WHY WE EAT WHAT WE EAT AND DESPISE THE REST

T HE NORTHERN FOOD Tradition and Health Resource Kit contains a deck of forty‑eight labeled photographs of traditional Inuit foods. Most are meat, but none are steaks. Seal Heart, one is labeled. Caribou Brain, says another. The images, life‑size where possible, are printed on stiff paper and die‑cut, like paper dolls that you badly want to throw some clothes on. The kit I looked through belonged to Gabriel Nirlungayuk, a community health representative from Pelly Bay, a hamlet in Canada’s Nunavut territory. Like me, he was visiting Igloolik–a town on a small island near Baffin Island–to attend an Arctic athletic competition.[18]With him was Pelly Bay’s mayor at the time, Makabe Nartok. The three of us met by chance in the kitchen of Igloolik’s sole lodgings, the Tujormivik Hotel.

Nirlungayuk’s job entailed visiting classrooms to encourage young Inuit “chip‑aholics and pop‑aholics” to eat like their elders. As the number of Inuit who hunt has dwindled, so has the consumption of organs (and other anatomy not available for purchase at the Igloolik Co‑op: tendons, blubber, blood, head).

I picked up the card labeled Caribou Kidney, Raw. “Who actually eats this?”

“I do,” said Nirlungayuk. He is taller than most Inuit, with a prominent, thrusting chin that he used to indicate Nartok. “He does.”

Anyone who hunts, the pair told me, eats organs. Though the Inuit (in Canada, the term is preferred over Eskimo ) gave up their nomadic existence in the 1950s, most adult men still supplemented the family diet with hunted game, partly to save money. In 1993, when I visited, a small can of Spork, the local Spam, cost $2.69. Produce arrives by plane. A watermelon might set you back $25. Cucumbers were so expensive that the local sex educator did his condom demonstrations on a broomstick.

I asked Nartok to go through the cutouts and show me what he ate. He reached across the table to take them from me. His arms were pale to the wrist, then abruptly brown. The Arctic suntan could be mistaken, at a glance, for gloves. He peered at the cutouts through wire‑rim glasses. “Caribou liver, yes. Brain. Yes, I eat brain. I eat caribou eyes, raw and cooked.” Nirlungayuk looked on, nodding.

“I like this part very much.” Nartok was holding a cutout labeled Caribou Bridal Veil. This is a prettier way of saying “stomach membrane.” It was dawning on me that eating the whole beast was a matter not just of economics but of preference. At a community feast earlier in the week, I was offered “the best part” of an Arctic char. It was an eye, with fat and connective tissue dangling off the back like wiring on a headlamp. A cluster of old women stood by a chain‑link fence digging marrow from caribou bones with the tilt‑headed focus nowadays reserved for texting.

For Arctic nomads, eating organs has, historically, been a matter of survival. Even in summer, vegetation is sparse. Little beyond moss and lichen grows abundantly on the tundra. Organs are so vitamin‑rich, and edible plants so scarce, that the former are classified, for purposes of Arctic health education, both as “meat” and as “fruits and vegetables.” One serving from the Fruits and Vegetables Group in Nirlungayuk’s materials is “1/2 cup berries or greens, or 60 to 90 grams of organ meats.”

Nartok shows me an example of Arctic “greens”: cutout number 13, Caribou Stomach Contents. Moss and lichen are tough to digest, unless, like caribou, you have a multichambered stomach in which to ferment them. So the Inuit let the caribou have a go at it first. I thought of Pat Moeller and what he’d said about wild dogs and other predators eating the stomachs and stomach contents of their prey first. “And wouldn’t we all,” he’d said, “be better off.”

If we could strip away the influences of modern Western culture and media and the high‑fructose, high‑salt temptations of the junk‑food sellers, would we all be eating like Inuit elders, instinctively gravitating to the most healthful, nutrient‑diverse foods? Perhaps. It’s hard to say. There is a famous study from the 1930s involving a group of orphanage babies who, at mealtimes, were presented with a smorgasbord of thirty‑four whole, healthy foods. Nothing was processed or prepared beyond mincing or mashing. Among the more standard offerings–fresh fruits and vegetables, eggs, milk, chicken, beef–the researcher, Clara Davis, included liver, kidney, brains, sweetbreads, and bone marrow. The babies shunned liver and kidney (as well as all ten vegetables, haddock, and pineapple), but brains and sweetbreads did not turn up among the low‑preference foods she listed. And the most popular item of all? Bone marrow.

A T HALF PAST ten, the sky was princess pink. There was still enough light to make out the walrus appliqués on the jacket of a young girl riding her bicycle on the gravel road through town. We were joined in the kitchen by a man named Marcel, just back from a hunting camp where a pod of narwhal had been spotted earlier in the day. The narwhal is a medium‑sized whale with a single tusk protruding from its head like a birthday candle.

Marcel dropped a white plastic bag onto the table. It bounced slightly on landing. “Muktuk,” Nirlungayuk said approvingly. It was a piece of narwhal skin, uncooked. Nartok waved it off. “I ate muktuk earlier. Whole lot.” In the air he outlined a square the size of a hardback book.

Nirlungayuk speared a chunk on the tip of a pocketknife blade and held it out for me. My instinct was to refuse it. I’m a product of my upbringing. I grew up in New Hampshire in the 1960s, when meat meant muscle. Breast and thigh, burgers and chops. Organs were something you donated. Kidney was a shape for coffee tables. It did not occur to my people to fix innards for supper, especially raw ones. Raw outards seemed even more unthinkable.

I pulled the rubbery chunk from Nirlungayuk’s knife. It was cold from the air outside and disconcertingly narwhal‑colored. The taste of muktuk is hard to pin down. Mushrooms? Walnut? There was plenty of time to think about it, as it takes approximately as long to chew narwhal as it does to hunt them. I know you won’t believe me, because I didn’t believe Nartok, but muktuk is exquisite (and, again, healthy: as much vitamin A as in a carrot, plus a respectable amount of vitamin C).

I like chicken skin and pork rinds. Why the hesitation over muktuk? Because to a far greater extent than most of us realize, culture writes the menu. And culture doesn’t take kindly to substitutions.

W HAT GABRIEL NIRLUNGAYUK was trying to do with organs for health, the United States government tried to do for war. During World War II, the U.S. military was shipping so much meat overseas to feed troops and allies that a domestic shortage loomed. According to a 1943 Breeder’s Gazette article, the American soldier consumed close to a pound of meat a day. Beginning that year, meat on the homefront was rationed–but only the mainstream cuts. You could have all the organ meats you wanted. The army didn’t use them because they spoiled more quickly and because, as Life put it, “the men don’t like them.”

Civilians didn’t like them any better. Hoping to change this, the National Research Council (NRC) hired a team of anthropologists, led by the venerable Margaret Mead, to study American food habits. How do people decide what’s good to eat, and how do you go about changing their minds? Studies were undertaken, recommendations drafted, reports published–including Mead’s 1943 opus “The Problem of Changing Food Habits: Report of the Committee on Food Habits,” and if ever a case were to be made for word‑rationing, there it was.

The first order of business was to come up with a euphemism. People were unlikely to warm to a dinner of “offal” or “glandular meats,” as organs were called in the industry.[19]“Tidbits” turned up here and there–as in Life’ s poetic “Plentiful are these meats called ‘tidbits’”–but “variety meats” was the standout winner. It had a satisfactorily vague and cheery air, calling to mind both protein and primetime programming with dance numbers and spangly getups. In the same vein–ew! Sorry. Similarly, meal planners and chefs were encouraged “to give special attention to the naming” of new organ‑meat entrées. A little French was thought to help things go down easier. A 1944 Hotel Management article included recipes for “Brains à la King” and “Beef Tongue Piquant.”

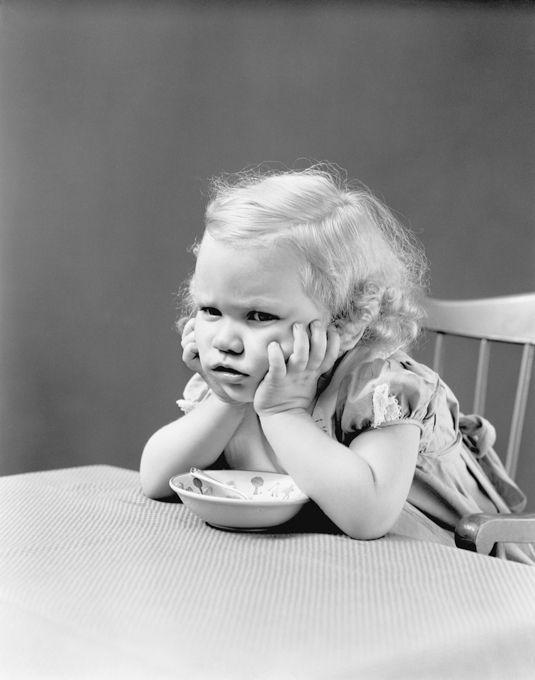

Another strategy was to target kids. “The human infant enters the world without information about what is edible and what is not,” wrote psychologist Paul Rozin, who studied disgust for many years at the University of Pennsylvania. Until kids are around two, you can get them to try pretty much anything, and Rozin did. In one memorable study, he tallied the percentage of children aged sixteen to twenty‑nine months who ate or tasted the following items presented to them on a plate: fish eggs (60 percent), dish soap (79 percent), cookies topped with ketchup (94 percent), a dead (sterilized) grasshopper (30 percent), and artfully coiled peanut butter scented with Limburger cheese and presented as “dog‑doo” (55 percent). The lowest‑ranked item, at 15 percent acceptance, was a human hair.[20]

By the time children are ten years old, generally speaking, they’ve learned to eat like the people around them. Once food prejudices are set, it is no simple task to dissolve them. In a separate study, Rozin presented sixty‑eight American college students with a grasshopper snack, this time a commercially prepared honey‑covered variety sold in Japan. Only 12 percent were willing to try one.

So the NRC tried to get elementary schools involved. Home economists were urged to approach teachers and lunch planners. “Let’s do more than say ‘How do you do’ to variety meats; let’s make friends with them!” chirps Jessie Alice Cline in the February 1943 Practical Home Economics. The War Food Administration pulled together a Food Conservation Education brochure with suggested variety‑meat essay themes (“My Adventures in Eating New Foods”). Perhaps sensing the futility of trying to get ten‑year‑olds to embrace brains and hearts, the administration focused mainly on not wasting food. One suggested student activity took the form of “a public display of wasted edible food actually found in the garbage dump,” which does more than say “How do you do” to a long night of parental phone calls.

The other problem with classroom‑based efforts to change eating habits was that children don’t decide what’s for dinner. Mead and her team soon realized they had to get to the person they called the “gatekeeper”–Mom. Nirlungayuk reached a similar conclusion. I tracked him down, seventeen years later, and asked him what the outcome of his country‑foods campaign had been. “It didn’t really work,” he said, from his office in the Nunavut department of wildlife and environment. “Kids eat what parents make for them. That’s one thing I didn’t do is go to the parents.”

Even that can flop. Mead’s colleague Kurt Lewin, as part of the NRC research, gave a series of lectures to homemakers on the nutritional benefits of organ meats, ending with a plea for patriotic cooperation.[21]Based on follow‑up interviews, just 10 percent of the women who’d attended had gone home and prepared a new organ meat for the family. Discussion groups were more effective than lectures, but guilt worked best of all. “They said to the women, ‘A lot of people are making a lot of sacrifices in this war,’” says Brian Wansink, author of “Changing Eating Habits on the Home Front.” “‘You can do your part by trying organ meats.’ All of a sudden, it was like, ‘Well, I don’t want to be the only person not doing my part.’”

Also effective: pledges. Though it now seems difficult to picture it, Wansink says government anthropologists had PTA members stand up and recite, “I will prepare organ meats at least ____ times in the coming two weeks.” “The act of making a public commitment,” said Wansink, “was powerful, powerful, powerful.” A little context here: The 1940s was the heyday of pledges and oaths.[22]In Boy Scout halls, homerooms, and Elks lodges, people were accustomed to signing on the dotted line or standing and reciting, one hand raised. Even the Clean Plate Club–dreamed up by a navy commander in 1942–had an oath: “I, ____, being a member in good standing…, hereby agree that I will finish all the food on my plate… and continue to do so until Uncle Sam has licked the Japs and Hitler”–like, presumably, a plate.

To open people’s minds to a new food, you sometimes just have to get them to open their mouths. Research has shown that if people try something enough times, they’ll probably grow to like it. In a wartime survey conducted by a team of food‑habits researchers, only 14 percent of the students at a women’s college said they liked evaporated milk. After serving it to the students sixteen times over the course of a month, the researchers asked again. Now 51 percent liked it. As Kurt Lewin put it, “People like what they eat, rather than eat what they like.”

The phenomenon starts early. Breast milk and amniotic fluid carry the flavors of the mother’s foods, and studies consistently show that babies grow up to be more accepting of flavors they’ve sampled while in the womb and while breastfeeding. (Babies swallow several ounces of amniotic fluid a day.) Julie Mennella and Gary Beauchamp of the Monell Chemical Senses Center have done a great deal of work in this area, even recruiting sensory panelists to sniff[23]amniotic fluid (withdrawn during amniocentesis) and breast milk from women who had and those who hadn’t swallowed a garlic oil capsule. Panelists agreed: the garlic‑eaters’ samples smelled like garlic. (The babies didn’t appear to mind. On the contrary, the Monell team wrote, “Infants… sucked more when the milk smelled like garlic.”)

As a food marketing consultant, Brian Wansink was involved in efforts to increase global consumption of soy products. Whether one succeeds at such an undertaking, he found, depends a great deal on the culture whose diet you seek to change. Family‑oriented countries where eating and cooking are firmly bound by tradition–Wansink gives the examples of China, Colombia, Japan, and India–are harder to infiltrate. Cultures like the United States and Russia, where there’s less cultural pressure to follow tradition and more emphasis on the individual, are a better bet.

Price matters too, though not always how you think it would. Saving money can be part of the problem. The well‑known, long‑standing cheapness of offal, Mead wrote, condemned it to the wordy category “edible for human beings but not by own kind of human being.” Eating organs, in 1943, could degrade one’s social standing. Americans preferred bland preparations of muscle meat partly because for as long as they could recall, that’s what the upper class ate.

So powerful are race‑ and status‑based disgusts that explorers have starved to death rather than eat like the locals. British polar exploration suffered heavily for its mealtime snobbery. “The British believed that Eskimo food… was beneath a British sailor and certainly unthinkable for a British officer,” wrote Robert Feeney in Polar Journeys: The Role of Food and Nutrition in Early Exploration. Members of the 1860 Burke and Wills expedition to cross Australia fell prey to scurvy or starved in part because they refused to eat what the indigenous Australians ate. Bugong‑moth abdomen and witchetty grub may sound revolting, but they have as much scurvy‑battling vitamin C as the same size serving of cooked spinach, with the additional benefits of potassium, calcium, and zinc.

Of all the so‑called variety meats, none presents a steeper challenge to the food persuader than the reproductive organs. Good luck to Deanna Pucciarelli, the woman who seeks to introduce mainstream America to the culinary joys of pig balls. “I am indeed working on a project on pork testicles,” said Pucciarelli, director of the Hospitality and Food Management Program at–fill my heart with joy!–Ball State University. Because she was bound by a confidentiality agreement, Pucciarelli could not tell me who would be serving them or why or what form they would take. Setting aside alleged fertility enhancers and novelty dare items (for example, “Rocky Mountain oysters”), the reproductive equipment seem to have managed to stay off dinner plates worldwide. Neither I nor Janet Riley, spokesperson for the American Meat Institute, could come up with a contemporary culture that regularly partakes of ovaries, uterus, penis, or vagina simply as something good to eat.

Historically, there was ancient Rome. Bruce Kraig, president of the Culinary Historians of Chicago, passed along a recipe from Apicius , for sow uterus sausage. For a cookbook, Apicius has a markedly gladiatorial style. “Remove the entrails by the throat before the carcass hardens immediately after killing,” begins one recipe. Where a modern recipe might direct one to “salt to taste,” the uterus recipe says to “add cooked brains, as much as is needed.” Sleeter Bull,[24]the author of the 1951 book Meat for the Table , claims the ancient Greeks had a taste for udders. Very specifically, “the udders of a sow just after she had farrowed but before she had suckled her pigs.” That is either the cruelest culinary practice in history or so much Sleeter bull.

I would wager that if you look hard enough, you will find a welcoming mouth for any safe source of nourishment, no matter how unpleasant it may strike you. “If we consider the wide range of foods eaten by all human groups on earth, one must… question whether any edible material that provides nourishment with no ill effects can be considered inherently disgusting,” writes the food scientist Anthony Blake. “If presented at a sufficiently early age with positive reinforcement from the childcarer, it would become an accepted part of the diet.” As an example, Blake mentions a Sudanese condiment made from fermented cow urine and used as a flavor enhancer “very much in the way soy sauce is used in other parts of the world.”

The comparison was especially apt in the summer of 2005, when a small‑scale Chinese operation was caught using human hair instead of soy to make cheap ersatz soy sauce. Our hair is as much as 14 percent L‑cysteine, an amino acid commonly used to make meat flavorings and to elasticize dough in commercial baking. How commonly? Enough to merit debate among scholars of Jewish dietary law, or kashrut. “Human hair, while not particularly appetizing, is Kosher,” states Rabbi Zushe Blech, the author of Kosher Food Production , on Kashrut.com “There is no ‘guck’ factor,” Blech maintained, in an e‑mail. Dissolving hair in hydrochloric acid, which creates the L‑cysteine, renders it unrecognizable and sterile. The rabbis’ primary concern had not to do with hygiene but with idol worship. “It seems that women would grow a full head of hair and then shave it off and offer it to the idol,” wrote Blech. Shrine attendants in India have been known to surreptitiously collect the hair and sell it to wigmakers, and some in kashrut circles worried they might also be selling it to L‑cysteine[25]producers. This proved not to be the case. “The hair used in the process comes exclusively from local barber shops,” Blech assures us. Phew.

• • •

T HE MOST EFFECTIVE agent of dietary change is the adulated eater–the king who embraces whelks, the revolutionary hero with a passion for skewered hearts. “Normally disgusting substances or objects that are associated with admired… persons cease to be disgusting and may become pleasant,” writes Paul Rozin. For organ meats today, that person has been taking the form of celebrity chefs at high‑profile eateries, such as Los Angeles’s Animal and London’s St. John, and on Food Network programs. On the Iron Chef episode “Battle Offal,” judges swooned over raw heart tartar, lamb’s liver truffles, tripe, sweetbreads, and gizzard. If things go as they usually go, hearts and sweetbreads might start to show up on home dinner tables in five or ten years.

Time and again, AFB’s Pat Moeller has watched the progression with ethnic cuisines: from upscale restaurant to local eatery to dinner table to supermarket freezer section. “It starts as an appetizer typically. That’s low risk. Then it migrates to an entrée dish. Then it becomes a food that you can buy and take home and fix for your family.”

With organ meats, where the prep may include, say, “removal of membrane,” the last phase will be slow‑going. Unlike filets and stewing meats, organs look like what they are: body parts. That’s another reason we resist them. “Organs,” says Rozin, “remind us of what we have in common with animals.” In the same way a corpse spawns thoughts of mortality, tongues and tripe send an unwelcome message: you too are an organism, a chewing, digesting sack of guts.

To eat liver, knowing that you, too, have a liver, brushes up against the cannibalism taboo. The closer we are to a species, emotionally or phylogenetically, the more potent our horror at the prospect of tucking in, the more butchery feels like murder. Pets and primates, wrote Mead, come under the category “unthinkable to eat.” The same cultures that eat monkey meat have traditionally drawn the line at apes.

The Inuit, at the time I visited Igloolik, had no tradition of keeping animals as companions. A sled dog was more or less a piece of equipment. When I told Makabe Nartok that I had a cat, he asked, “What do you use it for?” In America, pets are family, never fare. That feeling held fast even during the years of World War II rationing, when horse or rabbit–delicacies right over the pond in France–might, you’d think, have seemed preferable to organs. In the 1943 opinion piece “Jackrabbit Should Be Used to Ease Meat Shortage,” Kansas City scientist B. Ashton Keith bemoans the “wasted meat resource” of jackrabbit carcasses that were being left for coyotes and crows after being killed by ranchers in “great drives that slaughter thousands.” (Most of these seemingly collected by Keith’s mother: “Some of the pleasantest recollections of my boyhood are of fried jackrabbit, baked jackrabbit, jackrabbit stew, and jackrabbit pie.”)

S ELF‑MADE “NUTRITIONAL ECONOMIST” Horace Fletcher espoused a singular approach to getting Americans through a wartime meat shortage without resorting to rationing, or jackrabbits. What Fletcher proposed was a simple if burdensome adjustment to the human machinery.

4. The Longest Meal

Äàòà äîáàâëåíèÿ: 2015-05-08; ïðîñìîòðîâ: 2369;