMINATION |

Relative Generalisation Absolute Generalisation

("Classification") ("Abstraction")

Fig. 1

The best way of demonstrating the actual oppositional value of the articles on the immediate textual material is to contrast them in syntactically equivalent conditions in pairs. Cf. the examples given below.

Identical nounal positions for the pair "the definite article — the indefinite article": The train hooted (that train). — A train hooted (some train).

Correlative nounal positions for the pair "the definite article — the absence of the article": I'm afraid the oxygen is out (our supply of oxygen). — Oxygen is necessary for life (oxygen in general, life in general).

Correlative nounal positions for the pair "the indefinite article — the absence of the article": Be careful, there is a puddle under your feet (a kind of puddle).— Be careful, there is mud on the ground (as different from clean space).

Finally, correlative nounal positions for the easily neutralised pair "the zero article of relative generalisation — the zero article of absolute generalisation": New information should be gathered on this subject (some information). — Scientific information should be gathered systematically in all fields of human knowledge (information in general).

THE VERB

1. General characteristics

Grammatically the verb is the most complex part of speech. First of all it performs the central role in realizing predication - connection between situation in the utterance and reality. That is why the verb is of primary informative significance in an utterance. Besides, the verb possesses quite a lot of grammatical categories. Furthermore, within the class of verb various subclass divisions based on different principles of classification can be found.

Semantic features of the verb. The verb possesses the grammatical meaning of verbiality - the ability to denote a process developing in time. This meaning is inherent not only in the verbs denoting processes, but also in those denoting states, forms of existence, evaluations, etc.

Morphological features of the verb. The verb possesses the following grammatical categories: tense, aspect, voice, mood, person, number, finitude and phase. The common categories for finite and non-finite forms are voice, aspect, phase and finitude. The grammatical categories of the English verb find their expression in synthetical and analytical forms. The formative elements expressing these categories are grammatical affixes, inner inflexion and function words. Some categories have only synthetical forms (person, number), others - only analytical (voice). There are also categories expressed by both synthetical and analytical forms (mood, tense, aspect).

Syntacticfeatures. The most universal syntactic feature of verbs is their ability to be modified by adverbs. The second important syntactic criterion is the ability of the verb to perform the syntactic function of the predicate. However, this criterion is not absolute because only finite forms can perform this function while non-finite forms can be used in any function but predicate. And finally, any verb in the form of the infinitive can be combined with a modal verb.

2. Classifications of English verbs

According to different principles of classification, classifications can be morphological, lexical-morphological, syntactical and functional.

A.Morphological classifications.

I. According to their stem-types all verbs fall into:

simple (to go),

sound-replacive (food - to feed, blood - to bleed),

stress-replacive (import - to import, transport - to transport),

expanded (with the help of suffixes and prefixes): cultivate, justify, overcome,

composite (correspond to composite nouns): to blackmail),

phrasal: to have a smoke, to give a smile (they always have an ordinary verb as an equivalent). 2. According to the way of forming past tenses and Participle II verbs can be regular and irregular.

B.Lexical-morphological classification is based on the implicit grammatical meanings of the verb.

According to the implicit grammatical meaning of transitivity/intransitivity verbs fall into transitive and intransitive.

According to the implicit grammatical meaning of stativeness/non-stativeness verbs fall into stative and dynamic.

According to the implicit grammatical meaning of terminativeness/non-terminativeness verbs fall into terminative and durative. This classification is closely connected with the categories of Aspect and Phase.

C. Syntactic classifications.

According to the nature of predication (primary and secondary) all verbs fall into finite and non-finite.

According to syntagmatic properties (valency) verbs can be of obligatory and optional valency, and thus they may have some directionality or be devoid of any directionality. In this way, verbs fall into the verbs of directed (to see, to take, etc.) and non-directed action (to arrive, to drizzle, etc.):

D. Functionalclassification.

According to their functional significance verbs can be notional (with the full lexical meaning), semi-notional (modal verbs, link-verbs), auxiliaries.

3. The category of voice

The form of the verb may show whether the agent expressed by the subject is the doer of the action or the recipient of the action (John broke the vase - the vase was broken). The objective relations between the action and the subject or object of the action find their expression in language as the grammatical category of voice. Therefore, the category of voice reflects the objective relations between the action itself and the subject or object of the action:

The category of voice is realized through the opposition Active voice::Passive voice. The realization of the voice category is restricted because of the implicit grammatical meaning of transitivity/intransitivity. In accordance with this meaning, all English verbs should fall into transitive and intransitive. However, the classification turns out to be more complex and comprises 6 groups:

1. Verbs used only transitively: to mark, to raise;

2.Verbs with the main transitive meaning: to see, to make, to build;

3. Verbs of intransitive meaning and secondary transitive meaning. A lot of intransitive verbs may develop a secondary transitive meaning: They laughed me into agreement; He danced the girl out of the room;

4.Verbs of a double nature, neither of the meanings are the leading one, the verbs can be used both transitively and intransitively: to drive home - to drive a car;

5.Verbs that are never used in the Passive Voice: to seem, to become;

6. Verbs that realize their passive meaning only in special contexts: to live, to sleep, to sit, to walk, to jump.

Some scholars admit the existence of Middle, Reflexive and Reciprocal voices. "Middle Voice" - the verbs primarily transitive may develop an intransitive middle meaning: That adds a lot; The door opened; The book sells easily; The dress washes well. "Reflexive Voice": He dressed; He washed - the subject is both the agent and the recipient of the action at the same time. It is always possible to use a reflexive pronoun in this case: He washed himself. "Reciprocal voice”: They met; They kissed - it is always possible to use a reciprocal pronoun here: They kissed each other.

We cannot, however, speak of different voices, because all these meanings are not expressed morphologically.

4. The category of tense

The category of tense is a verbal category that reflects the objective category of time. The essential characteristic of the category of tense is that it relates the time of the action, event or state of affairs referred to in the sentence to the time of the utterance (the time of the utterance being 'now ' or the present moment). The tense category is realized through the oppositions. The binary principle of oppositions remains the basic one in the correlation of the forms that represent the grammatical category of tense. The present moment is the main temporal plane of verbal actions. Therefore, the temporal dichotomy may be illustrated by the following graphic representation (the arrows show the binary opposition):

Present Past

|  | ||

Future I Future II

Generally speaking, the major tense-distinction in English is undoubtedly that which is traditionally described as an opposition of past::present. But this is best regarded as a contrast of past:: non-past. Quite a lot of scholars do not recognize the existence of future tenses, because what is described as the 'future' tense in English is realized by means of auxiliary verbs will and shall. Although it is undeniable that will and shall occur in many sentences that refer to the future, they also occur in sentences that do not. And they do not necessarily occur in sentences with a future time reference. That is why future tenses are often treated as partly modal.

5. The Category of Aspect

The category of aspect is a linguistic representation of the objective category of Manner of Action. It is realized through the opposition Continuous::Non-Continuous (Progressive::Non-Progressive). The realization of the category of aspect is closely connected with the lexical meaning of verbs.

There are some verbs in English that do not normally occur with progressive aspect, even in those contexts in which the majority of verbs necessarily take the progressive form. Among the so-called ‘non-progressive’ verbs are think, understand, know, hate, love, see, taste, feel, possess, own, etc. The most striking characteristic that they have in common is the fact that they are ‘stative’ - they refer to a state of affairs, rather than to an action, event or process. It should be observed, however, that all the ‘non-progressive' verbs take the progressive aspect under particular circumstances. As the result of internal transposition verbs of non-progressive nature can be found in the Continuous form: Now I'm knowing you. Generally speaking the Continuous form has at least two semantic features - duration (the action is always in progress) anddefiniteness (the action is always limited to a definite point or period of time). In other words, the purpose of the Continuous form is to serve as a frame which makes the process of the action more concrete and isolated.

THE ADJECTIVE

General Characteristics

While traditional grammars usuallydefine nouns and verbs semantically, they often shift to functional criteria to characterize adjectives. For example, Rayevska defines anadjective as a word which expresses the attributes of substances (good, young, easy, soft, loud, hard, wooden, flaxen). As a class of lexical words adjectives are identified by their ability to fill the position between noun-determiner and noun and the position after a copula-verb and a qualifier.

Semantic features of the adjective.The adjective expresses property or quality of a substance. According to Blokh, each adjective used in the text, presupposes relation to some noun the property of whose referent it denotes, such as material, colour, dimensions, position, state, and other characteristics both permanent and temporary. It follows from this that, unlike nouns, adjectives do not possess a full nominative value. Indeed, words like long, hospitable, fragrant cannot affect any self-dependent nominations; as units of informative sequences they exist only in collocations showing what is long, who is hospitable, what is fragrant.

Considered in meaning, adjectives fall into two large groups:

a) qualitative adjectives,

b) relative adjectives.

Qualitative adjectivesdenote qualities of size, shape, colour, etc. which an object may possess in various degrees. Qualitative adjectives have degrees of comparison.

Relative adjectivesexpress qualities which characterise an object through its relation to another object; wooden tables → tables made of wood, woollen gloves → gloves made of wool, Siberian wheat → wheat from Siberia. Further examples of relative adjectives are: rural, industrial, urban, etc.

Linguistically it is utterly impossible to draw a rigid line of demarcation between the two classes, for in the course of language development the so-called relative adjectives gradually develop qualitative meanings. Thus, for instance, through metaphoric extension adjectives denoting material have come to be used in the figurative sense, e. g.: golden age золотий вік, golden hours щасливий час, golden mean золота середина, golden opportunity чудова нагода, golden hair золотаве волосся, etc.

Morphological features of the adjective. Adjectives in Modern English are invariable. As is well known, it has neither number, nor case, nor gender distinctions. Some adjectives have, however, degrees of comparison, which make part of the morphological system of a language. It seems practical to distinguish between base adjectives and derived adjectives.

Base adjectivesexhibit the following formal qualities: they may take inflections -er and -est or have some morphophonemic changes in cases of the suppletion, such as, for instance, in good —better —the best; bad — worse — the worst. Base adjectives are also distinguished formally by the fact that they serve as stems from which nouns and adverbs are formed by the derivational suffixes -ness and -ly.

Base adjectives are mostly of one syllable, and none have more than two syllables except a few that begin with a derivational prefix un-or in-, e. g.: uncommon, inhuman, etc. They have no derivational suffixes and usually form their comparative and superlative degrees by means of the inflectional suffixes -er and -est. Quite a number of based adjectives form verbs by adding the derivational suffix -en, the prefix en- or both: blacken, brighten, cheapen, sweeten, widen, enrich, enlarge, embitter, enlighten, enliven, etc.

Derived adjectivesare formed by the addition of derivational suffixes to free or bound stems. They usually form analytical comparatives and superlatives by means of the qualifiers more and most. Some of the more important suffixes which form derived adjectives are:

-ableadded to verbs and bound stems, denoting quality with implication of capacity, fitness or worthness to be acted upon; -able is often used in the sense of "tending to", "given to", "favouring", "causing", "able to" or "liable to". This very common suffix is a live one which can be added to virtually any verb thus giving rise to many new coinages. As it is the descendant of an active derivational suffix in Latin, it also appears as a part of many words borrowed from Latin and French. Examples formed from verbs: remarkable, adaptable, conceivable, drinkable, eatable, regrettable, understandable, etc.; examples formed from bound stems: capable, portable, viable. The unproductive variant of the suffix -able is the suffix -ible (Latin -ibilis, -bilis), which we find in adjectives Latin in origin: visible, forcible, comprehensible, etc.; -ible is no longer used in the formation of new words.

-al, -ial(Lat. -alls, French -al, -el) denoting quality "belonging to", "pertaining to", "having the character of", "appropriate to", e. g.: elemental, bacterial, automnal, fundamental, etc.

The suffix -al added to nouns and bound stems (fatal, local, natural, national, traditional, etc.) is often found in combination with -ic, e. g.: biological, botanical, juridical, typical, etc.

-ish—Germanic in origin, denoting nationality, quality with the meaning "of the nature of", "belonging to", "resembling" also with the sense "somewhat like", often implying contempt, derogatory in force, e. g.: Turkish, bogish, outlandish, whitish, wolfish.

-y — Germanic in origin, denoting quality "pertaining to", "abounding in", "tending or inclined to", e.g.: rocky, watery, bushy, milky, sunny, etc.

Syntacticfeatures. (a) Adjectives combine with nouns both preceding and (occasionally) following them (large room, times immemorial). They also combine with a preceding adverb (very large). Adjectives can be followed by the phrase "preposition + noun" (free from danger). Occasionally they combine with a preceding verb (married young). (b) In the sentence, an adjective can be either an attribute (large room) or a predicative (is large). It can also be an objective predicative (painted the door green).

The Category of Intensity and Comparison

1) how many degrees of comparison has the English adjective?

If we take, for example, the three forms of an English adjective: large, larger, (the) largest, shall we say that they are, all three of them, degrees of comparison? In that case we ought to term them positive, comparative, and superlative. Or shall we say that only the latter two are degrees of comparison (comparative and superlative), whereas the first (large), does not express any idea of comparison and is therefore not a degree of comparison at all? Both views have found their advocates in grammatical theory.

Now it is well known that not every adjective has degrees of comparison. This may depend on two factors. One of these is not grammatical, but semantic. Since degrees of comparison express a difference of degree in the same property, only those adjectives admit of degrees of comparison which denote properties capable of appearing in different degrees. Thus, it is obvious that, for example, the adjective middle has no degrees of comparison. The same might be said about many other adjectives, such as blind, deaf, dead, etc. However, this should not be taken too absolutely. Occasionally we may meet with such a sentence as this: You cannot be deader than dead.

2) A more complex problem in the sphere of degrees of comparison is that of the formations more difficult, (the) most difficult, or more beautiful, (the) most beautiful. The question is this: is more difficult an analytical comparative degree of the adjective difficult? In that case the word more would be an auxiliary word serving to make up that analytical form, and the phrase would belong to the sphere of morphology. Or is more difficult a free phrase, not different in its essential character from the phrase very difficult or somewhat difficult"? In that case the adjective difficult would have no degrees of comparison at all (forming degrees of comparison of this adjective by means of the inflections -er, -est isimpossible), and the whole phrase would be a syntactical formation. The traditional view held both by practical and theoretical grammars until recently was that phrases of this type were analytical degrees of comparison. Recently, however, the view has been put forward that they do not essentially differ from phrases of the type very difficult, which, of course, nobody would think of treating as analytical forms.

Let us examine the arguments that have been or may be put forward in favour of one and the other view.

The view that formations of the type more difficult are analytical degrees of comparison may be supported by the following considerations: (1) The actual meaning of formations like more difficult, (the) most difficult does not differ from that of the degrees of comparison larger, (the) largest. (2) Qualitative adjectives, like difficult, express properties which may be present in different degrees, and therefore they are bound to have degrees of comparison.

The argument against such formations being analytical degrees of comparison would run roughly like this. No formation should be interpreted as an analytical form unless there are compelling reasons for it, and if there are considerations contradicting such a view. Now, in this particular case there are such considerations: (1) The words more and most have the same meaning in these phrases as in other phrases in which they may appear, e. g. more time, most people, etc. (2) Alongside of the phrases more difficult, (the) most difficult there are also the phrases less difficult, (the) least difficult, and there seems to be no sufficient reason for treating the two sets of phrases in different ways, saying that more difficult is an analytical form, while less difficult is not. Besides, the very fact that more and less, (the) most and (the) least can equally well combine with difficult, would seem to show that they are free phrases and none of them is an analytical form. The fact that more difficult stands in the same sense relation to difficult as larger to large is of course certain, but it should have no impact on the interpretation of the phrases more difficult, (the) most difficult from a grammatical viewpoint.

Taking now a general view of both lines of argument, we can say that, roughly speaking, considerations of meaning tend towards recognising such formations as analytical forms, whereas strictly grammatical considerations lead to the contrary view.

A few adjectives do not, as is well known, form any degrees of comparison by means of inflections. Their degrees of comparison are derived from a different root. These are good, better, best; bad, worse, worst, and a few more. Should these formations be acknowledged as suppletive forms of the adjectives good, bad, etc., or should they not? There seems no valid reason for denying them that status. The relation good: better = large: larger is indeed of the same kind as the relation go: went = live: lived, where nobody has expressed any doubt about went being a suppletive past tense form of the verb go. Thus, it is clear enough that there is every reason to take better, worse, etc., as suppletive degrees of comparison to the corresponding adjectives.

THE ADVERB

Semantic features. The meaning of the adverb as a part of speech is hard to define. Indeed, some adverbs indicate time or place of an action (yesterday, here), while others indicate its property (quickly) and others again the degree of a property (very). As, however, we should look for one central meaning characterising the part of speech as a whole, it seems best to formulate the meaning of the adverb as "property of an action or of a property".

Morphological features. Adverbs are invariable. Some of them, however, have degrees of comparison (fast, faster, fastest).

Syntactic features. (a) An adverb combines with a verb (run quickly), with an adjective (very long), occasionally with a noun (the then president) and with a phrase (so out of things). (b) An adverb can sometimes follow a preposition (from there). (c) In a sentence an adverb is almost always an adverbial modifier, or part of it (from there), but it may occasionally be an attribute.

THE PRONOUN

Semantic features. The meaning of the pronoun as a separate part of speech is somewhat difficult to define. In fact, some pronouns share essential peculiarities of nouns (e.g. he), while others have much in common with adjectives (e. g. which). This made some scholars think that pronouns were not a separate part of speech at all and should be distributed between nouns and adjectives. However, this view proved untenable and entailed insurmountable difficulties. Hence it has proved necessary to find a definition of the specific meaning of pronouns, distinguishing them from both nouns and adjectives. From this angle the meaning of pronouns as a part of speech can be stated as follows: pronouns point to the things and properties without naming them. Thus, for example, the pronoun it points to a thing without being the name of any particular class of things. The pronoun its points to the property of a thing by referring it to another thing. The pronoun what can point both to a thing and a property.

| Pronoun Type | Members of the Subclass | Example |

| Possessive | mine, yours, his, hers, ours, theirs | The white car is mine |

| Reflexive | myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, oneself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves | He injured himself playing football |

| Reciprocal | each other, one another | They really hate each other |

| Relative | that, which, who, whose, whom, where, when | The book that you gave me was really boring |

| Demonstrative | this, that, these, those | This is a new car |

| Interrogative | who, what, why, where, when, whatever | What did he say to you? |

| Indefinite | anything, anybody, anyone, something, somebody, someone, nothing, nobody, none, no one | There's something in my shoe |

Morphological features. As far as form goes pronouns fall into different types. Some of them have the category of number (singular and plural), e. g. this, while others have no such category, e. g. somebody. Again, some pronouns have the category of case (he — him, somebody — somebody's), while others have none (something).

Syntactic features. (a) Some pronouns combine with verbs (he speaks, find him), while others can also combine with a following noun (this room). (b) In the sentence, some pronouns may be the subject (he, what) or the object, while others are the attribute (my). Pronouns can be predicatives.

THE NUMERAL

The treatment of numerals presents some difficulties, too. The so-called cardinal numerals (one, two) are somewhat different from the so-called ordinal numerals (first, second).

Semantic features. Numerals denote either number or place in a series.

Morphological features. Numerals are invariable.

Syntactic features. (a) As far as phrases go, both cardinal and ordinal numerals combine with a following noun (three rooms, third room); occasionally a numeral follows a noun (soldiers three, George the Third). (b) In a sentence, a numeral most usually is an attribute (three rooms, the third room), but it can also be subject, predicative, and object: Three of them came in time; "We Are Seven" (the title of a poem by Wordsworth); I found only four.

THE PREPOSITION

The problem of prepositions has caused very heated discussions, especially in the last few years. Both the meaning and the syntactical functions of prepositions have been the subject of controversy.

Semantic features. The meaning of prepositions is obviously that of relations between things and phenomena.

Morphological features. Prepositions are invariable.

Syntactic features. Prepositions enter into phrases in which they are preceded by a noun, adjective, numeral, verb or adverb, and followed by a noun, adjective, numeral or pronoun. (b) In a sentence a preposition never is a separate part of it. It goes together with the following word to form an object, adverbial modifier, predicative or attribute, and in extremely rare cases a subject (There were about a hundred people in the hall).

THE CONJUNCTION

The problem of conjunctions is of the same order as that of prepositions, but it has attracted less attention.

Semantic features.Conjunctions express connections between things and phenomena.

Morphological features. Conjunctions are invariable.

Syntactic features. (a) They connect any two words, phrases or clauses. (b) In a sentence, conjunctions are never a special part of it. They either connect homogeneous parts of a sentence or homogeneous clauses (the so-called co-ordinating conjunctions), or they join a subordinate clause to its head clause (the so-called subordinating conjunctions).

A further remark is necessary here. We have said that prepositions express relations between phenomena, and conjunctions express connections between them. It must be acknowledged that the two notions, relations and connections, are somewhat hard to distinguish. This is confirmed by the well-known fact that phrases of one and the other kind may be more or less synonymous: cf., e. g., an old man and his son and an old man with his son. It is also confirmed by the fact that in some cases a preposition and a conjunction may be identical in sound and have the same meaning (e. g. before introducing a noun and before introducing a subordinate clause; the same about after). Since it is hard to distinguish between prepositions and conjunctions as far as meaning goes, and morphologically they are both invariable, the only palpable difference between them appears to be their syntactical function. It may be reasonably doubted whether this is a sufficient basis for considering them to be separate parts of speech. It might be argued that prepositions and conjunctions make up a single part of speech, with subdivisions based on the difference of syntactical functions. Such a view would go some way toward solving the awkward problem of homonymy with reference to such words as before, after, since, and the like. However, since this is an issue for further consideration, we will, for the time being, stick to the traditional view of prepositions and conjunctions as separate parts of speech.

THE PARTICLE

By particles we mean such word as only, solely, exclusively, even (even old people came), just (just turn the handle), etc. These were traditionally classed with adverbs, from which they, however, differ in more than one respect.

Semantic features. The meaning of particles is very hard to define. We might say, approximately, that they denote subjective shades of meaning introduced by the speaker or writer and serving to emphasise or limit some point in what he says.

Morphological features. Particles are invariable.

Syntactic features. (a) Particles may combine with practically every part of speech, more usually preceding it (only three), but occasionally following it (for advanced students only). (b) Particles never are a separate part of a sentence. They enter the part of the sentence formed by the word (or phrase) to which they refer. (It might also be argued that particles do not belong to any part of a sentence.)

MODAL WORD

Modal words have only recently been separated from adverbs, with which they were traditionally taken together. By modal words we mean such words as perhaps, possibly, certainly.

Semantic features. Modal words express the speaker's evaluation of the relation between an action and reality.

Morphological features. Modal words are invariable.

Syntactic features. (a) Modal words usually do not enter any phrases but stand outside them. In a few cases, however, they may enter into a phrase with a noun, adjective, etc. (he will arrive soon, possibly to-night). (b) The function of modal words in a sentence is a matter of controversy. We will discuss this question at some length in Chapter XXI and meanwhile we will assume that modal words perform the function of a parenthesis. Modal words may also be a sentence in themselves.

THE INTERJECTION

Semantic features. Interjections express feelings (ah, alas). They are not names of feelings but the immediate expression of them. Some interjections represent noises, etc., with a strong emotional colouring (bang!).

Morphological features. Interjections are invariable.

Syntactic features. (a) Interjections usually do not enter into phrases. Only in a few cases do they combine with a preposition and noun or pronoun, e.g. alas for him! (b) In a sentence an interjection forms a kind of parenthesis. An interjection may also be a sentence in itself, e. g. Alas! as an answer to a question.

So far we have been considering parts of speech as they are usually termed and treated in grammatical tradition: we have been considering nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc. Some modern linguists prefer to avoid this traditional grouping and terminology and to establish a classification of types of words based entirely on their morphological characteristics and on their ability (or inability) to enter into phrases with other words of different types.

| <== предыдущая лекция | | | следующая лекция ==> |

| Ordinary repetition | | | General characteristics and classification |

Дата добавления: 2016-08-07; просмотров: 7913;