Shooting Across Oceans: ICBMs and Cruise Missiles

National Archives from U.S. Information Agency

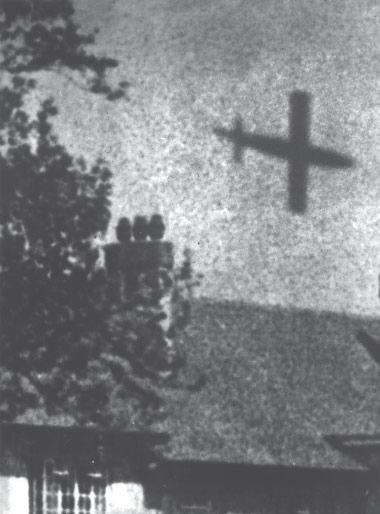

V‑1, the world’s first cruise missile, in flight over a London roof top.

On June 13, 1944, people in London heard a peculiar buzzing sound.

When they looked up, they saw a small airplane traveling across the sky at high speed. Then the plane’s engine stopped and it plunged to the ground. There was a terrific explosion. People were still wondering where the plane came from and what happened to it, when another plane just like the first appeared, and as the first did, crashed into the city and exploded. That was followed by another, then another, then several of the little planes. All crashed and exploded.

The V 1 attack had been launched.

For the first time, it was possible to bombard a target at distances beyond the range of even such hopped‑up artillery as the 1918 “Paris gun.” The German were using unpiloted planes – really flying bombs powered by pulse‑jet engines (the only time that type of engine has ever been used in combat). The Germans called the “buzz bombs” (British nickname) Vergelstungwaffe eins. To the rest of the world, the flying bomb was the V 1 – Hitler’s first “vengeance weapon.” It was also, although the name had not yet been invented, the world’s first cruise missile.

The V 1 caught the British public by surprise and inflicted heavy damage at first. The flying bombs directed at England destroyed 25,000 houses and killed 6,184 people, almost all in London. It was, however, hardly the ultimate weapon.

It had to be launched from a catapult – the only way its pulse‑jet engine could be made to start. It cruised at about 3,000 feet, easily within range of antiaircraft guns as well as fighter planes. It was fast for a plane of those days – 559 miles per hour. It was a jet, after all. But it flew in a straight line and wasn’t so fast that slightly slower (about 100 mph slower) fighter planes couldn’t shoot it down. By August 1944, Allied fighters and antiaircraft guns were shooting down 80 percent of the V 1s.

The next month, Londoners got another surprise – a nastier one than the first. The V 2s arrived. They arrived without warning. No noise announced their coming, and there was nothing to see. The first notice of their coming was a terrific explosion. The V 2 (the Germans called it the A 4) was a quantum leap ahead, technologically, of the V 1. It was a liquid‑fueled rocket with a program‑mable guidance system – a product of years of research into both space travel and weaponry. It was launched straight up, into outer space and described a high arc. Then its rocket engine stopped and it fell toward its target, powered only by gravity. That was enough to give it far more than supersonic speed, so there was no warning sound as there was with the “buzz bomb.” And it arrived so fast it was practically invisible.

The main brain behind the V 2 was a scientist named Werner von Braun, who had been fascinated by the idea of space travel as a youth and built rockets as a teenager. Von Braun, it seems, had little interest in anything but rocket technology. Politics meant nothing to him. He just wanted to build rockets.

What was done with them did not concern him. In 1932, he met an old artilleryman named Walter Dornberger. Dornberger, too, had an interest in rockets, but his reasons were different from von Braun’s. The Treaty of Versailles had forbid‑den Germany from having any heavy artillery, but it said nothing about rockets.

Dornberger saw that rockets could substitute for artillery. One result was Germany’s profusion of traditional solid‑fuel rockets like the Nebelwerfer. Braun was not particularly interested in short‑range solid fuel rockets. He had been working on liquid‑fuel rockets, using an inflammable liquid combined with liquid oxygen – a system American, Robert Goddard, had pioneered a little earlier.

Dornberger, too, was interested in long‑range rockets – at least, rockets with a longer range than the “Paris gun.” The Paris gun, the ultimate long‑range artillery piece, he said, would throw 25 pounds of high explosive 80 miles. He wanted the first rocket to throw a ton of high explosive 160 miles. But it would be a rocket that was militarily useful. It had to be accurate: it could not deviate from the target more than 2 or 3 feet for each 1,000 feet of range. And it had to be mobile: it could not be too large to transport by road.

The prototype V 2 was successfully test fired in October 1942. By the end of that year, however, British intelligence learned of the V 2 program, and the next April it learned of the Luftwaffe’s development work on a flying bomb.

Both projects were underway on the island of Peenemunde. Thereafter, the RAF bombed Peenemunde so heavily that neither weapon was ready until the summer of 1944.

By the time the V 2 was ready, the Luftwaffe V 1 batteries had been driven out of any launching site within range of England, and the V 2s never got a chance to fire from the chosen sites in France. Germany produced 35,000 V 1s, but only 9,000 were launched against England, and of these 4,000 were destroyed before they got there. The Germans continued flying buzz bombs, though. Their main target was Antwerp, the principal Allied supply base. The V 2s continued to bombard London between September 8, 1944, and March 29, 1945, when Allied troops captured their base.

While all this was going on, von Braun and other German scientists were working on a couple of projects that were really scary. Von Braun and Dornberger had written the specs for a new missile, the A 10, which would have more than one motor and would drop off each as it became exhausted. It would have a range of 2,800 miles – long enough to reach New York. At the same time, others in Germany had been working feverishly on a radically new payload: a nuclear bomb. Time ran out on the “thousand‑year Reich,” and neither project was able to help Hitler.

The ideas, of course, did not go away. One day short of three months after Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945, the United States dropped the first nuclear bomb on Hiroshima. As soon as possible, the United States brought Werner von Braun and many of his fellow rocket scientists to the United States. Russian officials brought other German scientists to the Soviet Union. Soon the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. were building ultra‑long‑range rockets and testing nuclear bombs. The super‑rockets were called Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) because, like the V 2s, when their engines stopped, they were guided by nothing but the laws of ballistics. They could not be turned back. Similar to the ICBMs are the IRBMs (Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles).

Since then, guidance systems and other features of these rockets have greatly improved. The latest intercontinental missiles have multiple warheads. The first of these were Multiple Reentry Vehicles (MRVs), which scatter warheads around a single large target to multiply the destruction. A later development was Multiple Independently‑targeted Reentry Vehicles (MIRVs). As this rocket descends, warheads and perhaps some decoys are ejected at different points to hit a number of targets. Most diabolical is the MARV system (for Maneuverable Alternative‑target Reentry Vehicle. With this system, each warhead has its own rocket, and the warheads can change course to an alternative target if anti‑ballistic missile defenses appear.

At present, all of these ICBMs are designed for nuclear warheads. They are far too expensive to waste on mere high‑explosive warheads. None of them have ever been used. And the world hopes, they may never be used. All wars and all foreign policy, however, have been conducted with fear of the nuclear‑armed ICBM in the background influencing every decision.

Superpowers and even great powers refuse to be stymied because they can’t use the long‑range nukes. They do avoid conflict with each other because of the nuclear danger, and they do not even use their nukes on small powers for fear that such action might provoke others to use nuclear weapons. They do, however, use long‑range missiles. These missiles, carrying high explosive warheads are much cheaper than ICBMs. They are a development of the old V 1.

Cruise missiles were a major U.S. weapon in both the Gulf War of 1991 and the Iraq War of 2002. There were two types: the Tomahawk and the CALCM (for Conventional Air Launched Cruise Missile). In both wars, the Tomahawk was launched from both surface ships and submarines. Some subs are equipped to launch the missiles through the deck the same way the Polaris ballistic missiles are, others are merely shoot out of the torpedo tubes, after which they rise to the surface and fly away. The CALCMs are launched from B 52 bombers.

They have less range than the Tomahawks, because their launching vehicles can get closer to most targets, but they carry a bigger warhead.

In one way the modern cruise missiles are similar to their V 1 ancestor.

They’re also powered by jet engines (turbofan jets in this case), and they both have a maximum speed of around 590 miles per hour. Their range and accuracy has vastly improved, though. The Tomahawk can travel 1,550 miles and, even at maximum range, it can hit “within meters” of its target. Tomahawks in the Gulf War were guided by a radar system which noted terrain features of the land it was flying over and electronically compared them with topographical information programmed into it. In the Gulf War, this was largely replaced by a global positioning satellite system that was even more accurate.

Tomahawks were the weapon of choice not only in the two Mesopotamian conflicts but in such other situations as during the Clinton administration when U.S. Navy cruise missiles flattened a Sudanese chemical plant that was believed to be producing nerve gas for Al Qaeda and some public buildings in Baghdad in reprisal for an attempt to assassinate former president George H. W. Bush.

Long‑range missiles, even without nuclear warheads have changed modern warfare considerably.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1203;