JUST A HEAD

Decapitation, Reanimation, and the Human Head Transplant

If you really wanted to know for sure that the human soul resides in the brain, you could cut off a man’s head and ask it. You would have to ask quickly, for the human brain cut off from its blood supply will slide into unconsciousness after ten or twelve seconds. You would, further, have to instruct the man to answer with blinks, for, having been divorced from his lungs, he can pull no air through his larynx and thus can no longer speak. But it could be done. And if the man seemed more or less the same individual he was before you cut off his head, perhaps a little less calm, then you would know that indeed the self is there in the brain.

In Paris, in 1795, an experiment very much like this was nearly undertaken. Four years before, the guillotine had replaced the noose as the executioner’s official tool. The device was named after Dr. Joseph Ignace Guillotin, though he did not invent it. He merely lobbied for its use, on the grounds that the decapitating machine, as he preferred to call it, was an instantaneous, and thus more humane, way to kill.

And then he read this:

Do you know that it is not at all certain when a head is severed from the body by the guillotine that the feelings, personality and ego are instantaneously abolished…? Don’t you know that the seat of the feelings and appreciation is in the brain, that this seat of consciousness can continue to operate even when the circulation of the blood is cut off from the brain…? Thus, for as long as the brain retains its vital force the victim is aware of his existence. Remember that Haller insists that a head, having been removed from the shoulders of a man, grimaced horribly when a surgeon who was present stuck a finger into the rachidian canal…. Furthermore, credible witnesses have assured me that they have seen the teeth grind after the head has been separated from the trunk. And I am convinced that if the air could still circulate through the organs of the voice… these heads would speak….

…The guillotine is a terrible torture! We must return to hanging.

It was a letter, published in the November 9, 1795, Paris Moniteur (and reprinted in André Soubiran’s biography of Guillotin), written by the well‑respected German anatomist S. T. Sömmering. Guillotin was horrified, the Paris medical community atwitter. Jean‑Joseph Sue, the librarian at the Paris School of Medicine, came out in agreement with Sömmering, declaring his belief that the heads could see hear, smell, see, and think. He tried to convince his colleagues to undertake an experiment whereby “before the butchery of the victim,” a few of the unfortunate’s friends would arrange a code of eyelid or jaw movements which the head could use after the execution to indicate whether it was “fully conscious of [its] agony.” Sue’s colleagues in the medical community dismissed his idea as ghastly and absurd, and the experiment was not carried out. Nonetheless, the notion of the living head had made its way into the public consciousness and even popular literature. Below is a conversation between a pair of fictional executioners, in Alexandre Dumas’s Mille et Un Phantomes :

“Do you believe they’re dead because they’ve been guillotined?”

“Undoubtedly!”

“Well, one can see that you don’t look in the basket when they are all there together. You’ve never seen them twist their eyes and grind their teeth for a good five minutes after the execution. We are forced to change the basket every three months because they cause such damage to the bottom.”

Shortly after Sömmering’s and Sue’s pronouncements, Georges Martin, an assistant to the official Paris executioner and witness to some 120 beheadings, was interviewed on the subject of the heads and their post‑execution activities. Soubiran writes that he cast his lot (not surprisingly) on the side of instantaneous death. He claimed to have viewed all 120 heads within two seconds and always “the eyes were fixed…. The immobility of the lids was total. The lips were already white….” Medical science was, for the moment, reassured, and the furor dissipated.

But French science was not through with heads. A physiologist named Legallois surmised in an 1812 paper that if the personality did indeed reside in the brain, it should be possible to revive une tête séparée du tronc by giving it an injection of oxygenated blood through its severed cerebral arteries. “If a physiologist attempted this experiment on the head of a guillotined man a few instants after death,” wrote Legallois’s colleague Professor Vulpian, “he would perhaps bear witness to a terrible sight.”

Theoretically, for as long as the blood supply lasted, the head would be able to think, hear, see, smell (grind its teeth, twist its eyes, chew up the lab table), for all the nerves above the neck would still be intact and attached to the organs and muscles of the head. The head wouldn’t be able to speak, owing to the aforementioned disabling of the larynx, but this was probably, from the perspective of the experimenter, just as well.

Legallois lacked either the resources or the intestinal fortitude to follow through with the actual experiment, but other researchers did not.

In 1857, the French physician Brown‑Séquard cut the head off a dog (“Je décapitai un chien…” ) to see if he could put it back in action with arterial injections of oxygenated blood. Eight minutes after the head parted company with the neck, the injections began. Two or three minutes later, Brown‑Séquard noted movements of the eyes and facial muscles that appeared to him to be voluntarily directed. Clearly something was going on in the animal’s brain.

With the steady supply of guillotined heads in Paris, it was only a matter of time before someone tried this out on a human. There could be only one man for the job, a man who would more than once make a name for himself (lots of names, probably) by doing peculiar things to bodies with the aim of resuscitating them. The man for the job was Jean Baptiste Vincent Laborde, the very same Jean Baptiste Vincent Laborde who appeared earlier in these pages advocating prolonged tongue‑pulling as a means of reviving the comatose, mistaken‑for‑dead patient. In 1884, the French authorities began supplying Laborde with the heads of guillotined prisoners so that he could examine the state of their brain and nervous system. (Reports of these experiments appeared in various French medical journals, Revue Scientifique being the main one.) It was hoped that Laborde would get to the bottom of what he called la terrible legende –that it was possible for guillotined heads to be aware, if only for a moment, of their situation (in a basket, without a body). Upon a head’s arrival in his lab, he would quickly bore holes in the skull and insert needles into the brain in an attempt to trigger nervous system responses.

Following Brown‑Séquard’s lead, he also tried resuscitating the heads with a supply of blood.

Laborde’s first subject was a murderer named Campi. From Laborde’s description, he was not a typical thug. He had delicate ankles and white, well‑manicured hands. His skin was unblemished save for an abrasion on the left cheek, which Laborde surmised was the result of the head’s drop into the guillotine basket. Laborde didn’t typically spend so much time personalizing his subjects, preferring to call them simply restes frais . The term means, literally, “fresh remains,” though in French it has a pleasant culinary lilt, like something you might order off the specials board at the neighborhood bistro.

Campi arrived in two pieces, and he arrived late. Under ideal circumstances, the distance from the scaffold to Laborde’s lab on Rue Vauquelin could be covered in about seven minutes. Campi’s commute took an hour and twenty minutes, owing to what Laborde called “that stupid law” forbidding scientists to take possession of the remains of executed criminals until the bodies had crossed the threshold of the city cemetery. This meant Laborde’s driver had to follow the heads as they “made the sentimental journey to the turnip field” (if my French serves) and then pack them up and bring them all the way back across town to the lab. Needless to say, Campi’s brain had long since ceased to function in anything close to a normal state.

Infuriated by the waste of eighty critical postmortem minutes, Laborde decided to meet his next head at the cemetery gates and set directly to work on it. He and his assistants rigged a makeshift traveling laboratory in the back of a horse‑drawn van, complete with lab table, five stools, candles, and the necessary equipment. The second subject was named Gamahut, a fact unlikely to be forgotten, owing to the man’s having had his name tattooed on his torso. Eerily, as though presaging his gory fate, he had also been tattooed with a portrait of himself from the neck up, which, without the lines of a frame to suggest an unseen body, gave him the appearance of a floating head.

Within minutes of its arrival in the van, Gamahut’s head was installed in a styptic‑lined container and the men set to work, drilling holes in the skull and inserting needles into various regions of the brain to see if they could coax any activity out of the criminal’s moribund nervous system.

The ability to perform brain surgery while traveling full tilt on a cobblestone street is a testament to the steadiness of Laborde’s hand and/or the craftsmanship of nineteenth‑century broughams. Had the vehicle’s manufacturers known, they might have crafted a persuasive ad campaign, à la the diamond cutter in the backseat of the smooth‑riding Oldsmobile.

Laborde’s team ran current through the needles, and the Gamahut head could be seen to make the predictable twitches of lip and jaw. At one point–to the astonished shouts of all present–the prisoner slowly opened one eye, as if, with great and understandable trepidation, he sought to figure out where he was and what sort of strange locality hell had turned out to be. But, of course, given the amount of time that had elapsed, the movement could have been nothing beyond a primitive reflex.

The third time around, Laborde resorted to basic bribery to expedite his head deliveries. With the help of the local municipality chief, the third head, that of a man named Gagny, was delivered to his lab just shy of seven minutes after the chop. The arteries on the right side of the neck were injected with oxygenated cow’s blood, and, in a break from BrownSéquard’s protocol, the arteries on the other side were connected to those of a living animal: un chien vigoureux . Laborde had an arresting flair for details, which the medical journals of his day seemed pleased to accommodate. He devoted a full paragraph to an artful description of a severed head resting upright on the lab table, rocking ever so slightly left and right from the pulsing pressure of the dog’s blood as it pumped into the head. In another paper, he took pains to detail the postmortem contents of Gamahut’s excretory organs, though the information bore no relation to the experiment at hand, noting with seeming fascination that the stomach and intestines were completely empty save for un petit bouchon fécal at the far end.

With the Gagny head, Laborde came closest to restoring normal brain function. Muscles on the eyelids, forehead, and jaw could be made to contract. At one point Gagny’s jaw snapped shut so forcefully that a loud claquement dentaire was heard. However, given that twenty minutes had passed from the drop of the blade to the infusion of blood–and irreversible brain death sets in after six to ten minutes–it is certain that Gagny’s brain was too far gone to be brought around to anything resembling consciousness and he remained blessedly ignorant of his dismaying state of affairs. The chien , on the other hand, spent its final, decidedly less vigoureux minutes watching its blood pump into someone else’s head and no doubt produced some claquements dentaires of its own.

Laborde soon lost interest in heads, but a team of French experimenters named Hayem and Barrier took up where he left off. The two became something of a cottage industry, transfusing a total of twenty‑two dog heads, using blood from live horses and dogs. They built a tabletop guillotine specially fitted to the canine neck and published papers on the three phases of neurological activity following decapitation. Monsieur Guillotin would have been deeply chagrined to read the concluding statements in Hayem and Barrier’s description of the initial, or “convulsive,” postdecapitation phase. The physiognomy of the head, they wrote, expresses surprise or ” une grande anxiété ,” and appears to be conscious of the exterior world for three or four seconds.

Eighteen years later, a French physician by the name of Beaurieux confirmed Hayem and Barriers observations–and Sömmering’s suspicions. Using Paris’s public scaffold as his lab, he carried out a series of simple observations and experiments on the head of a prisoner named Languille, the instant after the guillotine blade dropped.

Here, then, is what I was able to note immediately after the decapitation: the eyelids and lips of the guillotined man worked in irregularly rhythmic contractions for about five or six seconds… [and] ceased. The face relaxed, the lids half closed on the eyeballs, …exactly as in the dying whom we have occasion to see every day in the exercise of our profession…. It was then that I called in a strong, sharp voice, “Languille!” I then saw the eyelids slowly lift up, without any spasmodic contraction… such as happens in everyday life, with people awakened or torn from their thoughts. Next Languille’s eyes very definitely fixed themselves on mine and the pupils focused themselves. I was not, then, dealing with the sort of vague dull look without any expression that can be observed any day in dying people to whom one speaks. I was dealing with undeniably living eyes which were looking at me.

After several seconds, the eyelids closed again, slowly and evenly, and the head took on the same appearance as it had had before I called out. It was at that point that I called out again, and, once more, without any spasm, slowly, the eyelids lifted and undeniably living eyes fixed themselves on mine with perhaps even more penetration than the first time…. I attempted the effect of a third call; there was no further movement–and the eyes took on the glazed look which they have in the dead….

You know, of course, where this is leading. It is leading toward human head transplants. If a brain–a personality–and its surrounding head can be kept functional with an outside blood supply for as long as that supply lasts, then why not go the whole hog and actually transplant it onto a living, breathing body, so that it has an ongoing blood supply?

Here the pages fly from the calendar and the globe spins on its stand, and we find ourselves in St. Louis, Missouri, May 1908.

Charles Guthrie was a pioneer in the field of organ transplantation. He and a colleague, Alexis Carrel, were the first to master the art of anastomosis: the stitching of one vessel to another without leaks. In those days, the task required great patience and dexterity, and very thin thread (at one point, Guthrie tried sewing with human hair). Having mastered the skill, Guthrie and Carrel went anastomosis‑happy, transplanting pieces of dog thighs and entire forelimbs, keeping extra kidneys alive outside of bodies and stitching them into groins. Carrel went on to win the Nobel Prize for his contributions to medicine; Guthrie, the meeker and humbler of the two, was rudely overlooked.

On May 21, Guthrie succeeded in grafting one dog’s head onto the side of another’s neck, creating the world’s first man‑made two‑headed dog. The arteries were grafted together such that the blood of the intact dog flowed through the head of the decapitated dog and then back into the intact dog’s neck, where it proceeded to the brain and back into circulation. Guthrie’s book Blood Vessel Surgery and Its Applications includes a photograph of the historic creature. Were it not for the caption, the photo would seem to be of some rare form of marsupial dog, with a large baby’s head protruding from a pouch in its mother’s fur. The transplanted head was sewn on at the base of the neck, upside down, so that the two dogs are chin to chin, giving an impression of intimacy, despite what must have been at the very least a strained coexistence. I imagine photographs of Guthrie and Carrel around that time having much the same quality.

As with Monsieur Gagny’s head, too much time (twenty minutes) had elapsed between the beheading and the moment circulation was restored for the dog head and brain to regain much function. Guthrie recorded a series of primitive movements and basic reflexes, similar to what Laborde and Hayem had observed: pupil contractions, nostril twitchings, “boiling movements” of the tongue. Only one notation in Guthrie’s lab notes gives the impression that the upside‑down dog head might have had an awareness of what had taken place: “5:31: Secretion of tears….” Both dogs were euthanized when complications set in, about seven hours after the operation.

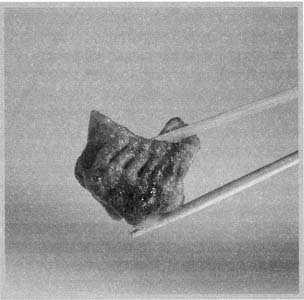

The first dog heads to enjoy, if that word can be used, full cerebral function were those of transplantation whiz Vladimir Demikhov, in the Soviet Union in the 1950s. Demikhov minimized the time that the severed donor head was without oxygen by using “blood‑vessel sewing machines.” He transplanted twenty puppy heads–actually, head‑shoulders‑lungs‑and‑forelimbs units with an esophagus that emptied, untidily, onto the outside of the dog–onto fully grown dogs, to see what they’d do and how long they’d last (usually from two to six days, but in one case as long as twenty‑nine days).

In his book Experimental Transplantation of Vital Organs , Demikhov includes photographs of, and lab notes from, Experiment No. 2, on February 24,1954: the transplantation of a one‑month‑old puppy’s head and forelimbs to the neck of what appears to be a Siberian husky. The notes portray a lively, puppylike, if not altogether joyous existence on the part of the head:

09:00. The donor’s head eagerly drank water or milk, and tugged as if trying to separate itself from the recipient’s body.

22:30. When the recipient was put to bed, the transplanted head bit the finger of a member of the staff until it bled.

February 26,18:00. The donor’s head bit the recipient behind the ear, so that the latter yelped and shook its head.

Demikhov’s transplant subjects were typically done in by immune reactions. Immunosuppressive drugs weren’t yet available, and the immune system of the intact dog would, understandably enough, treat the dog parts grafted to its neck as a hostile invader and proceed accordingly. And so Demikhov hit a wall. Having transplanted virtually every piece and combination of pieces of a dog into or onto another dog,[34]he closed up his lab and disappeared into obscurity.

If Demikhov had known more about immunology, his career might have gone quite differently. He might have realized that the brain enjoys what is known as “immunological privilege,” and can be kept alive on another body’s blood supply for weeks without rejection. Because it is protected by the blood brain barrier, it isn’t rejected the way other organs and tissues are. While the mucosal tissues of Guthrie’s and Demikhov’s transplanted dog heads began swelling and hemorrhaging within a day or two of the operation, the brains at autopsy appeared normal.

Here is where it begins to get strange.

In the mid‑1960s, a neurosurgeon named Robert White began experimenting with “isolated brain preparations”: a living brain taken out of one animal, hooked up to another animal’s circulatory system, and kept alive. Unlike Demikhov’s and Guthrie’s whole head transplants, these brains, lacking faces and sensory organs, would live a life confined to memory and thought. Given that many of these dogs’ and monkeys’ brains were implanted inside the necks and abdomens of other animals, this could only have been a blessing. While the inside of someone else’s abdomen is of moderate interest in a sort of curiosity‑seeking, Surgery Channel sort of way, it’s not the sort of place you want to settle down in to live out the remainder of your years.

White figured out that by cooling the brain during the procedure to slow the processes by which cellular damage occurs– a technique used today in organ recovery and transplant operations–it was possible to retain most of the organ’s normal functions. Which means that the personality–the psyche, the spirit, the soul–of those monkeys continued to exist, for days on end, without its body or any of its senses, inside another animal.

What must that have been like? What could possibly be the purpose, the justification? Had White been thinking of one day isolating a human brain like this? What kind of person comes up with a plan like this and carries it out?

To find out, I decided to go visit White in Cleveland, where he is spending his retirement. We planned to meet at the Metro Health Care Center, downstairs from the lab where he carried out his historic operations, which has been preserved as a kind of shrine‑cum‑media‑photo‑op. I was an hour early, and spent the time driving up and down Metro Health Care Drive, looking for a place to sit and have some coffee and review White’s papers. There was nothing. I ended up back at the hospital, on a patch of grass outside the parking garage. I had heard Cleveland had undergone some sort of renaissance, but apparently it underwent it in some other part of town. Let’s just say it wasn’t the sort of place I’d want to live out the remainder of my years, though it beats a monkey abdomen, and you can’t say that about some neighborhoods.

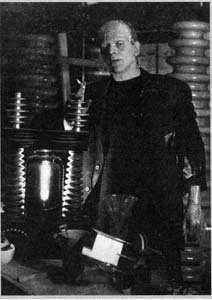

White escorts me through the hospital corridors and stairways, past the neurosurgery department, up the stairs, to his old lab. He is seventy‑six now, thinner than he was at the time of the operations, but elsewise little changed by age. His answers have the rote, patient air you expect from a man who has been asked the same questions a hundred times.

“Here we are,” says White, NEUROLOGICAL RESEARCH LABORATORY, says a plaque beside the door, giving away nothing. To step inside is to step back into 1968, before labs went white and stainless.

The counters are of a dull black stone, stained with white rings, and the cabinets and drawers are wood. It has been a while since anyone dusted, and ivy has grown over the one window. The fluorescent lights have those old covers that look like ice tray dividers.

“This is where we shouted ‘Eureka!’ and danced around,” recalls White.

There isn’t much room for dancing. It’s a small, cluttered, low‑ceilinged room, with a couple of stools for the scientists, and a downsized veterinary operating table for the rhesus monkeys.

And while White and his colleagues danced, what was going on inside the brain of that monkey? I ask him what he imagined it must have been like to find yourself, suddenly, reduced to your thoughts. I am, of course, not the first journalist to have asked this question. The legendary Oriana Fallaci[35]asked it of White’s neurophysiologist Leo Massopust, in a Look magazine interview in November 1967. “I suspect that without his senses he can think more quickly,” Dr. Massopust answered brightly. “What kind of thinking, I don’t know. I guess he’s primarily a memory, a repository for information stored when he had his flesh; he cannot develop further because he no longer has the nourishment of experience. Yet this, too, is a new experience.”

White declines to sugar‑coat. He mentions the isolation chamber studies of the 1970s, wherein subjects had no sensory input, nothing to hear, see, smell, feel, or taste. These people got as close as you can come, without White’s aid, to being brains in a box. “People [in these conditions] have gone literally crazy,” says White, “and it doesn’t take all that long.”

Although insanity, too, is a new experience for most people, no one was likely to volunteer to become one of White’s isolated brains. And of course, White couldn’t force anyone to do it–though I imagine Oriana Fallaci came to mind. “Besides,” says White, “I would question the scientific applicability. What would justify it?”

So what justified putting a rhesus monkey through it? It turns out the isolated brain experiments were simply a step on the way toward keeping entire heads alive on new bodies. By the time White appeared on the scene, early immunosuppressive drugs were available and many of the problems of tissue rejection were being resolved. If White and his team worked out the kinks with the brains and found they could be kept functioning, then they would move on to whole heads. First monkey heads, and then, they hoped, human ones.

Our conversation has moved from White’s lab to a booth in a nearby Middle Eastern restaurant. My recommendation to you is that you never eat baba ganoush or, for that matter, any soft, glistening gray food item while carrying on a conversation involving monkey brains.

White thinks of the operation not as a head transplant, but as a whole‑body transplant. Think of it this way: Instead of getting one or two donated organs, a dying recipient gets the entire body of a brain‑dead beating‑heart cadaver. Unlike Guthrie and Demikhov with their multiheaded monsters, White would remove the body donor’s head and put the new one in its place. The logical recipient of this new body, as White envisions it, would be a quadriplegic. For one thing, White said, the life span of quadriplegics is typically reduced, their organs giving out more quickly than is normal. By putting them–their heads– onto new bodies, you would buy them a decade or two of life, without, in their case, much altering their quality of life. High‑level quadriplegics are paralyzed from the neck down and require artificial respiration, but everything from the neck up works fine. Ditto the transplanted head.

Because no neurosurgeon can yet reconnect severed spinal nerves, the person would still be a quadriplegic–but no longer one with a death sentence. “The head could hear, taste, see,” says White. “It could read, and hear music. And the neck can be instrumented just like Mr. Reeve’s is, to speak.”

In 1971, White achieved the unthinkable. He cut the head off one monkey and connected it to the base of the neck of a second, decapitated monkey.

The operation lasted eight hours and required numerous assistants, each having been given detailed instructions, including where to stand and what to say. White went up to the operating room for weeks beforehand and marked off everyone’s position on the floor with chalk circles and arrows, like a football coach. The first step was to give the monkeys tracheotomies and hook them up to respirators, for their windpipes were about to severed. Next White pared the two monkey’s necks down to just the spine and the main blood vessels–the two carotid arteries carrying blood to the brain and the two jugular veins bringing it back to the heart.

Then he whittled down the bone on the top of the body donor’s neck and capped it with a metal plate, and did the same thing on the bottom of the head. (After the vessels were reconnected, the two plates were screwed together.) Then, using long, flexible tubing, he brought the circulation of the donor body over to supply its new head and sutured the vessels.

Finally, the head was cut off from the blood supply of its old body.

This is, of course, grossly simplified. I make it sound as though the whole thing could be done with a jackknife and a sewing kit. For more details, I would direct you to the July 1971 issue of Surgery , which contains White’s paper on the procedure, complete‑ with pen‑and‑ink illustrations. My favorite illustration shows a monkey body with a faint, ghostly head above its shoulders, indicating where its head had until recently been located, and a jaunty arrow arcing across the drawing toward the space above a second monkey body, where the first monkey’s head is now situated. The drawing lends a tidy, businesslike neutrality to what must have been a chaotic and exceptionally gruesome operation, much the way airplane emergency exit cards give an orderly, workaday air to the interiors of crashing planes. White filmed the operation but wouldn’t, despite protracted begging and wheedling, show me the film. He said it was too bloody.

That’s not what would have gotten to me. What would have gotten to me was the look on the monkey’s face when the anesthesia wore off and it realized what had just taken place. White described this moment in the aforementioned paper, “Cephalic Exchange Transplantation in the Monkey”: “Each cephalon [head] gave evidence of the external environment….The eyes tracked the movement of individuals and objects brought into their visual fields, and the cephalons remained basically pugnacious in their attitudes, as demonstrated by their biting if orally stimulated.” When White placed food in their mouths, they chewed it and attempted to swallow it–a bit of a dirty trick, given that the esophagus hadn’t been reconnected and was now a dead end. The monkeys lived anywhere from six hours to three days, most of them dying from rejection issues or from bleeding. (In order to prevent clotting in the anastomosed arteries, the animals were on anticoagulants, which created their own problems.)

I asked White whether any humans had ever stepped forward to volunteer their heads. He mentioned a wealthy, elderly quadriplegic in Cleveland who had made it clear that should the body transplant surgery be perfected when his time draws near, he’s game to give it a whirl.

“Perfected” being the key word. The trouble with human subjects is that no one wants to go first. No one wants to be a practice head.

If someone did agree to it, would White do it?

“Of course. I see no reason why it wouldn’t be successful with a man.”

White doesn’t think the United States will be the likely site of the first human head transplant, owing to the amount of bureaucracy and institutional resistance faced by inventors of radical new procedures.

“You’re dealing with an operation that is totally revolutionary. People can’t make up their minds whether it’s a total body transplant or a head transplant, a brain or even a soul transplant. There’s another issue too. People will say, ‘Look at all the people’s lives you could save with the organs in one body, and you want to give that body to just one person. And he’s paralyzed .’”

There are other countries, countries with less meddlesome regulating bodies, that would love to have White come over and make history swapping heads. “I could do it in Kiev tomorrow. And they’re even more interested in Germany and England. And the Dominican Republic. They want me to do it. Italy would like me to do it. But where’s the money?”

Even in the United States, cost stands in the way: As White points out, “Who’s going to fund the research when the operation is so expensive and would only benefit a small number of patients?”

Let’s say someone did fund the research, and that White’s procedures were streamlined and proved viable. Could there come a day when people whose bodies are succumbing to fatal diseases will simply get a new body and add decades to their lives–albeit, to quote White, as a head on a pillow? There could. Not only that, but with progress in repairing damaged spinal cords, surgeons may one day be able to reattach spinal nerves, meaning these heads could get up off their pillows and begin to move and control their new bodies. There’s no reason to think it couldn’t one day happen.

And few reasons to think it will. Insurance companies are unlikely to ever cover such an expensive operation, which would put this particular form of life extension out of reach of anyone but the very rich. Is it a sensible use of medical resources to keep terminally ill and extravagantly wealthy people alive? Shouldn’t we, as a culture, encourage a saner, more accepting attitude toward death? White doesn’t profess to have the last word on the matter. But he’d still like to do it.

Interestingly, White, a devout Catholic, is a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, some seventy‑eight well‑known scientific minds (and their bodies) who fly to Vatican City every two years to keep the Pope up to date on scientific matters of special interest to the church: stem cell research, cloning, euthanasia, even life on other planets. In one sense, this is an odd place for White, given that Catholicism preaches that the soul occupies the whole body, not just the brain. The subject came up during one of White’s meetings with the Holy Father. “I said to him, ‘Well, Your Holiness, I seriously have to consider that the human spirit or soul is physically located in the brain.’ The Pope looked very strained and did not answer.” White stops and looks down at his coffee mug, as though perhaps regretting his candor that day.

“The Pope always looks a little strained,” I point out helpfully. “I mean, with his health and all.” I wonder aloud whether the Pope might be a good candidate for total body transplant. “God knows the Vatican’s got the money….” White throws me a look. The look says it might not be a good idea to tell White about my collection of news photographs of the Pope having trouble with his vestments. It says I’m a petit bouchon fécal .

White would very much like to see the church change its definition of death from “the moment the soul leaves the body” to “the moment the soul leaves the brain,” especially given that Catholicism accepts both the concept of brain death and the practice of organ transplantation. But the Holy See, like White’s transplanted monkey heads, has remained pugnacious in its attitude.

No matter how far the science of whole body transplantation advances, White or anyone else who chooses to cut the head off a beating‑heart cadaver and screw a different one onto it faces a significant hurdle in the form of donor consent. A single organ removed from a body becomes impersonal, identity‑neutral. The humanitarian benefits of its donation outweigh the emotional discomfort surrounding its removal–for most of us, anyway. Body transplants are another story. Will people or their families ever give an entire, intact body away to improve the health of a stranger?

They might. It has happened before. Though these particular curative dead bodies never found their way to the operating room. They were more of an apothecary item: topically applied, distilled into a tincture, swallowed or eaten. Whole human bodies–as well as bits and pieces of them–were for centuries a mainstay in the pharmacopoeias of Europe and Asia. Some people actually volunteered for the job. If elderly men in twelfth‑century Arabia were willing to donate themselves to become “human mummy confection” (see recipe, next chapter), then it’s not hard to imagine that a man might volunteer to be someone else’s transplanted body. Okay, it’s maybe a little hard.

EAT ME

Medicinal Cannibalism and the Case of the Human Dumplings

In the grand bazaars of twelfth‑century Arabia, it was occasionally possible, if you knew where to look and you had a lot of cash and a tote bag you didn’t care about, to procure an item known as mellified man.

The verb “to mellify” comes from the Latin for honey, mel . Mellified man was dead human remains steeped in honey. Its other name was “human mummy confection,” though this is misleading, for, unlike other honey‑steeped Middle Eastern confections, this one did not get served for dessert. One administered it topically and, I am sorry to say, orally as medicine.

The preparation represented an extraordinary effort, both on the part of the confectioners and, more notably, on the part of the ingredients:

…In Arabia there are men 70 to 80 years old who are willing to give their bodies to save others. The subject does not eat food, he only bathes and partakes of honey. After a month he only excretes honey (the urine and feces are entirely honey) and death follows. His fellow men place him in a stone coffin full of honey in which he macerates. The date is put upon the coffin giving the year and month. After a hundred years the seals are removed. A confection is formed which is used for the treatment of broken and wounded limbs. A small amount taken internally will immediately cure the complaint.

The above recipe appears in the Chinese Materia Medica , a 1597 compendium of medicinal plants and animals compiled by the great naturalist Li Shih‑chen. Li is careful to point out that he does not know for certain whether the mellified man story is true. This is less comforting than it sounds, for it means that when Li Shih‑chen does not make a point of questioning the veracity of a Materia Medica entry, he feels certain that it is true. This tells us that the following were almost certainly used as medicine in sixteenth‑century China: human dandruff (“best taken from a fat man”), human knee dirt, human ear wax, human perspiration, old drumskins (“ashed and applied to the penis for difficult urination”), “the juice squeezed out of pig’s feces,” and “dirt from the proximal end of a donkey’s tail.”

The medicinal use of mummified–though not usually mellified–humans is well documented in chemistry books of sixteenth‑, seventeenth‑, and eighteenth‑century Europe, but nowhere outside Arabia were the corpses volunteers. The most sought‑after mummies were said to be those of caravan members overcome by sandstorms in the Libyan desert. “This sudden suffocation doth concentrate the spirits in all the parts by reason of the fear and sudden surprisal which seizes on the travellers,” wrote Nicolas Le Fèvre, author of A Compleat Body of Chymistry . (Sudden death also lessened the likelihood that the body was diseased.) Others claimed the mummy’s medicinal properties derived from Dead Sea bitumen, a pitchlike substance which the Egyptians were thought, at the time, to have used as an embalming agent.

Needless to say, the real deal out of Libya was scarce. Le Fèvre offered a recipe for home‑brewed mummy elixir using the remains of “a young, lusty man” (other writers further specified that the youth be a redhead). The requisite surprisal was to have been supplied by suffocation, hanging, or impalement. A recipe was provided for drying, smoking, and blending (one to three grains of mummy in a mixture of viper’s flesh and spirit of wine) the flesh, but Le Fèvre offered no hint of how or where to procure it, short of suffocating or impaling the young carrot‑top oneself.

There was for a time a trade in fake mummies being sold by Jews in Alexandria. They had apparently started out selling authentic mummies raided from crypts, prompting the author C. J. S. Thompson in The Mystery and Art of the Apothecary to observe that “the Jew eventually had his revenge on his ancient oppressors.” When stocks of real mummies wore thin, the traders began concocting fakes. Pierre Pomet, private druggist to King Louis XIV, wrote in the 1737 edition of A Compleat History of Druggs that his colleague Guy de la Fontaine had traveled to Alexandria to “have ocular demonstration of what he had heard so much of” and found, in one man’s shop, all manner of diseased and decayed bodies being doctored with pitch, wrapped in bandages, and dried in ovens. So common was this black market trade that pharmaceutical authorities like Pomet offered tips for prospective mummy shoppers:

“Choose what is of a fine shining black, not full of bones and dirt, of good smell and which being burnt does not stink of pitch.” A. C.Wootton, in his 1910 Chronicles of Pharmacy , writes that celebrated French surgeon and author Ambroise Paré claimed ersatz mummy was being made right in Paris, from desiccated corpses stolen from the gibbets under cover of night. Paré hastened to add that he never prescribed it. From what I can tell he was in the minority. Pomet wrote that he stocked it in his apothecary (though he averred that “its greatest use is for catching fish”).

C. J. S. Thompson, whose book was published in 1929, claimed that human mummy could still be found at that time in the drug‑bazaars of the Near East.

Mummy elixir was a rather striking example of the cure being worse than the complaint. Though it was prescribed for conditions ranging from palsy to vertigo, by far its most common use was as a treatment for contusions and preventing coagulation of blood: People were swallowing decayed human cadaver for the treatment of bruises . Seventeenth‑century druggist Johann Becher, quoted in Wootton, maintained that it was “very beneficial in flatulency” (which, if he meant as a causative agent, I do not doubt). Other examples of human‑sourced pharmaceuticals surely causing more distress than they relieved include strips of cadaver skin tied around the calves to prevent cramping, “old liquified placenta” to “quieten a patient whose hair stands up without cause” (I’m quoting Li Shih‑chen on this one and the next), “clear liquid feces” for worms (“the smell will induce insects to crawl out of any of the body orifices and relieve irritation”), fresh blood injected into the face for eczema (popular in France at the time Thompson was writing), gallstone for hiccoughs, tartar of human teeth for wasp bite, tincture of human navel for sore throat, and the spittle of a woman applied to the eyes for ophthalmia. (The ancient Romans, Jews, and Chinese were all saliva enthusiasts, though as far as I can tell you couldn’t use your own. Treatments would specify the type of spittle required: woman spittle, newborn man‑child spittle, even Imperial Saliva, Roman emperors apparently contributing to a community spittoon for the welfare of the people. Most physicians delivered the substance by eyedropper, or prescribed it as a sort of tincture, although in Li Shih‑chen’s day, for cases of “nightmare due to attack by devils,” the unfortunate sufferer was treated by “quietly spitting into the face.”)

Even in cases of serious illness, the patient was sometimes better off ignoring the doctor’s prescription. According to the Chinese Materia Medica , diabetics were to be treated with “a cupful of urine from a public latrine.” (Anticipating resistance, the text instructs that the heinous drink be “given secretly”) Another example comes from Nicholas Lemery, chemist and member of the Royal Academy of Sciences, who wrote that anthrax and plague could be treated with human excrement. Lemery did not take credit for the discovery, citing instead, in his A Course of Chymistry , a German named Homberg who in 1710 delivered before the Royal Academy a talk on the method of extracting “an admirable phosphorus from a man’s excrements, which he found out after much application and pains”; Lemery reported the method in his book (“Take four ounces of humane Excrement newly made, of ordinary consistency…”). Homberg’s fecal phosphorus was said to actually glow, an ocular demonstration of which I would give my eyeteeth (useful for the treatment for malaria, breast abscess, and eruptive smallpox) to see.

Homberg may have been the first to make it glow, but he wasn’t the first to prescribe it. The medical use of human feces had been around since Pliny’s day. The Chinese Materia Medica prescribes it not only in liquid, ash, and soup form–for everything from epidemic fevers to the treatment of children’s genital sores–but also in a “roasted” version. The thinking went that dung is essentially, in the case of the human variety,[36]bread and meat reduced to their simplest elements and thereby “rendered fit for the exercise of their virtues,” to quote A. C. Wootton.

Not all cadaveric medicines were sold by professional druggists. The Colosseum featured occasional backstage concessions of blood from freshly slain gladiators, which was thought to cure epilepsy,[37]but only if taken before it had cooled. In eighteenth‑century Germany and France, executioners padded their pockets by collecting the blood that flowed from the necks of guillotined criminals; by this time blood was being prescribed not only for epilepsy, but for gout and dropsy.[38]As with mummy elixir, it was believed that for human blood to be curative it must come from a man who had died in a state of youth and vitality, not someone who had wasted away from disease; executed criminals fit the bill nicely. It was when the prescription called for bathing in the blood of infants, or the blood of virgins, that things began to turn ugly. The disease in question was most often leprosy, and the dosage was measured out in bathtubs rather than eyedroppers. When leprosy fell upon the princes of Egypt, wrote Pliny, “woe to the people, for in the bathing chambers, tubs were prepared, with human blood for the cure of it.”

Often the executioners’ stock included human fat as well, which was used to treat rheumatism, joint pain, and the poetic‑sounding though probably quite painful falling‑away limbs. Body snatchers were also said to ply the fat trade, as were sixteenth‑century Dutch army surgeons in the war for independence from Spain, who used to rush onto the field with their scalpels and buckets in the aftermath of a pitched battle. To compete with the bargain basement prices of the executioners, whose product was packaged and sold more or less like suet, seventeenth‑century druggists would fancy up the goods by adding aromatic herbs and lyrical product names; seventeenth‑century editions of the Cordic Dispensatory included Woman Butter and Poor Sinner’s Fat. This had long been the practice with many of the druggists’ less savory offerings: Druggists in the Middle Ages sold menstrual blood as Maid’s Zenith and prettied it up with rosewater. C. J. S. Thompson’s book includes a recipe for Spirit of the Brain of Man, which includes not only brain (“with all its membranes, arteries, veins and nerves”), but peony, black cherries, lavender, and lily.

Thompson writes that the rationale behind many of the human remedies was simple association. Turning yellow from jaundice? Try a glass of urine. Losing your hair? Rub your scalp with distilled hair elixir. Not right in the head? Have a snort of Spirit of Skull. Marrow and oil distilled from human bones were prescribed for rheumatism, and human urinary sediment was said to counteract bladder stones.

In some cases, unseemly human cures were grounded in a sort of sideways medical truth. Bile didn’t cure deafness per se, but if your hearing problem was caused by a buildup of earwax, the acidy substance probably worked to dissolve it. Human toenail isn’t a true emetic, but one can imagine that an oral dose might encourage vomiting. Likewise, “clear liquid feces” isn’t a true antidote to poisonous mushrooms, but if getting mushrooms up and out of your patient’s stomach is the aim, there’s probably nothing quite as effective. The repellent nature of feces also explains its use as a topical application for prolapsed uterus. Since back before Hippocrates’ day, physicians had viewed the female reproductive system not as an organ but as an independent entity, a mysterious creature with a will of its own, prone to haphazard “wanderings.” If the uterus dropped down out of place following childbirth, a smear of something foul‑smelling–often dung–was prescribed to coax it back up where it belonged. The active ingredient in human saliva was no doubt the natural antibiotic it contains; this would explain its use in treating dog bite, eye infection, and “fetid perspiration,” even though no one at the time understood the mechanism.

Given that minor ailments such as bruises, coughs, dyspepsia, and flatulence disappear on their own in a matter of days, it’s easy to see how rumors of efficacy came about. Controlled trials were unheard of; everything was based on anecdotal evidence. We gave Mrs. Peterson some shit for her quinsy and now she’s doing fine! I talked to Robert Berkow, editor of the Merck Manual , for 104 years the best‑selling physicians’ reference book, about the genesis of bizarre and wholly unproven medicines. “When you consider that a sugar pill for pain relief will get a twenty‑five to forty percent response,” he said, “you can begin to understand how some of these treatments came to be recommended.” It wasn’t until about 1920, he added, that “the average patient with the average illness seeing the average physician came off better for the encounter.”

The popularity of some of these human elixirs probably had less to do with the purported effective ingredient than with the base. The recipe in Thompson’s book for a batch of King Charles’ Drops–King Charles II ran a brisk side business in human skull tinctures out of his private laboratory in Whitehall–contained not only Spirit of Skull but a half pound of opium and four fingers (the unit of measurement, not the actual digits) of spirit of wine. Mouse, goose, and horse excrements, used by Europeans to treat epilepsy, were dissolved in wine or beer. Likewise powdered human penis, as prescribed in the Chinese Materia Medica , was “taken with alcohol.” The stuff might not cure you, but it would ease the pain and put a shine on your mood.

Off‑putting as cadaveric medicine may be, it is–like cultural differences in cuisine–mainly a matter of what you’re accustomed to. Treating rheumatism with bone marrow or scrofula with sweat is scarcely more radical or ghoulish than treating, say, dwarfism with human growth hormone. We see nothing distasteful in injections of human blood, yet the thought of soaking in it makes us cringe. I’m not advocating a return to medicinal earwax, but a little calm is in order. As Bernard E. Read, editor of the 1976 edition of the Chinese Materia Medica , pointed out, “Today people are feverishly examining every type of animal tissue for active principles, hormones, vitamines and specific remedies for disease, and the discovery of adrenaline, insulin, theelin, menotoxin, and others, compels an open mind that one may reach beyond the unaesthetic setting of the subject to things worth while.”

Those of us who undertook the experiment pooled our money to purchase cadavers from the city morgue, choosing the bodies of persons who had died of violence–who had been freshly killed and were not diseased or senile. We lived on this cannibal diet for two months and everyone’s health improved.

So wrote the painter Diego Rivera in his memoir, My Art, My Life . He explains that he’d heard a story of a Parisian fur dealer who fed his cats cat meat to make their pelts firmer and glossier. And that in 1904, he and some fellow anatomy students– anatomy being a common requirement for art students– decided to try it for themselves. It’s possible Rivera made this up, but it makes a lively introduction to modern‑day human medicinals, so I thought I’d throw it in.

Outside of Rivera, the closest anyone has gotten to Spirit of Skull or Maid’s Zenith in the twentieth century is in the medicinal use of cadaver blood. In 1928, a Soviet surgeon by the name of V. N. Shamov attempted to see if blood from the dead could be used in place of blood from live donors for transfusions. In the Soviet tradition, Shamov experimented first on dogs. Provided the blood was removed from the corpse within six hours, he found, the transfused canines showed no adverse reactions. For six to eight hours, the blood inside a dead body remains sterile and the red blood cells retain their oxygen‑carrying capabilities.

Two years later, the Sklifosovsky Institute in Moscow got wind of Shamov’s work and began trying it out on humans. So enamored of the technique were they that a special operating room was built to which cadavers were delivered. “The cadavers are brought by first‑aid ambulances from the street, offices, and other places where sudden death overtakes human beings,” wrote B. A. Petrov in the October 1959 issue of Surgery . Robert White, the neurosurgeon from Chapter 9, told me that during the Soviet era, cadavers belonged officially to the state, and if the state wanted to do something with them, then do something it did. (Presumably the bodies, once drained, were returned to the family.) Corpses donate blood much the way people do, except that the needle goes in at the neck instead of the arm, and the body, lacking a working heart, has to be tilted so the blood pours out, rather than being pumped.

The cadaver, wrote Petrov, was to be placed in “the extreme Trendelenburg position.” His paper includes a line drawing of the jugular vein being entubed and a photograph of the special sterile ampules into which the blood flows, though in my opinion the space would have been better used to illustrate the intriguing and mysterious Trendelenburg position. I am intrigued only because I spent a month with a black‑and‑white photograph of the “Sims position for gynecological examination”[39]on my wall, courtesy of the 2001 Mütter Museum calendar. (“The patient is to lie on the left side,” wrote Dr. Sims. “The thighs are to be flexed, …the right being drawn up a little more than the left. The left arm is thrown behind across the back and the chest rotated forwards.” It is a languorous, highly provocative position, and one has to wonder whether it was the ease of access it afforded or the similarity to cheesecake poses of the day that led our Dr. Sims to promote its use.)

The Trendelenburg position, I found out (by reading “Beyond the Trendelenburg Position: Friedrich Trendelenburg’s Life and Surgical Contributions” in the journal Surgery , for I am easily distracted) simply refers to lying in a 45‑degree incline; Trendelenburg used it during genitourinary surgery to tilt the abdominal organs up and out of the way.

The paper’s authors describe Trendelenburg as a great innovator, a giant in the field of surgery, and they mourn the fact that such an accomplished man is remembered for one of his slightest contributions to medical science. I will compound the crime by mentioning another of his slight contributions to medical science, the use of “Havana cigars to improve the foul hospital air.” Ironically, the paper identified Trendelenburg as an outspoken critic of therapeutic bloodletting, though he registered no opinion on the cadaveric variety.

For twenty‑eight years, the Sklifosovsky Institute happily transfused cadaver blood, some twenty‑five tons of the stuff, meeting 70 percent of its clinics’ needs. Oddly or not so oddly, cadaver blood donation failed to catch on outside the Soviet Union. In the United States, one man and one man alone dared try it. It seems Dr. Death earned his nickname long before it was given to him. In 1961, Jack Kevorkian drained four cadavers according to the Soviet protocol and transfused their blood into four living patients. All responded more or less as they would have had the donor been alive. Kevorkian did not tell the families of the dead blood donors what he was doing, using the rationale that blood is drained from bodies anyway during embalming. He also remained mum on the recipient end, opting not to tell his four unwitting subjects that the blood flowing into their veins came from a corpse. His rationale in this case was that the technique, having been done for thirty years in the Soviet Union, was clearly safe and that any objections the patients might have had would have been no more than an “emotional reaction to a new and slightly distasteful idea.” It’s the sort of defense that might work well for those maladjusted cooks that you hear about who delight in jerking off into the pasta sauce.

Of all the human parts and pieces mentioned in the Chinese Materia Medica and in the writings of Thompson, Lemery, and Pomet, I could find only one other in use as medicine today. Placenta is occasionally consumed by European and American women to stave off postpartum depression. You don’t get placenta from the druggist as you did in Lemery’s or Li Shih‑chen’s time (to relieve delirium, weakness, loss of willpower, and pinkeye); you cook and eat your own. The tradition is sufficiently mainstream to appear on a half‑dozen pregnancy Web sites.

The Virtual Birth Center tells us how to prepare Placenta Cocktail (8 oz. V‑8, 2 ice cubes, ½ cup carrot, and ¼ cup raw placenta, puréed in a blender for 10 seconds), Placenta Lasagna, and Placenta Pizza. The latter two suggest that someone other than Mom will be partaking–that it’s being cooked up for dinner, say, or the PTA potluck–and one dearly hopes that the guests have been given a heads‑up. The U.K.‑based Mothers 35 Plus site lists “several sumptuous recipes,” including roast placenta and dehydrated placenta. Ever the trailblazers, British television aired a garlic‑fried placenta segment on the popular Channel 4 cooking show TV Dinners . Despite what one news report described as “sensitive” treatment of the subject, the segment, which ran in 1998, garnered nine viewer complaints and a slap on the wrist from the Broadcasting Standards Commission.

To see whether any of the human Chinese Materia Medica preparations are still used in modern China, I contacted the scholar and author Key Ray Chong, author of Cannibalism in China . Under the bland and benign‑sounding heading “Medical Treatment for Loved Ones,” Chong describes a rather gruesome historical phenomenon wherein children, most often daughters‑in‑law, were obliged to demonstrate filial piety to ailing parents, most often mothers‑in‑law, by hacking off a piece of themselves and preparing it as a restorative elixir. The practice began in earnest during the Sung Dynasty (960‑1126) and continued through the Ming Dynasty, and up to the early 1900s. Chong presents the evidence in the form of a list, each entry detailing the source of the information, the donor, the beneficiary, the body part removed, and the type of dish prepared from it. Soups and porridges, always popular among the sick, were the most common dishes, though in two instances broiled flesh–one right breast and one thigh/upper arm combo–was served. In what may well be the earliest documented case of stomach reduction, one enterprising son presented his father with “lard of left waist.” Though the list format is easy on the eyes, there are instances where one aches for more information: Did the young girl who gave her mother‑in‑law her left eyeball do so to prove the depth of her devotion, or to horrify and spite the woman? Examples for the Ming Dynasty were so numerous that Chong gave up on listing individual instances and presented them instead as tallies by category: In total, some 286 pieces of thigh, thirty‑seven pieces of arm, twenty‑four livers, thirteen unspecified cuts of flesh, four fingers, two ears, two broiled breasts, two ribs, one waist loin, one knee, and one stomach skin were fed to sickly elders.

Interestingly, Li Shih‑chen disapproved of the practice. “Li Shih‑chen acknowledged these practices among the ignorant masses,” wrote Read, “but he did not consider that any parent, however ill, should expect such sacrifices from their children.” Modern Chinese no doubt agree with him, though reports of the practice occasionally crop up. Chong cites a Taiwan News story from May 1987 in which a daughter cut off a piece of her thigh to cook up a cure for her ailing mother.

Although Chong writes in his book that “even today, in the People’s Republic of China, the use of human fingers, toes, nails, dried urine, feces and breast milk are strongly recommended by the government to cure certain diseases” (he cites the 1977 Chung Yao Ta Tz’u Tien , the Great Dictionary of Chinese Pharmacology) , he could not put me in touch with anyone who actually partakes, and I more or less abandoned my search.

Then, several weeks later, an e‑mail arrived from him. It contained a story from the Japan Times that week, entitled “Three Million Chinese Drink Urine.” Around that same time, I happened upon a story on the Internet, originally published in the London Daily Telegraph , which based its story on one from the day before in the now‑defunct Hong Kong Eastern Express . The article stated that private and state‑run clinics and hospitals in Shenzhen, outside Hong Kong, sold or gave away aborted fetuses as a treatment for skin problems and asthma and as a general health tonic. “There are ten foetuses here, all aborted this morning,” the Express reporter claims she was told while visiting the Shenzhen Health Centre for Women and Children undercover and asking for fetuses.

“Normally we doctors take them home to eat. Since you don’t look well, you can take them.” The article bordered on the farcical. It had hospital cleaning women “fighting each other to take the treasured human remains home,” sleazy unnamed chaps in Hong Kong back alleys charging $300 per fetus, and a sheepish businessman “introduced to foetuses by friends” furtively making his way to Shenzhen with his Thermos flask every couple of weeks to bring back “20 or 30 at a time” for his asthma.

In both this instance and that of the three million urine‑quaffing Chinese, I didn’t know whether the reports were true, partially true, or instances of bald‑faced Chinese‑bashing. Aiming to find out, I contacted Sandy Wan, a Chinese interpreter and researcher who had done work for me before in China. As it turned out, Sandy used to live in Shenzhen, had heard of the clinics mentioned in the article, and still had friends there–friends who were willing to pose, bless their hearts, as fetus‑seeking patients. Her friends, a Miss Wu and a Mr. Gai, started out at the private clinics, saying they’d heard it was possible to buy fetuses for medicinal purposes. Both got the same answer: It used to be possible, but the government of Shenzhen had some time ago declared it illegal to sell both fetuses and placentas. The two were told that the materials were collected by a “health care production company with a unified management.” It soon became clear what that meant and what was being done with the “materials.” At the state‑run Shenzhen People’s Hospital, the region’s largest, Miss Wu went to the Chinese medicine department to ask a doctor for treatment for the blemishes on her face. The doctor recommended a medication called Tai Bao Capsules, which were sold in the hospital dispensary for about $2.50 a bottle. When Miss Wu asked what the medication was, the doctor replied that it was made from abortus, as it is called there, and placenta, and that it was very good for the skin. Meanwhile, over in the internal medicine department, Mr. Gai had claimed to have asthma and told the doctor that his friends had recommended abortus. The doctor said he hadn’t heard of selling fetuses

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-05-08; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 1261;