INDUCIVE TRAINING VERSUS COMPULSIVE TRAINING

In the past it always was (and often still is) taken for granted that some sort of physical force is required in order to train a dog. Therefore, traditional dog training was almost wholly compulsive in nature.

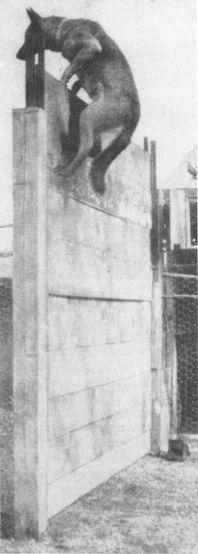

The A‑frame climbing wall seen in today’s Schutzhund trials is a comparatively recent invention. In von Stephanitz’s time, the obstacle was vertical. This dog scales the wall at seven feet, six inches. (From von Stephanitz, The German Shepherd Dog , 1923.)

It is in heeling or jumping that championships are often won or lost.

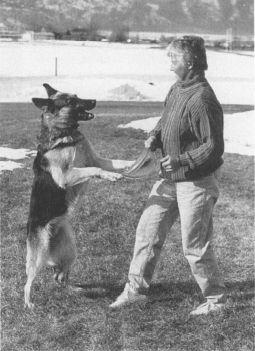

Our basic method of motivating the animal is to associate prey arousal with obedience, so that the exercises are infused with its energy. (Barbara Valente and “Mucke,” Schutzhund I.)

Compulsive training punishes and rewards the animal through the use of unpleasant stimuli. The handler punishes the dog by presenting it with something unpleasant. For example, if the animal breaks a down stay, it is corrected with a slap of the leash on its withers. The handler rewards the dog by taking away or omitting something that is unpleasant for it. For example, he shows the dumbbell to the dog, begins pinching the animal’s ear and stops pinching only when the animal takes the dumbbell into its mouth.

Traditional dog training depends upon physically manipulating the animal, and this is why traditional methods are inseparable from the use of a leash. Only comparatively recently have some trainers thrown away their leashes and discovered another way to train, an inducive way.

Inducive training punishes and rewards the animal through the use of pleasant stimuli. The handler rewards the dog by presenting it with something that is pleasant. For example, he praises the animal, gives it a piece of food, or even throws the ball for it when it performs a correct, fast finish. The handler punishes the dog by taking away or omitting something that is pleasant for it. For example, he punishes a crooked come‑fore by refusing to praise or feed the dog, or throw the ball for it.

Of course, in actual practice, the distinction between compulsive and inducive methods is often blurred. For instance, the distinction is unclear when the “force” used to compel the dog is very gentle, as when a handler guides a puppy into a sit with his hands and the leash. This procedure is not easily construed as unpleasant. It is also unclear when, as is customary, the handler corrects or punishes his dog, and then immediately praises and pets it a moment later. In this case we would seem to combine the two different kinds of training.

We can make the distinction in another way by examining the issue of choice, or free will. In inducive training the animal is free to choose what it will do. When told to sit, it is at liberty to instead lie down, stand or run in circles. The only constraint on its behavior is that we will reward only a sit, and all other responses will be punished by omitting the reward. In compulsive training, the dog has no choice and no free will. There is only one response possible for it. All others will be corrected–forcibly stopped before they can be gotten underway. This is what the leash is all about, and why traditional training methods have for so many years been dependent upon it or some other method of restricting the animal’s freedom of choice.

In the last ten years or so this country has seen a revolution of sorts, a movement toward inducive training. It is difficult to say why it occurred so recently, because the inducive aspect of animal training was already well understood by behavioral scientists in the 1960s and even earlier.

The inducive revolution was undoubtedly influenced by the appearance of academically educated dog trainers who make a profession of helping owners of pets with behavioral problems. These behavioral therapists, as they are called, primarily use inducive techniques and normally disapprove of compulsion.

Events far from the world of working dogs may have played a role in the inducive revolution as well. In the last two decades commercial marine mammal training facilities such as Sea World have gained tremendous prominence. The trainers at these facilities have mastered a very high form of the art of inducive training. In marine mammal training, inducive expertise is a necessity because a dolphin deep in its tank has nearly unlimited freedom of choice. It is impractical, and many people believe unethical, to try to compel it to do anything. All that remains is to reward it when the animal does as desired and omit reward when it does not. Some of these experts in inducive technique have crossed over to the world of dog training, most notably Karen Pryor.

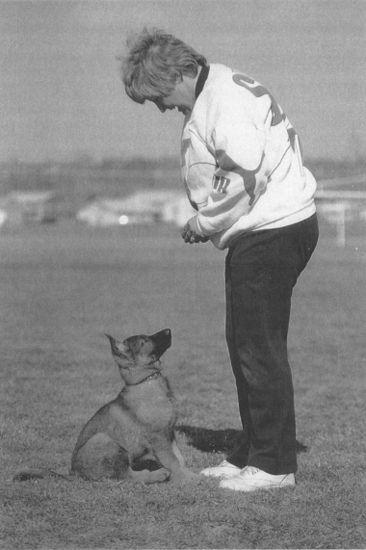

Inducive techniques are used, above all, in training puppies. (Susan Barwig with “Quella.”)

Inducive technique came on the scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s. A small group of people immediately embraced it. Old‑time “snatch‑and‑jerk” dog trainers scoffed, and became even more adamant in their insistence that reliable, competitive training could only be accomplished with compulsion.

The debate quickly became reactionary. Both sides entrenched, and there appeared two groups that vociferously espoused pure forms of each method. Thus, inducive trainers said that they did not need force , while compulsive trainers insisted that they were not using force.

Then, as so often happens, it became evident that the conflict in theory was not as insurmountable as we thought and that, all along, the most consistently successful dog trainers were using a combination of both methods.

Nowadays, a seemingly obvious conclusion has been reached. We do not see induction and compulsion as separate, distinct and incompatible systems of training, but instead as parts of the same system. Induction and compulsion serve different purposes. They are each used at different stages in the dog’s development, and also at different stages in the teaching of any given exercise.

Inducive methods are used to introduce dogs to new skills and concepts (to teach). They are used to convey understanding to the animal. Furthermore, they produce better motivation for most tasks, and a better, more pleasing appearance in almost all tasks. They are used, above all, in training puppies, but they are also invaluable in dealing with sensitive adults.

Compulsion and force are used only when the dog has attained a precise understanding of the skill expected of it (to train), and only when it has established a habitual, lively pleasure in performing it. Compulsive methods are used to polish the dog’s performance and make it absolutely reliable.

However, the conversion from an inducive to a compulsive method is by no means inevitable. It is instead a function of the animal’s character. Some dogs are too soft and sensitive to support much force. Other dogs are so willing and talented that force is not really needed to polish the majority of their exercises. In the case of an animal like this, if it comprehends what it is that we want from it, then it happily and reliably does it. This dog therefore can and should be handled inducively all its life.

The proportions of compulsion versus induction in a training program are not solely a function of the dog’s stage in training or its character; they are also a function of the handler’s character. Some people are simply not comfortable using force in dog training, while others see it as the only way. It is perhaps best to view the inducive versus compulsive question as a continuum that runs from pure inducive to pure compulsive, with all trainers falling somewhere on that continuum according to their preferences. Quite simply, it is a question of temperament. For instance, of the two authors of this book, one regards the conversion to compulsion as a necessary and desirable development, while the other regards the conversion to compulsion as a last resort, the thing to be done when all inducive strategies have failed.

Дата добавления: 2015-05-08; просмотров: 3821;