THE EIGHTH CONTINENT

Sailing the Great Pacific Garbage Patch

In my sleep, I heard the call. All hands. Someone had shouted it into our cabin. All hands to strike sail. We fell out of our bunks, struggled into our rain gear, and went above half‑awake.

The deck was a starless uproar of wind and sound. “The Navy’s running an exercise nearby,” said the first mate. “They’ve ordered us to head north. I asked them to let us run downwind, but they just repeated the order.” The ship, under engine power, was running directly into the wind, the sails flapping powerless and wild. They would be torn to shreds.

We wrestled the foresails in the dark. The air filled with spray, with thick rope jerking and snapping in chaos. There were six of us in the bow. Four were out on the bowsprit–the long spar extending forward over the water–and two on the most forward part of the deck, where the bowsprit joined the ship.

I was on the deck, feeling with my hands in the dark, trying to find the downhaul lines and gaskets that would draw down and fasten the sails. After weeks at sea, I knew what I was looking for, but that didn’t mean I could find it.

The ship crested a large wave. We felt the bow rise higher and higher into the night. It seemed to pause at the top. For a moment we floated in the salty air.

Then we fell. The ship buried its prow in the oncoming wave, deeper than ever before. The four on the bowsprit–my friends–disappeared below the surface, foam churning over their heads. Were they clipped in? The deck went under with them. The water surged to my waist, tugging at me, sliding me aft. Robin grabbed my arm and I grabbed the rail, and we kept ourselves from tumbling backward down the deck. I looked at the bowsprit and thought, All I see is foam.

A second more and the ship came through, rising out of the swell, and I saw them. They were still there, still clutching the bowsprit, all four of them. I counted them again. Four. Had there been more?

“Is everybody there?” I shouted. “Is everyone still on board?”

But they were already working again, grappling the sails, water streaming from their jackets, shrieking like bull riders.

Robin let go and we returned to the tangle of lines at our feet. But my head was swimming with the afterimage of the water rising up to us, of the sea invading the deck. I still felt it, how it pulled at my body, an overwhelming force that swirled around and through us, the alien gravity of another universe, the black remorseless ocean.

You will have heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch: an island of trash, formed by a giant vortex of currents that gathers all the eternal, floating plastic in the northern half of the Pacific Ocean into an endless, swirling purgatory, a self‑assembling plastic continent twice the size of Texas.

Let’s nip this in the bud: It’s not an island.

I’d like to say that again. It’s not. An island.

There is no solid mass, no floating carpet of trash, no landfill. But it is real. It was first discovered in 1997 by the yachtsman and environmentalist Charles Moore, who made it the focus of his nonprofit, the Algalita Marine Research Foundation. It is thanks to Moore’s observations that the Pacific Garbage Patch entered the popular consciousness, sometime in the mid‑2000s. As for who’s responsible for the irresistible image of a plastic island, I don’t know. But someone should run them down and give them a nice, quick smack. Furthermore, an exorbitant fine should be levied on anyone–anyone –who describes this non‑island as being “the size of Texas” or “twice the size of Texas.” When I was doing my preliminary research, it seemed impossible to find a piece of media about the garbage patch that didn’t mention Texas.

Why Texas? Is there no other territory that could serve as a reader‑friendly reference point? Has hack journalism become so impoverished an art form that its practitioners can’t even be troubled with the five googling seconds it would take to craft an entirely original gem like “three times the size of California,” or “two Nevadas and an Arizona,” or “nearly as big as Alaska, if you leave out the Aleutians”?

The real problem is that, although two Texases clear a trim half‑million square miles, nobody knows how large the Garbage Patch actually is. Unlike Texas and, critically, unlike an island, it has no defined boundary, only a general area. So let’s just call it big, and be done with it.

A more appropriate analogy would be that of an ecosystem. System is the key here, implying something much more complex than a simple floating object. From tuna‑size hunks of Styrofoam and discarded fishing nets that lurk like massive jellyfish, down to microscopic pellets that hang in the water like artificial plankton, it is a vast, plastic simulacrum of the living ocean that is its host. And precisely because it is so complex, and so far from land, its nature is poorly understood.

Nobody can say for sure exactly where all the stuff comes from, but there is broad agreement that its sources are disproportionately land‑based. A surprising amount of trash manages to avoid the landfill, and when it does, it often makes its way to the sea, whether by way of storm drains, rivers, or other avenues.

Since plastic objects don’t degrade easily, if ever, they have plenty of time to work their way out from land and find the ocean’s currents. A plastic bottle taken by the currents off San Francisco will travel south as it heads out into the Pacific, passing through the latitudes of Mexico and even Guatemala before heading west in earnest, caught by the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. This vast counterclockwise vortex will take the bottle clear across to the Philippines before shooting it north toward Taiwan, close by Japan, and then spitting it back past Alaska, toward the rest of North America.

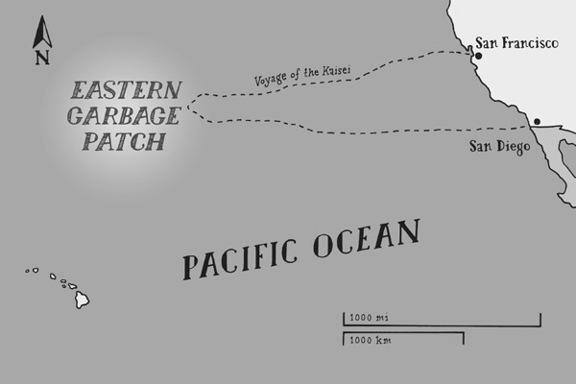

Around and around the Gyre goes, and the plastic bottles and hard hats of the North Pacific go with it, we assume, until at last they drift into the becalmed zones spinning at the eastern and western ends of this oceanic conveyor belt. These are the Eastern and Western Garbage Patches. (The Eastern gets all the attention because it’s closer to the United States and was the first to be discovered.) Here, our plastic bottle finds its friends: all the other bits and pieces of plastic that have made it into the ocean in the previous who‑knows‑how‑long. And here they wait, year upon year, breaking into fragments from the action of the waves, and strangling hapless turtles, choking overzealous albatross that mistake plastic for food, and being eaten by fish.

Eventually, the scientists and the activists and the adventurers come. Whatever part of our plastic history that floats, the Garbage Patch is the place for them to find it: our bottles, our plastic tarps, our popped bubble wrap, the tiny plastic “scrubbing beads” of our exfoliating face soap. It’s all here for the hunting.

Or so I hoped. But without a single cruise line running through, how was I to know for sure? Which brings us to another interesting thing about the Garbage Patch: hardly anyone has actually seen it. It takes serious oceangoing chops to get out there. And there’s almost no reason anyone with a boat would bother. Most people with yachts and things are more interested in going to places like Hawaii, or the Bahamas, or anywhere. But the Garbage Patch, inherent to its formation, is in the middle of the biggest nowhere on the planet.

The Gyre had seen several expeditions from researchers and activists the previous summer, in 2009, so I took to the phones, beginning a campaign of sustained pestering that I hoped would be my ticket onto one of this year’s voyages. And that’s how I met Project Kaisei.

I found the Kaisei docked in Point Richmond, across the bay from San Francisco. A steel‑hulled, square‑rigged, 150‑foot‑long brigantine, it was a striking sight. Think metal pirate ship and you will have the image. The ship is the namesake and floating linchpin of Project Kaisei, a nonprofit venture dedicated, as its motto reads, to “Capturing the plastic vortex.” I had somehow convinced Mary Crowley, one of its founders, to let me come along on a three‑week voyage to that plastic vortex, a thousand miles away, but I had my doubts about capturing it.

Especially if we never left. We had spent more than a week without a clear sense of when we might set out to sea. A departure day would be announced, only to dawn with the new radar unit still absent, or with provisions yet to be delivered, or with a cook not yet hired, and we would not sail.

In the meantime, a subset of the crew would show up each day to help clean the boat, patch its rust holes, touch up the blue paint on the hull, or install an extra life raft, and I had time to develop my mixed feelings about the Kaisei. From the moment I first stepped aboard, I had tasted that flavor of excitement that has a note of terror. She had two great masts, the forward one boasting four spars: the yards, from which majestic square sails would drape, sails that belonged in a biography of Lord Nelson. Dozen upon dozen of cables and ropes–lines, we learned, not ropes but lines –led from wooden pins on the deck to points above; this set of lines to pull a sail down, that to pull it up; lines to orient the yards to starboard or to port; lines to raise and lower the spar of the gaff sail; lines to raise and lower sets of pulleys that were connected to still further lines.

Was I going to be asked to climb those masts, to edge out along those yards, approximately a thousand feet up? Like most sensible people, I don’t really have a fear of heights–only a fear of falling to my death. Which is not a fear at all, but a sensible attitude. On the other hand, what is the point of being on a tall ship if you don’t experience the tallness? I knew that when asked to go aloft, I would overcome or at least bypass my fear and force myself to do it. And so what I really feared was that I wasn’t afraid enough.

This was all neatly analogous to my broader situation: instead of a nice, short jaunt on a press boat or a proper research vessel, I was going to sea for three weeks or more. A thousand miles from land when I wanted to be at home in New York, when I should have been at home, squaring away wedding plans, preparing for the moment of my good fortune, only two months away, when the Doctor and I would get hitched. And the Kaisei would be sailing in total seaborne isolation. There would be no satellite phone for the crew, no data connection, no way to communicate with my family or with the Doctor. No way even to apologize, once I went, for being gone.

The ship itself was charming, if a bit scruffy, with cabins that were cozy but not claustrophobic, and a pair of lounges ample for a small crew, and decks of faded wood. In front of the wheelhouse, with its radio and its radar display, was an outdoor bridge, where the deck rose into a platform facing a large, spoked wheel. It was the kind of wheel I would have expected to see on the wall of a nautical‑themed restaurant.

The problem was not the Kaisei. The problem was us. As the days went by, spent in sanding and painting and offloading unneeded scientific equipment from the previous year’s voyage, I met the volunteers who would be the crew. How many people did it take to sail a 150‑foot brigantine? I wasn’t sure we yet had ten. And as we got to know one another, it emerged that very few of us knew anything that would be useful in the safe operation of said brigantine.

There was Kaniela, for instance, an affable young surfer from Hawaii and one of the hardest workers on the boat. He asked me if I knew much about sailing.

I didn’t, I said. Not a thing. You?

Nah, man. I’m hoping to learn.

Then there were Gabe and Henry, two recently graduated Oberlin hipsters. The morning we met, they were standing on deck huddled against the early chill, hands stuffed in their pockets, wearing their sunglasses. A surly pair, I thought, but they turned out just to be badly hung over, and had brightened up by mid‑afternoon. They told me they both had degrees, more or less, in environmental studies, or something. Upon moving back to Marin County from Oberlin, they had gotten internships at the Ocean Voyages Institute, the umbrella organization for Project Kaisei. But three weeks at sea seemed a little extreme for an internship. I asked them why they were coming.

With a straight face, Gabe told me that he was here for the adventure. He wanted to be an adventurer. A rakish rogue, he specified. And this was the first step toward his goal.

The ravings of a contaminated mind. I turned to Henry. I asked him if either of them knew how to sail.

He smiled. It was a thin smile, similar to a wince. They had taken sailing in high school, he said. Little two‑person boats.

What was that feeling in my gullet? Desperation? I made my way from volunteer to volunteer, making a mental map of our skill set. We had a deep bench in watersports and the teaching of high school science. Otherwise, it was a mixed bag. There was a boatbuilder, a former journalist, a few students. They were all interesting, thoughtful, hardworking people who didn’t know a damn thing about sailing a tall ship.

I put my hope in the second mate, a calm, confident tall‑ship sailor…who quit. After a single afternoon on board, he told the captain he didn’t like the look of things and got the hell out of there.

There it was again. That sinking feeling.

The votes of ill‑confidence started to pile up. A team of Coast Guard bluesuits came to inspect the boat’s papers. As they left, chuckling, I heard the Kaisei ’s captain say, “They’d never seen anything like this.”

The more I learned about the Kaisei, the more I realized that, from a technical point of view, she was an oddity. One evening I sat on the aft deck with the ship’s engineer, watching Richmond’s tugboats go by and listening to him complain. The engineer was probably the most important person in the crew, if it mattered to us that the ship remain afloat, that we have fresh water, and that the navigational gear function. Night after night, he had been up late, coaxing the ship’s systems into fighting shape. He was grumpy, but that seemed like a good sign. You don’t want a laissez‑faire engineer.

The Kaisei, he told me with some exasperation, had been built in Poland, only to be refitted and operated in Japan. Everything was in Polish and Japanese. And the electricity. He shook his head. Multiple standards, in a dazzling range of voltages. The irregularity extended literally to the nuts and bolts of the ship: some were metric, some weren’t, and so multiple sets of tools were required, though none of the multiple sets on board were complete.

The engineer sipped from his mug and let out a great sigh. “Excuse me,” he said. “I’m into my cup.”

Within a few days, he, too, had quit.

We now had no second mate, and no engineer, and none of us lowly volunteers–the crew–knew what the hell was going on. Every day of delay was shortening the mission: in barely three weeks, the Kaisei was booked to participate in the San Diego Festival of Sail, where we would blow the minds of all those tall‑ship enthusiasts with our adventures in deep ocean plastics. So every day tied up at the dock was a day we didn’t spend in the Gyre. We began to doubt that the boat would ever leave the dock. And with experienced crew members disappearing by the day, the rank and file were wondering if we, too, should step off the boat.

Something held us back, though. Something that counterbalanced all the bad omens. A single factor that kept the entire crew from walking.

It was the Pirate King. His name was Stephen, and his position was first mate, but I thought of him as the Pirate King of the Kaisei, a single person so compulsively knowledgeable about seafaring that he made up for the frightening deficits in the rest of us. A compact man, even short, he was trim and strong, with a close beard and two golden hoops in his left ear, and just in case we weren’t paying attention, he wore a black baseball cap decorated with a skull and crossbones.

The Kaisei had a captain, but we mostly ignored him in deference to the Pirate King, who exemplified that very specific kind of manhood that is built on overwhelming knowledge. He knew how to navigate, how to tie knots, how to rig a sailboat, how to walk along the yards with barely a hand to hold himself in place, and how to slide down the stays, Douglas Fairbanks‑like, landing himself back on deck in mere seconds. He never wore a safety harness. He knew how to furrow his brow and raise his voice and tell us that, as first mate, he was responsible for us. He had personally circumnavigated the globe in his own small sailboat at near‑racing pace, sailing through every kind of sea imaginable, even surviving a rogue wave. He was equal parts Jack Sparrow and Han Solo, and we would have followed him anywhere–across the Pacific in a rowboat, up Everest in our shorts, suitless through an airlock into deep space–as long as he was there to tell us what to do. You can actually survive in deep space without a space suit, he would have explained. You just need to control your exhalations.

He promised us he would walk off the boat if it wasn’t safe, and that was good enough for us. He became our knot‑tying, aggressively all‑knowing weathervane. And sure enough, a new engineer was found, and a cook, and everything came together at the last minute, and finally, eventually, suddenly–we sailed.

The crew of a ship about to go out of range becomes diligent with its telephones. I texted my friends and family and posted a picture from the far side of the Golden Gate Bridge. I received one, too: my friend Victoria had gone up on the Marin Headlands to take a picture as we left. On the boat, we looked at it, the picture of ourselves. It showed the mouth of the bay, opening out from the land of the Golden Gate. Our ship was in the center of the picture, our huge steel ship, barely a dozen pixels wide, the merest smudge against the sky‑colored sea.

And I talked to the Doctor one last time. She made me promise her something. She made me promise that if I found myself being washed off the ship, I would hang on.

“Promise,” she said. “Promise you’ll hang on with your last fingernail.”

Conversations about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch tend to follow a certain profile. First there is the flash of recognition, embedded with a nugget of misinformation:

Right! The giant plastic island! The one the size of Texas!

It’s not an island, you say.

Well, right, they say, moderating. It’s more of a pile.

You narrow your eyes. Seriously, how do you pile anything on the ocean?

Eventually, with coaxing, they let go of the island imagery, of impractical notions of how things pile, of Texas. Sobriety achieved, there comes the inevitable question:

Can it be cleaned up?

A lot of people have considered this question, and have debated it, and have pondered different strategies and possibilities. From this, a broad consensus has emerged among scientists and environmentalists, which I’m happy to summarize:

Get real.

We’re talking about the ocean here. Even assuming that we could just get a big net–whoever we is–and that it would be worth the massive use of fuel to drag it back and forth for thousands of miles across the Gyre, and that there would be an exit strategy for what to do with a hemisphere‑size net full of trash…even granted all these impossibilities, there remains the intractable fact of the confetti.

As a plastic object spends year after year in the water, it becomes brittle from the sun. The waves begin to break it into pieces, and gradually it is delivered into smaller and smaller bits, a plastic confetti that might be the most troublesome thing about the Garbage Patch. Nets and larger objects may strangle marine life, and bottle caps and disposable cutlery may fill the stomachs of baby albatross, but the confetti has a chance of interacting with the ecosystem at a more fundamental level. Since it is consumed just as food would be, it has the potential to introduce toxins at the bottom of the food chain, toxins that may be concentrated by their passage up the chain to large animals like tuna and humans. In 2009, researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (on a voyage funded in part by Project Kaisei) found plastic in the stomachs of nearly a tenth of all the fish they sampled in the Garbage Patch, and they estimated that tens of thousands of tons of plastic are consumed by fish there every year.

This is a lot like what happened in Chernobyl, where radionuclides followed the same pathways as nutrients to become incorporated into vegetation, and presumably animals. As the journalist and author Mary Mycio has written, in Chernobyl “radiation is no longer ‘on’ the zone, but ‘of’ the zone.” Perhaps we can already say the same of plastic in the oceans. It is not only a fact of life, but part of it.

How then to clean it up? To remove a billion large and tiny pieces of the ocean from itself? A cosmic coffee filter? And then, how to avoid also straining out every whale and minnow in the sea, every sprite of plankton?

It was no surprise, then, to find that organizations devoted to this issue tended to avoid the idea of cleanup. Charles Moore’s Algalita Marine Research Foundation, a leader in the budding field of Garbage Patch studies, has a bent for “citizen science” that hearkens back to science’s roots as a discipline founded by amateurs. Rather than speculate about cleanup, it produces peer‑reviewed research for journals like the Marine Pollution Bulletin. Moore has been openly scornful of the idea of cleaning up marine plastic. Appearing on the Late Show with David Letterman, he swatted down his host’s hopeful questions about cleanup. “Snowball’s chance in hell,” he said. (Letterman told Moore his outlook seemed “bleak” and proposed they get a drink.) Other organizations focus on finding garbage patches in the other ocean gyres of the world or on raising awareness to combat the overuse of plastic on land.

So Project Kaisei is special. “Capturing the plastic vortex” is more than its motto. It’s a succinct mission statement. Not content to tilt at the windmill of keeping plastics out of the ocean in the first place, Kaisei has chosen to go after the biggest windmill of them all: finding some way to clean them up.

The force behind Project Kaisei is Mary Crowley, a toothy woman in late middle age with a warm smile and an unshakable belief in the possibilities of marine debris cleanup. She has gone so far as to envision ocean‑borne plastic retrieval as an actual industry. “Fishing for plastics, so to speak, is not that different from fishing for fish,” she told me, leaning on the Kaisei ’s starboard rail. “And unfortunately, we’ve so overfished the oceans. I think it would be a wonderful employment for fishermen to be able to get involved in ocean cleanup, and give fish a chance to have a healthier environment and restock.”

We can only hope that one day the fishing industry will be rescued by fishing for plastic instead of actual fish. (Indeed, a proposal to subsidize fishermen for debris pickup has even been floated in the EU.) In any case, let’s state for the record that in the early‑twenty‑first century, when most people said cleanup was impossible, Project Kaisei kept the dream alive. May they be proven prescient.

This summer’s mission, though, had been shrinking in scope almost since it was conceived. There had originally been plans for two trips, in quick succession, as well as a short press voyage that would depart from Hawaii to rendezvous with the Kaisei in the Garbage Patch. Mary had even spoken to me of tugging a barge out to the Gyre, of recruiting fishing boats to help retrieve mass quantities of refuse.

Those ideas had evaporated, and the scope of the mission had narrowed. The goal of the voyage now, Mary told me, was to use ocean‑current models being developed by scientists at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and at the University of Hawaii to pinpoint the areas with the largest plastic accumulation. By comparing our observations with the scientists’ models, it would be possible to devise effective ways of finding the plastic, a critical precondition for future cleanup. Think of it as fisheries research for the seaborne trash collectors of tomorrow.

She said we would also be “working on the most effective ways to use commercial ships–tugs, barges, fishing boats–to do actual collection,” or, as a Project Kaisei press release put it, “further testing collection technologies to remove the variety of plastic debris from the ocean.”

The word further alludes to the Kaisei ’s voyage of the previous summer. I heard many references to the technology developed as part of that voyage, specifically “the Beach,” a device designed to answer the intractable problem of the confetti. Passively powered by wave motion, the Beach allowed water to run over its surface, I was told, capturing the plastic confetti without the need for impractical filtering, and without catching marine life as well.

As the Golden Gate Bridge sank into the ocean behind us, Mary explained her position. She said it simply wasn’t enough to talk about stemming the flow of plastic from land. Even if we stopped the influx from the United States, there would still be plastic from the rest of the world getting into the oceans. And she had spent her entire life on and around the ocean, building a successful sail‑charter business. The ocean was her life’s work. She felt she had to do something.

“So we have to work very vigorously to stop the flow,” she said. “But we also have to effect cleanup.”

Was that so wrong?

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 1250;