The Middle Ages and The Renaissance

Text Bridge

Bridgeis a structure used by people and vehicles to cross areas that are obstacles to travel. Engineers build bridges over lakes, rivers, canyons, and busy highways and railroad tracks. Without bridges, people would need boats to cross waterways and would have to travel around such obstacles as canyons and ravines.

Bridges range in length from a few feet or meters to several miles or kilometers. A bridge must be strong enough to support its own weight as well as the weight of the people and vehicles that use it. It also must resist natural occurrences, including earthquakes, strong winds, and changes in temperature. Most modern bridges have a concrete, steel, or wood framework and an asphalt or concrete roadway. The roadway is the part of a bridge on which people and vehicles travel.

Most bridges are held up by at least two supports set in the ground. The distance between two adjacent supports is called a span of a bridge. The supports at each end of the bridge are called abutments, and the supports that stand between the abutments are called piers. The total length of the bridge is the distance between the abutments. Most short bridges are supported only by abutments and are known as single-span bridges. Bridges that have one or more piers in addition to the abutments are called multi-span bridges. Most long bridges are multi-span bridges. The main span is the longest span of a multi-span bridge.

The prototypical bridge is quite simple—two supports holding up a beam—yet the engineering problems that must be overcome even in this simple form are inherent in every bridge: the supports must be strong enough to hold the structure up, and the span between supports must be strong enough to carry the loads. Spans are generally made as short as possible; long spans are justified where good foundations are limited—for example, over estuaries with deep water. A pontoon bridge has no piers or abutments. It is supported by pontoons (flat-bottomed boats) or other portable floats.

Some special types of bridges are defined according to their function. An overpass allows one transportation route, such as a highway or railroad line, to cross over another without traffic interference between the two routes. The overpass elevates one route to provide clearance to traffic on the lower level. An aqueduct transports water. Aqueducts have historically been used to supply drinking water to densely populated areas. A viaduct carries a railroad or highway over a land obstruction, such as a valley.

All major bridges are built with the public's money. Therefore, bridge design that best serves the public interest has a threefold goal: to be as efficient, as economical, and as elegant as is safely possible. Efficiency is a scientific principle that puts a value on reducing materials while increasing performance. Economy is a social principle that puts value on reducing the costs of construction and maintenance while retaining efficiency. Finally, elegance is a symbolic or visual principle that puts value on the personal expression of the designer without compromising performance or economy. There is little disagreement over what constitutes efficiency and economy, but the definition of elegance has always been controversial.

Modern designers have written about elegance or aesthetics since the early 19th century, beginning with the Scottish engineer Thomas Telford. Bridges ultimately belong to the general public, which is the final arbiter of this issue, but in general there are three positions taken by professionals.

The first principle holds that the structure of a bridge is the province of the engineer and that beauty is achieved only by architecture.

The second idea insists that bridges making the most efficient possible use of materials are by definition beautiful.

The third case holds that architecture is not needed but that engineers must think about how to make the structure beautiful. This last principle recognizes the fact that engineers have many possible choices of roughly equal efficiency and economy and can therefore express their own aesthetic ideas without adding significantly to materials or cost.

The History of Bridge Building (General Information)

Logs or vines that extended across streams probably served as the first bridges. From this at a later stage, a bridge on a very simple bracket or cantilever principle was evolved. Timber beams were embedded into the banks on each side of the river with their ends extending over the water. These made simple supports for a central beam reaching across from one bracket to the other. Bridges of this type are still used in Japan, and in India. A simple bridge on the suspension principle was made by early man by means of ropes, and is still used in countries such as Tibet. Two parallel ropes suspended from rocks or trees on each bank of the river, with a platform of woven mats laid across them made a secure crossing. Further ropes as handrails were added. When the Spaniards reached South America, they found that the Incas of Peru used suspension bridges made of six strong cables, four of which supported a platform and two served as rails.

The first bridge known to historians was an arch bridge built in Babylon about 2200 B.C. The ancient Chinese, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans also built arch bridges, using bricks and stone as building materials.

During the Middle Ages, moveable bridges called drawbridges were built across the moats of many castles in Europe. Truss bridges were developed in the 1500’s. Most bridges were made of stone or wood until the late 1700's, when cast iron and wrought iron were first used for bridges. Many suspension bridges that hung from wrought iron chains were built in the early 1800's. Between 1830 and 1880, as railroad building expanded throughout the world, bridge design and construction were aimed to carry these heavy vehicles over new obstacles.

Designers experimented with a wide variety of bridge types and had to meet the demand for greater heights, spans, and strength. Locomotives were heavier and moved faster than anything requiring stronger bridges. The basic beam bridge was strengthened by adding support piers underneath and by reinforcing the structure with elaborate scaffolding called a truss. During the period of railroad expansion iron trusses replaced stone arches as the preferred design large bridges.

The first plate girder bridge was completed in 1847, and the modern cantilever bridge was introduced about 1870. In the late 1800s, steel became the chief material used in bridge construction.

In 1855 British inventor Sir Henry Bessemer developed a practical process for converting cast iron into steel. This process increased the availability of steel and lowered production costs considerably. The strength and lightness of steel revolutionized bridge building. In the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, many large-scale steel suspension bridges were constructed over major waterways in the late 19th century, engineers began to experiment with concrete reinforced with steel bars for added strength. More recently, reinforced concrete has been combined with steel girders, which are solid beams that extend across a span. When the Interstate Highway System in the United States and similar road systems in other countries were constructed in the mid- to late 20th century, the steel-and-concrete girder bridge was one of the most commonly used bridge designs. The last three decades of the 20th century saw a period of large-scale bridge building in Europe and Asia. Current research focuses on using computers, instrumentation, automation, and new materials to improve bridge design, construction, and maintenance.

Beam bridges.

The first bridges were simply supported by beams, such as flat stones or tree trunks laid across a stream.

For valleys and other wider channels—especially in East Asia and South America, where examples can still be found—ropes made of various grasses and vines tied together were hung in suspension for single-file crossing.

Materials were free and abundant, and there were few labour costs, since the work was done by slaves, soldiers, or natives who used the bridges in daily life.

Some of the earliest known bridges are called clapper bridges (from Latin claperius, "pile of stones"). These bridges were built with long, thin slabs of stone to make a beam-type deck and with large rocks or blocklike piles of stones for piers. Postbridge in Devon, Eng., an early medieval clapper bridge, is an oft-visited example of this old type, which was common in much of the world, especially China.

Roman arch bridges.

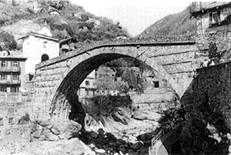

Ponte Saint-Martin (c 25 BC) near Torino (Italy). Shunsuke Baba, photographer Ponte Saint-Martin (c 25 BC) near Torino (Italy). Shunsuke Baba, photographer

|

The Romans began organized bridge building to help their military campaigns. Engineers and skilled workmen formed guilds that were dispatched throughout the empire, and these guilds spread and exchanged building ideas and principles. The Romans also discovered a natural cement, called pozzolana, which they used for piers in rivers. Roman bridges are famous for using the circular arch form, which allowed for spans much longer than stone beams and for bridges of more permanence than wood. Where several arches were necessary for longer bridges, the building of strong piers was critical. This was a problem when the piers could not be built on rock, as in a wide river with a soft bed. To solve this dilemma, the Romans developed the cofferdam, a temporary enclosure made from wooden piles driven into the riverbed to make a sheath, which was often sealed with clay. Concrete was then poured into the water within the ring of piles. Although most surviving Roman bridges were built on rock, the Sant'Angelo Bridge in Rome stands on cofferdam foundations built in the Tiber River more than 1,800 years ago.

Asian cantilever and arch bridges.

In Asia, wooden cantilever bridges were popular. The basic design used piles driven into the riverbed and old boats filled with stones sunk between them to make cofferdam-like foundations. When the highest of the stone-filled boats reached above the low-water level, layers of logs were crisscrossed in such a way that, as they rose in height, they jutted farther out toward the adjacent piers. At the top, the Y-shaped, cantilevering piers were joined by long tree trunks. By crisscrossing the logs, the builders allowed water to pass through the piers, offering less resistance to floods than with a solid design. In this respect, these designs presaged some of the advantages of the early iron bridges.

In parts of China many bridges had to stand in the spongy silt of river valleys. As these bridges were subject to an unpredictable assortment of tension and compression, the Chinese created a flexible masonry-arch bridge. Using thin, curved slabs of stone, the bridges yielded to considerable deformation before failure.

The Middle Ages and The Renaissance

After the fall of the Roman Empire, progress in European bridge building slowed considerably until the Renaissance. Fine bridges sporadically appeared, however. Medieval bridges are particularly noted for the ogival, or pointed arch. With the pointed arch the tendency to sag at the crown is less dangerous, and there is less horizontal thrust at the abutments. Medieval bridges served many purposes. Chapels and shops were commonly built on them, and many were fortified with towers and ramparts. Some featured a drawbridge, a medieval innovation. The most famous bridge of that age was Old London Bridge, begun in the late 12th century under the direction of a priest, Peter of Colechurch, and completed in 1209, four years after his death. London Bridge was designed to have 19 pointed arches, each with a 24-foot span and resting on piers 20 feet wide. There were obstructions encountered in building the cofferdams, however, so that the arch spans eventually varied from 15 to 34 feet. The uneven quality of construction resulted in a frequent need for repair, but the bridge held a large jumble of houses and shops and survived more than 600 years before being replaced. A more elegant bridge of the period was the Saint-Benezet Bridge at Avignon, Fr. Begun in 1177, part of it still stands today. Another medieval bridge of note is Monnow Bridge in Wales, which featured three separate ribs of stone under the arches. Rib construction reduced the quantity of material needed for the rest of the arch and lightened the load on the foundations.

During the Renaissance, the Italian architect Andrea Palladio took the principle of the truss, which previously had been used for roof supports, and designed several successful wooden bridges with spans up to 100 feet. Longer bridges, however, were still made of stone. Another Italian designer, Bartolommeo Ammannati, adapted the medieval ogival arch by concealing the angle at the crown and by starting the curves of the arches vertically in their springings from the piers. This elliptical shape of arch, in which the rise-to-span ratio was as low as 1:7, became known as basket-handled and has been adopted widely since. Ammannati's elegant Santa Trinita Bridge (1569) in Florence, with two elliptical arches, carried pedestrians and later automobiles until it was destroyed during World War II; it was afterward rebuilt with many of the original materials recovered from the riverbed. Yet another Italian, Antonio da Ponte, designed the Rialto Bridge (1591) in Venice, an ornate arch made of two segments with a span of 89 feet and a rise of 21 feet. Antonio overcame the problem of soft, wet soil by having 6,000 timber piles driven straight down under each of the two abutments, upon which the masonry was placed in such a way that the bed joints of the stones were perpendicular to the line of thrust of the arch. This innovation of angling stone or concrete to the line of thrust has been continued into the present.

Дата добавления: 2016-02-20; просмотров: 1424;