David as a Tin Fish: The Modern Torpedo

National Archives from War Department

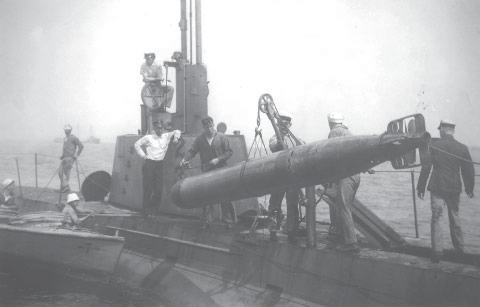

Torpedo being loaded aboard a U.S. submarine in 1918.

Not all torpedoes in the American Civil War were like those Farragut had damned (see Chapter 23). They didn’t all lie in wait for a ship to hit them.

There were two kinds that went after their prey. One was the spar torpedo, an explosive charge on the end of a long pole. The pole was attached to the bow of a small, fast surface vessel or a submarine. The attacker either rammed the torpedo into its prey, setting off the explosive, or it poked the torpedo under the enemy hull, then detonated it by pulling a string that released a firing pin.

The second type was the towed torpedo. This was dragged through the water by a small fast boat that cut across the path of an enemy ship. The enemy ship hit the tow rope and dragged the torpedo against itself.

Some pirates in the South China Sea use a similar method. Two pirate boats connected by a cable straddle the path of a freighter during the night when most of the ship’s crew can be expected to be asleep. The ship hits the cable and drags the two pirate boats against itself. The pirates then climb aboard and take over the ship.

This scenario indicates one of the problems in the use of the towed torpedo: What happens to the boat that was towing the torpedo? If the enemy did not hit the rope at the right spot, the tow boat would be slammed against the side of the enemy ship before the torpedo. The problem with both types of torpedo was that ideally they should be used by crews with suicidal tendencies. When the C.S.S. Hunley, a Confederate submarine, sank the U.S.S. Housatonic in the Civil War (the first time a submarine ever sank another ship) with a spar torpedo, Hunley sank herself.

In 1866, in what is now Trieste, Italy, but was then part of Austria, an Austrian naval captain named Luppis considered these problems. How could he make a torpedo that did not require a crew of Kamakazes? He consulted a Scottish engineer named Robert Whitehead, who was living in that part of Austria. Together, they devised a miniature unmanned submarine that carried an explosive charge, or “warhead,” in its nose. Whitehead later made further improvements to the weapon and set up a company to manufacture “locomotive torpedoes,” as they were called. He finally sold the company to Vickers, the British armaments giant.

Whitehead and Vickers managed to sell quite a few torpedoes although the early Whitehead torpedoes were not all that impressive. They carried a mere 18 pounds of explosive, traveled at a speed of six knots and had a maximum range of 370 yards. Furthermore, they lacked reliable control of direction and depth‑keeping. Progress was rapid, however. By 1876, Whitehead torpedoes had a range of 600 yards; by 1905, they had a range of 2,190 yards. The next year, 1906, the range had jumped to 6,560 yards. By 1913, the year before World War II, the torpedo could travel 18,590 yards. Speed and control improved at the same rate as range. By World War II, the Japanese “Long Lance” torpedo – by far the best torpedo in the war – had a range of 11 miles at a speed of 49 knots while carrying a 1,000 pound warhead.

Even the primitive torpedoes gave the world’s battleship admirals a fright.

Battleships in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were the most expensive of all war machines. Compared to them, the cost of a torpedo was negligible, but one torpedo could sink the most expensive battleship. The battleship was Goliath – huge, powerful, and fearsome – but the torpedo was David. The short range and inaccuracy of the early torpedoes was no consolation to the naval powers‑that‑be. Small fast steam launches, whose cost was also negligible compared to battleships, could race up to battleships and release their torpedoes at ranges so short they couldn’t miss. The guns of most battleships, particularly those of Britain, the world’s premiere naval power, probably wouldn’t be able to stop the little boats. France, Britain’s ancient rival, decided to concentrate on building torpedo boats and commerce raiders to neutralize British control of the seas.

An ambitious and imaginative British naval officer, Captain John Arbuthnot

“Jacky” Fisher, began a campaign that radically changed the armaments of the Royal Navy and, consequently, that of all the world’s navies.

British battleships in 1880 were comparatively heavily armored and slow.

Their ponderous wrought‑iron guns were muzzle‑loaders – a few accidents with early breech‑loaders having convinced the Royal Navy that muzzle‑loading was safer. Muzzle‑loading the huge guns now needed on battleships required a complicated arrangement of cranes and was slower than breech‑loading.

The first attempt to cope with the torpedo boat threat was to add very heavy machine guns to the ships’ armament. Gatling and Nordenfelt mechanical machine guns in calibers of an inch or more appeared on ships. The Hotchkiss revolver cannon – a multi‑barrel gun that threw a 37 mm explosive shell – became popular with the world’s navies. Then Maxim introduced its one‑pounder automatic cannon, the famous “pom‑pom,” but, as the range and speed of torpedoes increased, these light cannons were no longer adequate. The British began purchasing steel breech‑loaders capable of firing a 6‑pound shell 12 times a minute with a three‑man crew. Steel artillery and breech‑loading had been pioneered by continental firms like Krupp in Germany and Hotchkiss in France.

Breech‑loading mechanisms were far safer than the early ones, and steel was far stronger than wrought iron. The new guns let more powerful ammunition be fired more quickly. Torpedoes, though, were improving at least as fast as guns.

Something more was needed.

In 1886, Jacky Fisher, now director of naval ordnance, was authorized to get guns from private corporations instead of the royal arsenal. Armstrong, with Vickers, the second British armaments giant, had just what he was looking for – steel breech‑loaders that took a 6‑inch shell and had a new, French‑developed recoil mechanism that absorbed the recoil and returned the gun to its point of aim. (See Chapter 28 on quick‑firing artillery.) About the only limitation on its speed of fire was the strength of the gun crew. The breech‑loading and recoil systems could be applied to big guns, too, making possible smaller turrets and quicker, more accurate fire. The modern battleship was born, and all navies that didn’t have such ships began to copy the British.

Fisher, an early torpedo enthusiast, still wasn’t satisfied that battleships were adequately protected from torpedo boats. As a rear admiral and third sea lord in the British admiralty, he got the navy to change to a new type of steam boiler that greatly improved the power of its engines. Then he introduced a new fast ship, smaller than a cruiser but bigger, faster, and more heavily armed than a torpedo boat. It was called a “torpedo boat destroyer,” and that was its mission. Today, its name shortened to destroyer and with different missions, it is still a staple of all navies. Fisher also pushed for more and better submarines, but, although he eventually became first sea lord (the top officer in the Royal Navy), he could not totally overcome the opposition of other naval brass who hated the thought of submarines, which they saw as the greatest threat to the surface fleet. The British did adopt the submarine, but built only a few.

In both world wars, the submarine, whose main weapon was the torpedo, proved to be the most efficient user of those miniature submarines sailors call “tin fish.” (See Chapter 29.) Airplanes were a close second.

Surprisingly, in World War II, the United States, the country with the largest, and in most ways, most modern, navy, had the worst torpedoes. Admiral Samuel Morison, the official navy historian of World War II, attributed the deficiency to a combination of poor design, obsolescence, false economy and inefficiency at the navy‑owned torpedo factory in Newport, Rhode Island. Most of the torpedoes were left over from World War I. The detonators sometimes failed to work even if the target was hit squarely, and too often the target was not hit because the depth regulator was faulty. Submarine commanders returned from patrol reporting they had heard as many as nine torpedoes strike a Japanese ship without exploding.

The U.S. Navy was convinced that the next war’s naval battles would be fought at long range with big guns, so it took the torpedo tubes off its cruisers.

The torpedo, in spite of the phenomenal Japanese “Long Lance,” was essentially a short‑range weapon. And to much of the naval brass, and an even higher proportion of Congress, battleships and aircraft carriers were glamor weapons – not destroyers and submarines.

By mid‑1943, however, American torpedo troubles had been cured, and U.S. submarines proceeded to sink most of Japan’s cargo fleet and a high proportion of its navy with torpedoes. (See Chapter 29.) Torpedoes appeared in a wide variety of forms during the two world wars.

Most, as with the original Whitehead torpedo, were powered by a miniature steam engine using compressed air or oxygen to allow combustion. The steam engine provide great speed and long range, but it left a visible wake, giving target ships a chance to evade the missile. The Germans introduced a torpedo with an electric engine that left no wake, but it was slow and short‑ranged.

Later the Americans captured one and improved it, producing a faster, longer‑ranged torpedo that still left no wake. The Japanese, not satisfied with their Long Lance, developed a special torpedo for use at Pearl Harbor, a location considered unsuitable for aerial torpedoes because of the constricted space and shallow water. The new torpedo traveled fairly close to the surface and armed itself almost immediately after it was dropped. Another German innovation was an acoustic torpedo that homed in on the noise of a ship’s engines and propellers. The Allies foiled this with the “Foxer,” a device towed by a ship that produced noises that made the acoustic torpedo hit the decoy. The United States also produced a homing torpedo and used it as an anti‑submarine weapon. “Fido,” it was called, because it “smelled” its prey in deep water. When it saw a U.S. plane approaching, an enemy submarine invariably dived. When that happened, the plane dropped Fido, which pursued the now invisible sub and sank it.

A post‑war torpedo guidance system uses active acoustic homing. The torpedo sends out sounds, like a sonar system does, to locate a submarine lying motionless on the sea bottom, then homes in on the target. Another type of torpedo is steered by signals reaching it over a long, thin wire. Wire guidance is not really new. The Brennan torpedo, a 19th‑century rival of the Whitehead, used wire guidance. Wire technology at that time was primitive, however, and the wire was thick. The Brennan torpedo required a mass of wire so large it was inconvenient and even dangerous aboard a ship. The wire‑guided torpedo had to wait another half‑century.

With all its forms and ways of delivery – surface vessel, submarine, or aircraft – the torpedo has thoroughly changed naval warfare, and it may bring more changes in the future.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1357;