Forcing the stay

We begin to work seriously on the down stay only after the dog lies down quickly and eagerly on command. Teaching the down stay involves physical punishment. We will be obliged to make use of compulsion in order to make the “Stay!” command a strong and vivid one for the dog.

We begin by concentrating on the “break” itself, the act of rising from the down without permission. By standing near the dog on the correction leash the handler can punish the animal as soon as it stirs with a quick jerk on the leash and a “No!”–making crystal clear to it that it must not move from the down.

We proof the stay by putting the dog down in very distracting or stimulating circumstances (among a group of other dogs running free, for example). The handler remains near the dog and watches it closely, ready to correct it in the act of getting up.

Sooner or later the handler will have to walk away from his dog and out of sight. With the dog all alone on the field like this and off leash, the context of the exercise will be completely different. Provided with some enticing distraction, like a ball thrown for another dog, the animal will be sure to break the stay at least once. Of course, when it does, it is impossible to catch it in the act. We will instead be forced to punish it after the fact.

The handler does so calmly and quietly. He does not scream with anger and run at the dog to take vengeance upon it. This is neither necessary nor advantageous. By charging at the animal we risk frightening it and making it shy away from us. Above all, we risk teaching it to run away in order to avoid correction. If the dog learns to wait until its handler leaves it and then breaks the down stay and runs about the field, avoiding anyone who might catch and correct it, then we will have created a serious training problem for ourselves.

Instead the handler sharply tells the dog “No!” at the instant that it gets up from the down, in order to mark for the animal the exact moment where it went wrong. Then he strides calmly over to the dog and lays hold of it by the scruff of the neck forcefully but not violently, drags it bodily all the way back to the spot it was left to stay and mashes it back into the down, taking little care for the dog’s comfort or dignity in the process. He then lets go of the animal, turns on his heel and walks away again. During the entire procedure, he says only two words: “No!” when the dog gets up, and “Stay!” as he turns the animal loose after the correction.

The correction itself, while unpleasant for the animal, is not violent or vengeful. The handler depends upon persistence rather than retribution to convince the dog that it is in its best interests to stay where it is left. As many times as the dog breaks, the handler calmly and forcefully drags it back and mashes it down, a little more harshly each time. Eventually the animal will give up and hold the down stay in spite of the distractions we offer it, and then the handler goes to it and praises it.

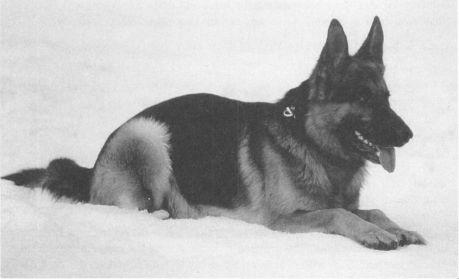

For the long down the dog must be calm and rock‑steady (and sound under gunfire). (Howard Glicksman’s V Igor von Noebachtal, Schutzhund III, FH.)

The handler uses a piece of food in the right hand to lead the animal into a stand.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 952;