The sweet smell

THE CHANGES THAT HAVE swept through Greeley, Colorado, have also occurred throughout the High Plains, wherever large meatpacking plants operate. Towns like Garden City, Kansas, Grand Island, Nebraska, and Storm Lake, Iowa, now have their own rural ghettos, drugs, poverty, rootlessness, and crime. Some of the most dramatic changes have occurred in Lexington, Nebraska, a small town about three hours west of Omaha. Lexington looks like the sort of place that Norman Rockwell liked to paint: shade trees, picket fences, modest Victorian homes, comfy chairs on front porches. The appearance is deceiving.

In 1990, IBP opened a slaughterhouse in Lexington. A year later, the town, with a population of roughly seven thousand, had the highest crime rate in the state of Nebraska. Within a decade, the number of serious crimes doubled; the number of Medicaid cases nearly doubled; Lexington became a major distribution center for illegal drugs; gang members appeared in town and committed drive‑by shootings; the majority of Lexington’s white inhabitants moved elsewhere; and the proportion of Latino inhabitants increased more than tenfold, climbing to over 50 percent. “Mexington” – as it is now called, affectionately by some, disparagingly by others – is an entirely new kind of American town, one that has been transfigured to meet the needs of a modern slaughterhouse. You would never think, driving past the IBP plant in Lexington, with its colorful children’s playground out front, with Wal‑Mart and Burger King across the street, that a single, innocuous‑looking building could be responsible for so much sudden change, hardship, and despair.

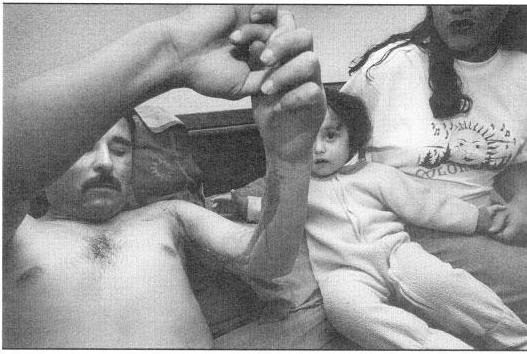

In Lexington I met a cross‑section of IBP workers. I met Guatemalan Indians who spoke no English and barely spoke Spanish, living in a dark basement strewn with garbage and used diapers. I met Mexican farm workers struggling to get used to the long Nebraska winters. I met one IBP worker who’d recently been a housekeeper in Santa Monica and another whose previous job was collecting manure from fields in rural Mexico and selling it as fertilizer. I met hard‑working, illiterate, religious people willing to risk injury and endure pain for the benefit of their families.

The smell that permeates Lexington is even worse than the smell of Greeley. “We have three odors,” a Lexington resident told a reporter: “burning hair and blood, that greasy smell, and the odor of rotten eggs.” Hydrogen sulfide is the gas responsible for the rotten egg smell. It rises from slaughterhouse wastewater lagoons, causes respiratory problems and headaches, and at high levels can cause permanent damage to the nervous system. In January of 2000, the Justice Department sued IBP for violations of the Clean Air Act at its Dakota City plant, where as much as a ton of hydrogen sulfide was being released into the air every day. As part of a consent decree, IBP agreed to cover its wastewater lagoons there. “This agreement means that Nebraskans will no longer be forced to inhale IBP’s toxic emissions,” said a Justice Department official. As of this writing, IBP is also preparing to cover its Lexington wastewater lagoons.

On July 7, 1988, IBP held a public forum at a junior high school in Lexington, giving local citizens an opportunity to ask questions about the company’s proposal to build a slaughterhouse there. The transcript of this meeting says a lot about how IBP views the rural communities where it operates. Would there be much turnover among workers at the new IBP plant, someone asked. Once the slaughterhouse was running, an IBP executive replied, it would have a stable workforce. “Ninety percent of our people,” he said, “or 80 percent will be fairly stable.” Would local people be hired for these jobs, someone else asked. “We will not bring in an hourly workforce,” the IBP executive promised. A local IBP booster, who had just returned from a visit to the company’s slaughterhouse in Emporia, Kansas, suggested there was little reason to worry about the “type of people” the plant might attract or the potential for increased crime. He said that in Emporia, apparently, “they work them so hard at IBP that they’re tired and they go home and go to bed.” An IBP executive, a vice president of public relations, confirmed that assessment. “And people who work on our lines work hard,” he told the gathering. “As the chief of police [in Emporia] said, they go home at night and go to bed rather than carouse around town.” Another IBP executive, a vice president of engineering, assured the audience that the new plant in Lexington would not foul the air. No odor would be noticeable, he promised, even “a few feet away” from the plant. In any event, the smell emitted by slaughterhouse lagoons would be “sweet,” not objectionable. And the smell from the slaughterhouse itself, the IBP vice president said, would be “no different than that which you produce in your kitchen when you cook.”

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1038;