THE NEW PHILANTHROPISTS

Laywomen were important contributors as well to the expansion of philanthropy in the late imperial decades. This was a time when philanthropy across Europe was ceasing to be the purview of privileged volunteers and becoming professionalized. In the early 1890s, the municipal government of Moscow took an important step in that direction by creating “guardianships of the poor,” staffed mainly by volunteers who got to know needy families, provided assistance and referrals to social services, stayed in touch to see how the people were getting on, and reported to the government on slum conditions. These were Russia’s first social workers; two‑thirds of them were women. Within a few years, the national government established the National Guardianship to set up workhouses and workshops that provided lodging and job training to the needy. Wealthy women raised money to support the workhouses and found markets for the goods manufactured by the residents. The Guardianship’s employees also fanned out to rural areas, bringing food, organizing public‑works projects that provided employment, and running daycare centers for peasant children. Teachers and female landowners enlisted in all these efforts; they were particularly valuable in the daycare programs.5

Female philanthropists also continued to work in private organizations. The Russian Society for the Protection of Women provided low‑cost housing, medical care, and job training and publicized the problems of poor women, particularly prostitutes. The Red Cross, staffed by many female volunteers, set up nursing courses. Local charitable societies across the empire supported free clinics and libraries, midwifery and nursing schools, night and Sunday schools, and public lectures. In working‑class neighborhoods, they also founded “people’s houses” similar to the settlement houses of Great Britain and the United States.

SOPHIA PANINA (1871–1956)

One of the most famous of the people’s houses was run by Sophia Panina in St. Petersburg. A noblewoman, Panina had inherited an enormous fortune; after a brief, unhappy marriage, she turned to full‑time philanthropy. “My interests,” she wrote many years later, “were concentrated on questions of general education and culture, which alone, I was deeply convinced, could provide a solid basis for a free political order.” In 1903 Panina took over leadership of a people’s house in the working‑class Ligovskii district of St. Petersburg and began building it into an energetic presence in the neighborhood. The institution provided activities for children, a cafeteria, elementary education and vocational training, a medical clinic, meeting rooms, public lectures, a reading room, a savings bank, temporary housing, and a theater. Counselors were available to give advice on legal problems.6

Panina saw herself as a no‑nonsense, hands‑on manager who was offering poor people opportunities to improve their lives. She was demanding and bossy and, like so many of the assertive noblewomen in Russia’s past, she expected to get her own way. Often she did. Her dedication to the neighborhood, her generosity, and her effectiveness earned the respect and gratitude of her clients. They called her center “Panina’s House.” It became a model for similar institutions across the empire.7

THE ARTISTS

Women substantially expanded their participation in Russia’s arts and letters in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and by so doing overcame much of the misogynistic prejudice against them. This was the Silver Age of Russian high culture, created by innovative poets, playwrights, theater directors, actors, dancers, and artists whose work drew international attention. A significant few of these innovators were women.

WRITERS

Some female writers of the late imperial period continued to talk about the situation of women under patriarchy, while others explored new styles in fiction and poetry. The so‑called “realists” wrote about the difficulties that female professionals experienced in the work world and also considered the lives of women in the urban middle and lower classes, as well as the peasantry. Female poets developed innovative ways of exploring women’s feelings about love and the spiritual world. Marina Tsvetaeva and Sophia Parnok were the most daring; they wrote love poetry to one another.

Women worked as journalists, editors, and publishers too. Scholars have recovered the names of 447 female journalists; undoubtedly there were many more whose articles were published without a byline.8 They wrote for all the various types of periodicals–women’s magazines, the so‑called “thick journals” read by the liberal intelligentsia, and newspapers. The situation of female journalists was similar to that of women in the other professions, that is, most held the lowest paying, least secure jobs, but there were exceptions. Alexandra Davydova edited the journal Severnyi vestnik (Northern Herald) and founded the children’s magazine Mir bozhii (God’s World). Ekaterina Kuskova and Ariadna Tyrkova were among the founders of the socialist journal Osvobozhdenie (Liberation), which they both wrote for and helped smuggle into Russia. After 1905, feminists also produced a series of periodicals.

DANCERS, SINGERS, AND ACTORS

More women than ever before were in the performing arts, and a few became international stars. Anna Pavlova is widely regarded as the greatest ballerina of the early twentieth century because of her technical skills and consummate artistry. Russia’s most popular singer was Anastasia Vialtseva, a peasant who started out in provincial theaters. “The Incomparable One” did not have a first‑class voice, but she was such a terrific performer that theater owners around the country had to hire extra security for her concerts, to prevent her fans from rioting.9

Stardom was somewhat harder for actresses to achieve, even though the Russian theater flourished in the last decades of imperial Russia. Maria Andreeva and Olga Knipper were members of the repertory company at the Moscow Art Theater, a group that invented a naturalistic style that revolutionized acting across Europe. They were well paid, while most female actors struggled to make a living. All women performers were also plagued by the public’s continuing belief that going on the stage testified to a woman’s lack of modesty and therefore probably also meant that she was sexually promiscuous. Some were; finding a well‑heeled lover was one way to survive.10

PAINTERS

It was more difficult for women to become painters, for they were not admitted to the government’s art academies. They could study at schools that trained drawing teachers and at two institutions, the Stroganov School in Moscow and the Stieglitz School in St. Petersburg, that taught the applied arts of embroidery, lace‑making, porcelain painting, jewelry‑making, and engraving. Some of the graduates of these programs then found an opening to painting careers when a rebellion against Russia’s stuffy art establishment began in the 1890s. Female painters contributed works to exhibitions sponsored by private organizations such as the Moscow Society for the Lovers of Art. They studied with the prominent painter Ilia Repin. Consequently, when the Russian avant garde developed in the 1900s, it included five women–Alexandra Ekster, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova–whose paintings, book illustrations, stage sets, costume designs, and short films broke down boundaries between artistic media and pushed beyond conventional notions of representation. Their works now hang in galleries around the world.

THE ACADEMICIANS

Throughout these decades, the intelligentsia supported women who wanted to work in fields hitherto closed to them. Its members hired female journalists, published women’s poetry, and invited female painters to submit works to art exhibits. They could not, however, alter the rules of Russia’s universities. Government officials, who had only grudgingly permitted the expansion of the higher courses for women, would not admit female graduates of those courses to advanced study or appoint women to professorial rank until after 1907.

So hundreds of women became independent scholars. We have already mentioned The Hygiene of the Female Organism, written by Varvara Kashevarova, which went through multiple editions. So did Intellectual and Moral Development of Children from the First Appearance of Consciousness to School Age, by Elizaveta Vodovozova. Still another physician, Maria Pokrovskaia, crusaded for reform in the treatment of prostitutes, publishing a book in 1902, The Medical‑Police Supervision of Prostitution Contributes to the Degeneration of the Nation. Less prominent women also labored away in their communities. In Siberia, physician and teacher Anna Bek headed local education societies and did research on childhood development. Women also joined the scientific expeditions that studied Siberia’s plants, animals, and native peoples.11

SOPHIA KOVALEVSKAIA (1850–91) AND MARIE CURIE (1867–1934)

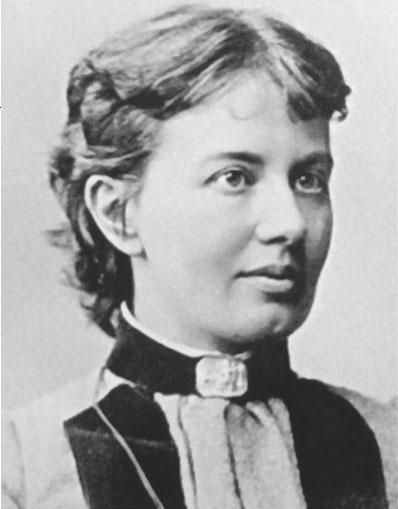

It is not surprising, in view of all this scholarly activity, that the two most accomplished female academics in Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries came from the Russian Empire. Sophia Kovalevskaia, the daughter of a liberal Polish/Russian family, was the first European woman to earn a Ph.D. in mathematics. In the 1870s, she studied in Berlin with the eminent mathematician Karl Weierstrass, who recognized her talent and persuaded his colleagues to waive the rules and grant her a doctorate. For years thereafter, Kovalevskaia applied for university positions in Russia and was turned down. Finally in 1883 she was appointed to the faculty of the University of Stockholm. Kovalevskaia wrote major papers on differential equations (one theorem still bears her name) and on the revolution of a solid body around a fixed point. By the late 1880s, she was being widely hailed as an intellectual phenomenon–Europe’s only woman professor in one of the most intellectually demanding fields, mathematics. She received the prestigious Prix Bordin in 1888 and was elected by leading academics in Russia to the Russian Academy of Sciences the following year. Still, no Russian university was permitted to hire her. Kovalevskaia was trying again to secure a professorship in her homeland when she died of an upper respiratory infection in February 1891. She is buried in Sweden, under a headstone paid for by the students of the Bestuzhev Courses.12

Marie Curie had to overcome similar obstacles. The daughter of Polish teachers in Warsaw, she enrolled in the Sorbonne in Paris in the early 1990s, and within a few years had completed her doctoral degree in physics. In collaboration with her husband Pierre Curie, she had also isolated two elements, polonium (named in tribute to Poland) and radium. Curie’s subsequent research on radium transformed the understanding of the structure of the atom and led to the development of the x‑ray as a diagnostic tool in medicine, as well as to radiation treatments for disease. The resistance at the Sorbonne to appointing her to a professorship ebbed after she was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics in 1903. Curie became the first woman to teach at that university; in 1911 she received her second Nobel Prize, this one in chemistry. Unlike Kovalevskaia, Curie did not seek to return to the Russian Empire. She became a French citizen.

Sophia Kovalevskaia in 1880.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sofja_Wassiljewna_Kowalewskaja_i.jpg. Accessed June 27, 2011.

Дата добавления: 2016-01-29; просмотров: 1084;