FRUSTRATIONS WITH THE SEAD EFFORT

In contrast to the far more satisfying SEAD experience in Desert Storm, the initial effort to suppress Serb air defenses in Allied Force did not go nearly as well as expected. The avowed going‑in objective of the SEAD operation was to neutralize as many of Serbia’s SAMs and AAA sites as possible, particularly its estimated 16 SA‑3 LOW BLOW and 25 SA‑6 STRAIGHT FLUSH fire control radars. Another early goal was to take out or suppress long‑range surveillance radars that could provide timely threat warning to MANPADS operators carrying shoulder‑fired infrared SAMs like the SA‑7.

The Serbs, however, kept their SAMs defensively dispersed and operating in an emission control (EMCON) mode, prompting concern that they were attempting to draw NATO aircraft down to lower altitudes where they could be more easily engaged. Before the initial strikes, there were reports of a large‑scale dispersal of SA‑3 and SA‑6 batteries from nearly all of the regular known garrisons. The understandable reluctance of enemy SAM operators to emit and thus render themselves cooperative targets made them much harder to find and attack, forcing allied aircrews to remain constantly alert to the radar‑guided SAM threat throughout the air war.[222]It further had the effect of denying some high‑risk targets for a time, increasing force package size, and increasing overall SEAD sortie requirements.

Moreover, unlike in the more permissive Desert Storm operating environment, airspace availability limitations in the war zone typically made for high predictability on the part of attacking NATO aircraft, and collateral damage avoidance considerations frequently prevented the use of the most tactically advantageous attack headings. The resulting efforts to neutralize the Serb IADS were, according to retired U.S. Navy Admiral Leighton Smith, the commander of NATO forces in Bosnia from 1994 to 1996, “like digging out potatoes one at a time.”[223]The commander of USAFE, General Jumper, later added that the CAOC could never get NATO political clearance to attack the most troublesome early warning radars in Montenegro, which meant that the Serbs knew when attacks were coming most of the time.[224]In other cases, the cumbersome command and control arrangements and the need for prior CAOC approval before fleeting pop‑up IADS targets detected by Rivet Joint or other allied sensors could be attacked resulted in many lost opportunities and few hard kills of enemy SAM sites.

Operation Allied Force drew principally on 48 USAF F‑16CJs and 30 Navy and Marine Corps EA‑6B Prowlers, along with Navy F/A‑18s and German and Italian electronic‑combat role (ECR) Tornados, to conduct the suppression portion of allied counter‑SAM operations. Land‑based Marine EA‑6Bs were tied directly to attacking strike packages and typically provided ECM support for missions conducted by U.S. aircraft. Navy Prowlers aboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt supported carrier‑launched F‑14 and F/A‑18 raids and strike operations by allied fighters. The carrier‑based Prowlers each carried two AGM‑88 high‑speed antiradiation missiles (HARMs). Those operating out of Aviano, in contrast, almost never carried even a single HARM, preferring instead to load an extra fuel tank because of their longer route to target. This compromise was often compensated for by teaming the EA‑6B with HARM‑shooting F‑16CJs or Luftwaffe Tornado ECR variants.[225]

The USAF’s EC‑130 Compass Call electronic warfare aircraft was used to intercept and jam enemy voice communications, thereby allowing the EA‑6Bs to concentrate exclusively on jamming enemy early warning radars. The success of the latter efforts could be validated by the RC‑135 Rivet Joint ELINT aircraft, which orbited at a safe distance from the combat area. The biggest problem with the EA‑6B was its relatively slow flying speed, which prevented it from keeping up with ingressing strike aircraft and diminished its jamming effectiveness as a result. On occasion, the jamming of early warning radars forced Serb SAM operators to activate their fire‑control radars, which in turn rendered them susceptible to being attacked by a HARM. Accordingly, enemy activation of SAM fire‑control radars was limited so as to increase their survivability.[226]

SEAD operations conducted by F‑16CJs almost invariably entailed four‑ship formations. The spacing of the formations ensured that the first two aircraft in the flight were always looking at a threat area from one side and the other two were monitoring it from the opposite side. That enabled the aircraft’s HARM Targeting System (HTS), which only provided a 180‑degree field of view in the forward sector, to maintain 100‑percent sensor coverage of a target area whenever allied strike aircraft were attempting to bomb specific aim points within it. According to one squadron commander, the F‑16CJs would arrive in the target area ahead of the strikers and would build up the threat picture before the strikers got close, so that the latter could adjust their ingress routes accordingly. In so doing, the F‑16CJs would provide both the electronic order of battle and the air‑to‑air threat picture as necessary. The squadron commander added that enemy SAM operators got better at exploiting their systems at about the same rate that the F‑16CJ pilots did, resulting in a continuous “cat and mouse game” that made classic SAM kills “hard to come by.”[227]

As noted in Chapter Three, only a few SAMs were reported to have been launched against attacking NATO aircraft the first night. The second night, fewer than 10 SA‑6s were fired, with none scoring a hit. Later during Allied Force, enemy SAMs were frequently fired in large numbers, with dozens launched in salvo fashion on some nights but only a few launched on others. Although these ballistic launches constituted more a harassment factor than any serious challenge to NATO operations, numerous cases were reported of allied pilots being forced to jettison their fuel tanks, dispense chaff, and maneuver violently to evade enemy SAMs that were confirmed to be guiding.[228]

Indeed, the SAM threat to NATO’s aircrews was far more pronounced and harrowing than media coverage typically depicted, and aggressive jinking and countermaneuvering against airborne SAMs was frequently necessary whenever the Serbs sought to engage NATO aircraft. The Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, U.S. Army General Wesley Clark, later reported that there had been numerous instances of near‑misses involving enemy SAM launches against NATO aircraft, and General Jumper added that a simple look at cockpit display videotapes would show that “those duels were not trivial.”[229]From the very start of NATO’s air attacks, Serb air defenders also sought to sucker NATO aircrews down to lower altitudes so they could be brought within the lethal envelopes of widely proliferated MANPADS and AAA systems. A common Serb tactic was to fire on the last aircraft in a departing strike formation, perhaps on the presumption that those aircraft would be unprotected by other fighters, flown by less experienced pilots, and low on fuel, with a consequent limited latitude to countermaneuver.

The persistence of a credible SAM threat throughout the air war meant that NATO had to dedicate a larger‑than‑usual number of strike sorties to the SEAD mission to ensure reasonable freedom to operate in enemy airspace. In turn, fewer sorties were available for NATO mission planners to allocate against enemy military and infrastructure targets–although the limited number of approved targets at any one time tended to minimize the practical effects of that consequence. Moreover, the Block 50 F‑16CJ, which lacked the ability to carry the LANTIRN targeting pod, was never used for night precision bombing because it could not self‑designate targets.

One of the biggest problems to confront attacking NATO aircrews on defense‑suppression missions was target location. Because of Kosovo’s mountainous terrain, the moving target indicator (MTI) and SAR aboard the E‑8 Joint STARS could not detect objects of interest in interspersed valleys that were masked from view at oblique look angles, although sensors carried by the higher‑flying U‑2 often compensated for this shortfall.[230]The cover provided to enemy air defense assets by the interspersed mountains and valleys was a severe complicating factor. Similarly, efforts to attack the internetted communications links of the Yugoslav IADS were hampered by the latter’s extensive network of underground command sites, buried land lines, and mobile communications centers. Using what was called fused radar input, which allowed the acquisition and tracking of NATO aircraft from the north and the subsequent feeding of the resulting surveillance data to air defense radars in the south, this internetting enabled the southern sector operations center to cue defensive weapons (including shoulder‑fired man‑portable SAMs and AAA positions) at other locations in the country where there was no active radar nearby. That may have accounted, at least in part, for why the F‑16CJ and EA‑6B were often ineffective as SAM killers, since both employed the HARM to home in on enemy radars that normally operated in close proximity to SAM batteries.[231]

In all, well over half of the HARM shots taken by allied SEAD aircrews were preemptive targeting, or so‑called PET, shots, with a substantial number of these occurring in the immediate Belgrade area.[232]Many HARM shots, however, were reactive rather than preplanned, made in response to transitory radar emissions as they were detected.[233]

Yugoslavia’s poorly developed road network outside urban areas may also have worked to the benefit of NATO attackers on more than a few occasions because enemy SAM operators depended on road transportation for mobility and towed AAA tended to bog down when driven off prepared surfaces and into open terrain. NATO pilots therefore studiously avoided flying down roads and crossed them when necessary at 90‑degree angles to minimize their exposure time. By remaining at least 5 km from the nearest road, they often were able to negate the AAA threat, albeit at the cost of making it harder to spot moving military vehicles.

Whenever available intelligence permitted, the preferred offensive tactic entailed so‑called DEAD (destruction of enemy air defense) attacks aimed at achieving hard kills against enemy SAM sites using the Block 40 F‑16CG and F‑15E carrying LGBs, cluster bomb units (CBUs), and the powered AGM‑130, rather than merely suppressing SAM radar activity with the F‑16CJ and HARM.[234]For attempted DEAD attacks, F‑16CGs and F‑15Es would loiter near tankers orbiting over the Adriatic to be on call to roll in on any pop‑up SAM threats that might suddenly materialize.[235]The unpowered AGM‑154 Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW), a “near‑precision” glide weapon featuring inertial and GPS guidance and used by Navy F/A‑18s, was also effective on at least a few occasions against enemy acquisition and tracking radars using its combined‑effects submunitions.[236]

One problem with such DEAD attempts was that the data cycle time had to be short enough for the attackers to catch the emitting radars before they moved on to new locations. One informed report observed that supporting F‑16CJs were relatively ineffective in the reactive SEAD mode because the time required for them to detect an impending launch and get a timely HARM shot off to protect a striker invariably exceeded the flyout time of the SAM aimed at the targeted aircraft. As a result, whenever attacking fighters found themselves engaged by a SAM, they were pretty much on their own in defeating it. That suggested to at least some participating aircrews the value of having a few HARMs uploaded on selected aircraft in every strike package so that strikers could protect themselves as necessary without having to depend in every case on F‑16CJ or EA‑6B support.[237]

The commander of the Marine EA‑6B detachment at Aviano commented that there was no single‑solution tactic that allied SEAD assets could employ to negate enemy systems. “If we try to jam an emitter in the south,” he said, “there may be a northern one that can relay the information through a communications link and land line. They are fighting on their own turf and know where to hide.”[238]The detachment commander added that Serb SAM operators would periodically emit with their radars for 20 seconds, then shut down the radars to avoid swallowing a HARM.

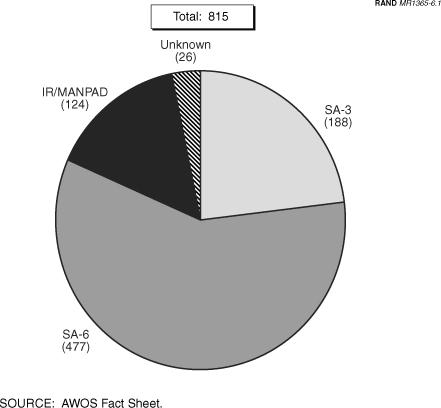

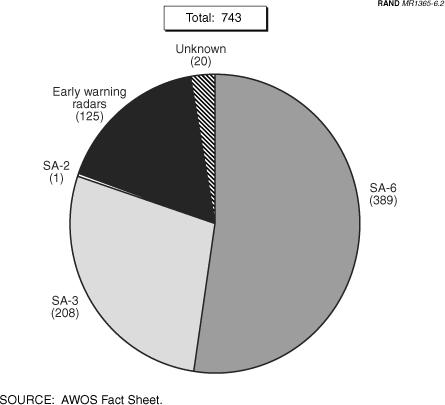

In all, more than 800 SAMs were reported to have been fired at NATO aircraft, both manned and unmanned, over the course of the 78‑day air war, including 477 SA‑6s and 124 confirmed man‑portable infrared missiles (see Figure 6.1 for a depiction of reported enemy SAM launches by type).[239]A majority of the fixed SAMs were fired without any radar guidance. Yet despite that expenditure of assets, only two NATO aircraft, an F‑117 and an F‑16, were shot down by enemy fire, although another F‑117 sustained light damage from a nearby SA‑3 detonation and two A‑10s were hit by enemy AAA fire but not downed.[240]There also were two reported cases of short‑range infrared (IR)‑guided missiles hitting A‑10s, one of which apparently struck the bottom of the aircraft, defused itself, and bounced off harmlessly.[241]At least 743 HARMs were fired by U.S. and NATO aircraft against the radars supporting these enemy SAMs (Figure 6.2 provides a detailed breakout of HARM expenditure by target type).[242]Yet enough of the Serb IADS remained intact to require NATO fighters to operate above the 15,000‑ft hard deck for most of the air effort. The main reason for this requirement was the persistent AAA and MANPADS threat. Although the older SA‑7 could be effectively countered by flares if it was seen in time, the SA‑9/13, SA‑14, SA‑16, and SA‑18 presented a more formidable threat.

Figure 6.1–Enemy SAM Launches Reported

Figure 6.2–HARM Expenditures by Target Type

In the end, as noted above, only two aircraft (both American) were brought down by enemy SAM fire, thanks to allied reliance on electronic jamming, the use of towed decoys, and countertactics to negate enemy surface‑to‑air defenses.[243]However, NATO never fully succeeded in neutralizing the Serb IADS, and NATO aircraft operating over Serbia and Kosovo were always within the engagement envelopes of enemy SA‑3 and SA‑6 missiles–envelopes that extended to as high as 50,000 ft. Because of that persistent threat, mission planners were forced to place such high‑value ISR platforms as the U‑2 and Joint STARS in less‑than‑ideal orbits to keep them outside the lethal reach of enemy SAMs. Even during the operation’s final week, NATO spokesmen conceded that only three of Serbia’s approximately 25 known mobile SA‑6 batteries had been confirmed destroyed.[244]

In all events, by remaining dispersed and mobile, and activating their radars only selectively, the Serb IADS operators yielded the short‑term tactical initiative in order to present a longer‑term operational and strategic challenge to allied air operations. The downside of that inactivity for NATO was that opportunities to employ the classic Wild Weasel tactic of attacking enemy SAM radars with HARMs while SAMs were guiding on airborne targets were “few and far between.”[245]The Allied Force air commander, USAF Lieutenant General Michael Short, later indicated that his aircrews were ready for a wall‑to‑wall SAM threat like that encountered over Iraq during Desert Storm, but that “it just never materialized. And then it began to dawn on us that… they were going to try to survive as opposed to being willing to die to shoot down an airplane.”[246]In fact, the survival tactics employed by Serb IADS operators were first developed and applied by their Iraqi counterparts in the no‑fly zones of Iraq that have been steadily policed by Operations Northern and Southern Watch ever since the allied coalition showed its capability against active SAM radars during the Gulf war. That should not have come as any great surprise to NATO planners, and it is reasonable to expect more of the same as potential future adversaries continue to monitor U.S. SEAD capabilities and operating procedures and to adapt their countertactics accordingly.

The dearth of enemy radar‑guided SAM activity may also have been explainable, at least in part, by reports that the Air Force’s Air Combat Command had been conducting information operations by inserting viruses and deceptive communications into the enemy’s computer system and microwave net.[247]Although it is unlikely that U.S. information operators were able to insert malicious code into enemy SAM radars themselves, General Jumper later confirmed that Operation Allied Force had seen the first use of offensive computer warfare as a precision weapon in connection with broader U.S. information operations against enemy defenses. As he put it, “we did more information warfare in this conflict than we have ever done before, and we proved the potential of it.” Jumper added that although information operations remained a highly classified and compartmented subject about which little could be said, the Kosovo experience suggested that “instead of sitting and talking about great big large pods that bash electrons, we should be talking about microchips that manipulate electrons and get into the heart and soul of systems like the SA‑10 or the SA‑12 and tell it that it is a refrigerator and not a radar.”[248]Such pioneering attempts at offensive cyberwarfare pointed toward the feasibility of taking down SAM and other defense systems in ways that would not require putting a strike package or a HARM missile on critical nodes to neutralize them.

During Desert Storm, by means of computer penetration, high‑speed decrypting algorithms, and taps on land lines passing through friendly countries, the United States was reportedly able to intercept and monitor Iraqi email and digitized messages but engaged in no manipulation of enemy computers. During Allied Force, however, information operators were said to have succeeded in putting false targets into the enemy’s air defense computers to match what enemy controllers were predisposed to believe. Such activities also reportedly occasioned the classic operator‑versus‑intelligence conundrum from time to time, in which intelligence collectors sought to preserve enemy threat systems that were providing them with streams of information while operators sought to attack them and render them useless in order to protect allied aircrews.[249]

Fortunately for NATO, the Serb IADS did not include the latest‑generation SAM equipment currently available on the international arms market. There were early unsubstantiated reports, repeatedly denied by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that several weeks before the start of the bombing effort, Russia had provided Yugoslavia with elements of between six and ten S‑300PM (NATO code‑name SA‑10) long‑range SAM systems, which had been delivered without their 36D6 Clam Shell low‑altitude acquisition radars.[250]Had those reports been valid, even the suspected presence of SA‑10 and SA‑12 SAMs in the enemy IADS inventory would have made life far more challenging for attacking NATO aircrews. Milosevic reportedly pressed the Russians hard for such equipment repeatedly, without success. Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott later stated that the Yeltsin government had been put on the firmest notice by the Clinton administration that any provision of such cutting‑edge defensive equipment to Yugoslavia would have had a “devastating” effect on Russian‑American relations.[251]

All of this raised basic questions about the adequacy of U.S. SEAD tactics and suggested a need for better real‑time intelligence on mobile enemy IADS assets and a means of getting that information to pilots quickly enough for them to act on it, as well as for greater standoff attack capability.[252]The downings of both the F‑117 and F‑16 were attributed to breakdowns in procedures aimed at detecting enemy IADS threats in a sufficiently timely manner and ensuring that pilots did not fly into lethal SAM envelopes unaware of them. Other factors cited in the two aircraft downings were faulty mission planning and an improper use of available technology (see below for more on the F‑117 downing). Although far fewer aircraft were lost during Allied Force than had been expected, these instances pointed up some systemic problems in need of fixing. As one Air Force general observed, “there had to be about 10 things that didn’t go right. But the central issue is an overall lack of preparedness for electronic warfare.”[253]

One of the first signs of this insidious trend cropped up as far back as August 1990, when half of the Air Force’s ECM pods being readied for deployment to the Arabian peninsula for Desert Storm were found to have been in need of calibration or repair. Among numerous later sins of neglect with respect to electronic warfare (EW) were Air Force decisions to make operational readiness inspections (ORIs) and Green Flag EW training exercises less demanding, decisions that naturally resulted in an atrophying of the readiness inspection and reporting of EW units, along with a steady erosion of EW experience at the squadron level. “Now,” said the Air Force general cited above, “they only practice reprogramming [of radar warning receivers] at the national level. Intelligence goes to the scientists and says the signal has changed. Then the scientists figure out the change for the [ECM] pod and that’s it. Nobody ever burns a new bite down at the wing.”[254]

During the years since Desert Storm, the response time for SEAD challenges has become longer, not shorter, owing to an absence of adequate planning and to the disappearance of a talent pool of Air Force leaders skilled in EW. One senior Air Force Gulf War veteran complained that “we used to have an XOE [operational electronic warfare] branch in the Air Staff. That doesn’t exist any more. We used to reprogram [ECM] pods within the wings. They don’t really do that any more.” During a subsequent colloquium on the air war and its implications, former Air Force chief of staff General Michael Dugan attributed these problems to the Air Force’s having dropped the ball badly in 1990, when it failed to “replace a couple of senior officers in the acquisition and operations community who [oversaw] the contribution of electronic combat to warfighting output. The natural consequence was for this resource to go away.”[255]

A particular concern prompted by the less‑than‑reassuring SEAD experience in Allied Force was the need for better capabilities for accommodating noncooperative enemy air defenses and, more specifically, countering the enemy tactic whereby Serb SAM operators resorted to passive electro‑optical rather than active radar tracking. That tactic prompted Major General Dennis Haines, Air Combat Command’s director of combat weapons systems, to spotlight the need for capabilities other than relying on radar emissions to detect SAM batteries, as well as to locate and fix on enemy SAM sites more rapidly when they emitted only briefly.[256]Looking farther downstream, one might also suggest that in the long run, the answer is not to continue getting better at SEAD but rather to move to improved low‑observability capabilities and to the use of UCAVs (unmanned combat air vehicles), with a view toward rendering SEAD increasingly unnecessary.

Such concerns have occasioned a growing sense among SEAD specialists that the management of EW should be taken out of the domain of information operations, where it was pigeonholed for convenience after the retirement of the EF‑111 and F‑4G, and returned to its proper home at the USAF Air Warfare Center at Nellis AFB, Nevada. As one senior officer complained in this respect, electronic combat after Desert Storm found itself “buried in with information operations and information attack. What got lost was the critical issue that EW is a component of combat aircraft survivability.”[257]One side result of this neglect of the EW mission by the Air Force was that maintenance technicians could no longer reprogram quickly (that is, in 24 hours or less) ECM pods and radar warning receivers to counter newly detected enemy threats. That problem first arose in 1998, when several planned U‑2 penetrations into hostile airspace had to be canceled at the last minute because USAF radar warning systems could not recognize some IADS signals emanating from Iraq and Bosnia.

Yet another problem highlighted by the IADS challenge presented in Allied Force was the disconcertingly small number of F‑16CJs and EA‑6Bs available to perform the SEAD mission. Aircraft and aircrews were both stretched extremely thin, even with the modest help provided by German and Italian Tornado ECR variants. This shortage of SEAD assets prompted a proposal for backfitting the HARM targeting system carried by the F‑16CJ onto older F‑16s and F‑15Es. Another fix suggested for the shortfall in SEAD capability was to begin supplementing existing capabilities and tactics, which rely on the small‑warhead HARM, with PGMs and attack tactics aimed at achieving hard kills against IADS targets for the duration of a campaign, essentially a very different approach. Most telling of all, the uneven results of the SEAD experience in Allied Force induced Air Combat Command to seek an increase in its planned acquisition of new F‑16CJs from 30 to 100.[258]

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1218;