The First Warship: The Galley

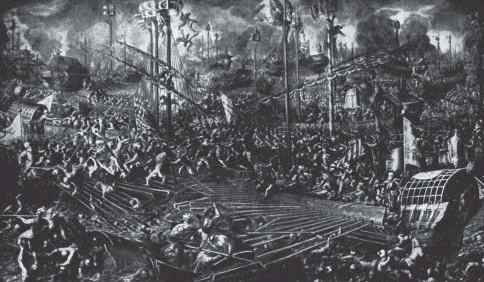

Galleys clash at Lepanto, the last major battle fought with these craft.

On September 13, 1569, the gunpowder factory at the Venetian Arsenal exploded. The Arsenal was the center of all Venetian military power. The gunpowder factory was only one part of it. Guns were cast there, warships were built there, galleys were docked there, and all kinds of weapons were stored there. Venice was one of the two great powers of the eastern Mediterranean.

But the explosion, it seemed, had instantly rendered the republic helpless.

That blast was a disaster for Venice, but for the other great power of the eastern Mediterranean, it sounded like the knock of opportunity. Turkey, under its aptly nicknamed Sultan, Selim the Sot, began gobbling up outposts of the Venetian Empire. The Christian powers united in the face of the Turkish threat and assembled a fleet of warships. In addition to the ships Venice still had there were galleys from the Papal States, Austria, Naples, Sicily, and, especially, Spain. King Philip II of Spain used the gold and silver he got from his American colonies to pay half the costs of the entire expedition. Then he made his young half‑brother, Don Juan of Austria, commander of the fleet.

Don Juan reorganized the Christian fleet. To eliminate national rivalries, with a consequent failure to coordinate with each other, he mixed the nationalities in the three divisions of his fleet. Augustino Barbarigo, a Venetian admiral, commanded the left. Giovanni Andrea Doria of Genoa commanded the right.

Don Juan led the center, with the 75‑year‑old Doge of Venice, Sebasitiano Veniero, commanding the galley on the left of his flagship and Marco Antonio Colonna, the Papal admiral, commanding the ship on the right. Almost all of the ships in Don Juan’s fleet were galleys, the traditional Mediterranean warships. Galleys, the long, narrow, oar‑propelled warships, had dominated the Inland Sea for three millennia. Don Juan added two less traditional ships: galleasses. Galleasses were sailing ships with a high freeboard. They could use oars in a pinch, but they were slow and clumsy when rowed. Don Juan knew that the Portuguese had used similar high‑freeboard sailing ships successfully in combat on the Indian Ocean. He thought there might be a place for them in this battle. Though slower and far less agile than the galleys, they had two advantages: their sides were too high for a galley’s crew to board them easily, and they had many guns.

In ancient times, galleys had used bronze rams on their bows to crush the sides of opposing ships. Because cannons had been invented, they replaced the ram. The Turkish galleys had three cannons firing over their bows. The Christian ships had four.

The enemy fleets met in the Gulf of Corinth, the long, narrow bay that almost cuts Greece in two, near the town of Lepanto. In battle, galleys were handled as if they were soldiers in a land battle. They charged each other directly, blasting the enemy with their bow guns. Because their sides were lined with rowers and their sterns occupied by steersmen with huge steering oars, there was no other place for the guns. Like armies, galley fleets attempted to break through an enemy’s line, or attack his flanks, or encircle him. The Christians may have had more guns, but the Turks had more ships. To avoid being flanked, Andrea Doria advanced obliquely to the right, so his division made contact later than the rest of Don Juan’s fleet. The Turkish admiral commanding the Muslim right, Mohammed Sirocco Pasha, tried to encircle the Christian left. Barbarigo, unfamiliar with the waters, had stayed well off shore. When he saw Sirocco’s ships trying to flank him, though, Barbarigo knew the water was deep enough. He had his ships swivel and charge, catching the Turkish column in the flank and rear. Barbarigo was killed. His nephew succeeded him in command but was killed almost immediately afterwards. But two other Venetian officers, Frederigo Nani and Marco Quirini, took over. They drove the Turks ashore and killed or captured them all.

In the center, Don Juan’s galleasses demonstrated their worth. Their gunfire raised havoc with the Turkish galleys. The Turks saw that they were too high to board and rowed furiously away from them, disrupting their own formation. Then Don Juan and the Turkish commander‑in‑chief, Ali Pasha, exchanged salutes and closed with each other. In spite of the superior Christian gunnery, Ali drove his galley right up to Don Juan’s while soldiers on the decks of both ships showered each other with arrows and musket bullets. The Turks boarded the Spanish ship, but were pushed off, and the Spanish boarded the Turkish ship. The Turks pushed the Spaniards back to their ship and followed them, only to be again pushed off and boarded again. Veniero, the Doge, and his men joined the melee. Ali was killed and his ship taken. Meanwhile, Colonna, on the other side of the flagship, burned a Turkish galley. The center division began taking or sinking Turkish galleys all along the line. The remaining Turks reversed their ships and fled.

Uluch Ali, the commander of the Turkish left, had been trying unsuccessfully to flank Andrea Doria. He suddenly changed course and darted through the gap between the Christian center and right. He managed to get behind Don Juan’s formation, but the Spanish admiral cut loose the prizes he had been towing and turned toward Uluch Ali’s unit. Caught between Don Juan and the Christian reserve, Uluch Ali fled to the nearest Turkish harbor. Some of his ships made it.

Lepanto was the greatest defeat the Turks had ever suffered in the Mediterranean. Selim the Sot built a new fleet, but his ships were built of green wood and manned by greener sailors. From then on the Turkish Navy studiously sought to avoid battle. The Turks would still threaten Christendom, but after Lepanto, they were a greatly diminishing threat. That’s one reason Lepanto is a notable battle.

The other reason is that it was the last great battle between galleys. Don Juan’s four‑gun galleys were not the wave of the future; his big, clumsy, heavily gunned galleasses were. That had been demonstrated more than 60 years earlier when a handful of Portuguese sailing ships wiped out 200 Turkish and Egyptian galleys off the Indian port of Diu. (See Chapter 13, The Sailing Man of War.) After Lepanto, the galley would never again play an important part in naval warfare, but it had had a long and honorable career.

As did the spear and the bow, the origins of the galley are lost in the mists of prehistory. The first boats were probably dugout canoes, propelled by paddles.

They were followed by lighter boats with a covering of leather or bark stretched over a framework of wood. Someone discovered that rowing provided more powerful propulsion than paddling, and, probably about the same time, someone learned that fixing a sail to the boat made rowing unnecessary if the wind was right. From there, developing the galley was merely a matter of making a bigger row‑or‑sail boat with wooden sides.

One of the earliest accounts of a galley and its crew is the legend of Jason and the Argonauts, who sailed from Greece to Colchis on the Black Sea in search of the Golden Fleece. According to the legend, the expedition took place a generation before the Trojan War. To see if Jason’s voyage was even possible, Tim Severin, the adventurer who crossed the North Atlantic in a skin boat to retrace the legendary voyage of St. Brendan, the Irish monk who supposedly reached America in the Dark Ages, built a replica of Jason’s galley, Argo. Severin consulted experts on ancient Greek shipping and had a galley built according to the ship‑building methods of Jason’s time. The craft was 52 feet long and seated 20 rowers. It took Severin and his crew from Greece to the site of ancient Colchis. The crew was even able to row against a head wind added to the ferocious currents of the Bosporus that have defeated many modern boats. All the modern Argonauts agreed, however, that sailing on that sort of ancient galley was no holiday.

As time went on, ancient ship builders improved their designs. The boat had to be light, so it could be rowed swiftly, but it had to be strong enough to be seaworthy. It had to be fairly low so the rowers could use their oars at the optimum angle. Before long, ship builders were using mathematical formulae.

Within reason, the longer the ship, the faster it would be, but the ship should not be longer than 10 times its beam or it would be too fragile to take to sea. In his Greek and Roman Naval Warfare, Admiral W.L. Rodgers explains the many calculations the ancient ship builders had to make. Ships got bigger and got two or three rows of oars. They got still bigger and had two or three men on each oar, sometimes as many as five men on each oar. According to Rodgers, a small Greek trireme of the Peloponnesian War period would carry about 18 soldiers for boarding, about 162 rowers, and 20 more as officers, row masters, and seamen. All the rowers were free men (not slaves, as they were during renaissance times), and all had weapons and took part in any melee when their ship was boarded. The galley would be 105 feet long, displace 69 tons, and be capable of 7.8 knots (almost 9 mph) at top speed.

Galleys were extremely maneuverable. With the rowers on one side pulling normally and those on the other side backing water, the galley could almost swivel on the spot. Oars were arranged so the rowers could step over them and back up instantly. Rapid maneuvering was essential, because a galley captain aimed to ram the side of an enemy vessel while avoiding being rammed himself.

Another favorite tactic in galley fighting was to brush close to an enemy’s side, pulling your oars out of the way at the last minute. The intention was to catch the enemy’s oars still in rowing position and break them off. Galley crews threw fire pots on enemy ships to burn them, tossed jars of soft soap to make enemy decks slippery, and sometimes threw jars of poisonous snakes to distract enemy crews.

In Hellenistic and Roman times, galleys, which had grown quite large, were often equipped with catapults to hurl such missiles. And in the 7th century, the Eastern Romans came up with the ultimate weapon in galley warfare: Greek fire. That’s worth a separate chapter (see Chapter 8).

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1230;